By Rawle Lucas

Big Dent

The administration promised that by 2010 it would put a big dent in the housing problem which existed throughout Guyana at the end of the 20th century. These words appear to be an expression of good intent by the administration to tackle the poverty crisis in Guyana through improving the housing situation of its population. When the National Development Strategy (NDS) was first developed in 1996, the administration estimated that Guyana would require 5,200 housing units to be built every year for 10 years to ease overcrowding and to replace the deteriorating housing stock. While noting the problem, the administration did not commit itself to resolving it until 2000. After 10 years, the administration appears nowhere near breaking the back of the housing problem despite its promises and recent public announcements about the issue of 17,000 house lots and land titles, neither of which guarantees a roof over one’s head. Despite developing an intimate relationship with the financial institutions in Guyana, the housing crisis remains one of the more thorny issues of poverty since solving it involves confronting the issues of homelessness and overcrowding that affect about half of the Guyanese population.

Resolving the housing crisis also requires meeting the prerequisites of access to money through employment and through loans. The purchase of a house is a heavy long-term investment for which many individuals do not readily have the means. It often involves obtaining a mortgage, which is, borrowing money with an extended maturity period from a bank or financial institution to supplement the down-payment that an individual puts towards the acquisition of a house. Both the placement of a deposit and the acquisition of a mortgage often require the individual to have a stable and long-term stream of unencumbered income, usually a job or business income, free of discretionary debt. A housing crisis in Guyana therefore points to a deeper economic problem that goes beyond the housing market.

Permits

Where does the administration stand on the delivery of its promise of 10 years ago? One way to find out is to count the housing inventory. Such a task would require extensive and expansive travel all across the country and undertaking such an assignment would neither be feasible nor economical. Alternatively, it would make sense to count the number of permits issued by the Central Housing and Planning Authority for the construction of new homes. Housing starts do not necessarily mean completed houses, but the permits provide an indication of the number of houses that were expected to be completed within a specified timeframe. Once properly classified, the data make it easy also to determine which building activities were intended for housing. However, this type of information is not published by the Bureau of Statistics and is not readily available to the public.

Reliable Metric

The next most reliable metric to help assess the progress towards resolving the housing crisis is the number of mortgages issued for building construction. Like housing starts, mortgages do not mean completed construction. Everyone agrees that a house is an asset of value and presumably this is the reason the administration is doing everything to showcase its efforts in this area. There could be other motives, especially with elections around the corner. However, a mortgage involves a financial commitment between the borrower and the lender and it is reasonable to believe that the borrower would be motivated to convert the loan into an asset of value. Moreover, the obligation to repay the loan is a strong incentive for borrowers to erect a structure with the mortgage. While there will be a timing difference between the date of the loan and the date of completed construction, the number of mortgages issued can give a fair representation of the likely change in the housing supply. Like permits issued by the housing authority, mortgages do not tell, without some additional digging, if the construction is for a dwelling or a business. The mortgage data are easy to use since they are published by the Bureau of Statistics and are available to the public.

Aging Stock

When the NDS was initially completed in 1996, the administration had estimated that Guyana would need at least 5,200 units of housing per annum to replace the aging stock of houses and to accommodate the newly forming households. The mortgage data used to measure progress points to an unresolved housing crisis in Guyana. By 2000, the administration had fallen behind the stated goal by over 16,000 units. This is so even with the conservative view and belief that all mortgages issued by the financial institutions in Guyana were for housing construction. Since then the situation has worsened. By its own admission, the administration had issued a meager number of house lots between 2005 and 2009.

Shortfall

With an average of 1,471 houses being built annually from 2000 to 2009, the supply shortfall is estimated at over 37,000 units over 10 years when measured by the number of mortgages issued. Even if the focus was on newly formed households, the estimated shortfall would be over 10,000 units in the same time span. By 2002, the administration had estimated that households in Guyana were increasing by an average of 2,500 per annum. This meant that Guyana was falling behind by an additional 1,300 units annually. So, despite the photo opportunities and the chatter about the allocation of house lots, the administration is not even close to meeting the commitment that it made on housing in the NDS, based on the available data. It is not surprising that house rents have recorded steep increases over the years and the rent increase last year was as high as 18 percent.

Nature of Incentive

Part of the problem resides in the nature of the incentive programme designed to stimulate owner-occupied housing production. The incentives put in place by the administration favour those who supply financial capital and contractors involved in the construction business. Since 2005, the commercial banks have enjoyed special concessions that exempt money lent for mortgages from income taxes and the reserve requirements of the Central Bank. The housing programme of the administration is therefore good business for the commercial banks and it should come as no surprise to anyone that the banks eagerly embrace the administration’s “One-Stop-Shop” initiative. The banks are able to keep for themselves all the income that they earn from issuing mortgages for home construction. Contractors also enjoy reduced taxes on building materials. With the administration helping to stimulate demand through the land allocation programme, both the banks and building contractors have much to gain and to cheer about.

Job Creation

On the other hand, borrowers enjoy no special privileges, except those who are deemed low-income borrowers. The policy provides subsidies to low-income individuals. However, the strategy does not address the fundamental issue that the housing crisis reflects, that is, the lack of job creation. There are no incentives for rapid job creation that puts many Guyanese in a position to qualify for a mortgage and to have the ability to repay one. This issue is at the heart of the gap between the demand and supply of housing. Without the capacity to repay, Guyanese will be unable to obtain mortgages to buy their own homes. That is the case of many Guyanese who find themselves receiving house lots and do not have the ability to build houses on them. Consequently, the housing crisis will continue to worsen until the administration makes a serious effort at making job creation its number one priority.

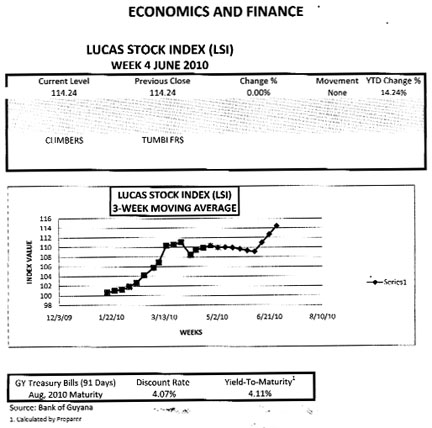

LUCAS STOCK INDEX

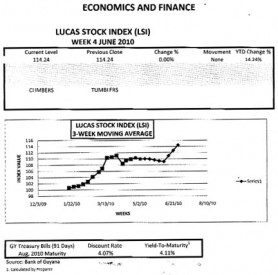

In week four of June 2010, the Lucas Stock Index (LSI) showed no change in the value of stocks traded on the Guyana Stock Exchange, even though the number of trades was larger than the previous week. As a consequence, the gain of the LSI remained at 114.24% for the year and three and a half times higher than the yield on the risk-free Treasuries that would mature in August 2010.