By Gaulbert Sutherland

Barefoot, four-year-old Sara and her sister, Varshanie, three, stare forlornly at their water-logged, garbage-strewn surroundings on the Best Village foreshore.

“We ain’t got nowhere to go, that’s why we come here,” their mother, Amanda Gouveia says. She knows that the perennially flooded, insect-infested flats amidst mangroves is no place to bring up her five children but reiterates that they have no place to relocate to. Other residents of Plastic City, a squatter settlement on the West Demerara with no electricity or potable water or any other service, say too that they cannot afford any place else. According to reports, Plastic City was so named because plastic was the main building material used in the original ‘houses’ there.

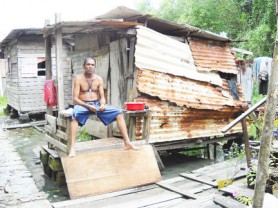

Susan Ramdass, 23, grew up in Plastic City and continues to live there with her husband and four children. She recalls that some time back Ministry of Housing officials visited, numbered each home and promised assistance with acquiring house lots but since then they have heard nothing. Other residents also recall a visit by Minister of Housing and Water Irfaan Ali but say nothing has happened since. Over a dozen families live in leaking board and zinc shacks on the edges of Plastic City while others live in sturdier houses at the front.

“We grow up small in here and we still living here,” Ramdass says. Like all the residents, the woman says if she is allocated a house lot elsewhere, she is willing to move. Plastic City, which floods during the high tides and never dries during the rainy season, is not healthy for children, she says. She points out that when the water rises, it floods the latrines. Her home is built with pieces of “crab bush wood”, wattles and covered with zinc. “None new brand material ain’t deh on,” she says.

Ramdass says her husband, Jaiveer Kumar Lall, a labourer, does not earn enough. “Just because people can’t do better mek people live here,” she says.

Rampattie Ramassar says the Housing Ministry had promised to assist with house lots. She says they had to fill up forms and send them in but have had no update so far. “I glad to move from here,” she says citing the flooding, mosquitoes and sandflies and the fact that they have to go a long way to fetch water for everyday use. Residents also collect rainwater.

Ramassar lives with her four children. She says she used to rent a house but can no longer afford this. She moved to Plastic City after she purchased a ‘house’ there. Ramassar, a vendor, says if a house lot is identified, she is willing to pay for it in instalments because she cannot afford to pay a lump sum.

Living in Plastic City was never meant to be permanent, she says. “We willing foh move if the people give we house lot cause the place is not nice for children and so.”

“If we coulda afford it, we nah woulda living here,” says Radica Ramdass, who lives with her husband and son in Plastic City. She says if they got a little help, they are willing to move immediately. “We ain’t want to live forever back here.”

Her sister, Samantha is constructing a new home close to Radica’s. The mother of three says she too cannot afford to go anywhere else. Shanta Ramdass echoes a similar story.

Another resident, Roxanne Mayers says they cannot afford the $112,000, they are expected to pay for a house lot. “They only promising us and ain’t doing nothing,” she adds.

Over the years and recently, the authorities have been urging Plastic City residents to move.

In March last year, Ali said that a risk assessment will be done in Plastic City and some persons may have to be relocated.

Meantime, Gouveia is also looking to construct a new home in Plastic City, moving out of the home two houses away where her parents died. As her daughters gaze at the numerous crabs scuttling across the mudflats, she adds that if she gets a house lot, she is ready to move.