I was born at Hague and spent the very early part of my life there, but in my teenage years the Martins family lived at New Road, Vreed-en-Hoop. We had no electricity, no running water, no telephone. People went to bed early, and so two young men who walked the road at night playing acoustic guitars stood out. The two guitarists were Joe and Jack Henry, and drawn by our mutual love of music, we became good friends. Joe and I, in particular, were like brothers; putagee and dougla, but brothers.

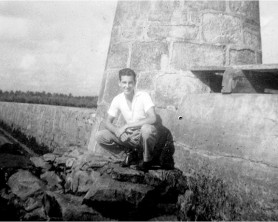

Our favourite liming spot was the seawall and the groyne that ran from it eastward into the sea. The Vreed-en-Hoop groyne was a formidable stone-and-concrete structure, about three feet wide and about five feet high, close to half a mile long, with a round tower in the middle, shaped like a huge bottle. I know no groyne in Guyana like it. At the eastern end, there was a greenheart tower with a navigation light at the top. We would sometimes climb to the platform at the top of the tower, play guitars, and shoot the breeze in the breeze.

Our favourite liming spot was the seawall and the groyne that ran from it eastward into the sea. The Vreed-en-Hoop groyne was a formidable stone-and-concrete structure, about three feet wide and about five feet high, close to half a mile long, with a round tower in the middle, shaped like a huge bottle. I know no groyne in Guyana like it. At the eastern end, there was a greenheart tower with a navigation light at the top. We would sometimes climb to the platform at the top of the tower, play guitars, and shoot the breeze in the breeze.

Germane to this story is that there was narrow fringe of mangrove (we call them cruda) trees close to the sea wall, but beyond that, where the groyne ran out into the river, it was basically seawater at high tide, and mudflat at low. The groyne was a unique place with a strong flavour of solitude. We spent many languorous hours out there, and I would also go there by myself in the daytime during the six months or so after Saints, when I couldn’t find a job. It was a quiet windswept place. Usually you were out there alone.

Fast forward now a bunch of years. Although I’m coming back to Guyana with Tradewinds, it’s usually a very compressed visit: fly in, play, fly out to play somewhere else; sometimes I wouldn’t even get to visit my aunts at Hague, so I never had enough time to check out the landscape in any detail.

And then, about a year ago, I was on the Stabroek Market wharf, looking across at Vreed-en-Hoop, and I was shocked. All I could see was mangrove bush: the groyne was no more; the wooden tower at the end, no more; the stone tower in the middle, no more; the concrete structure, gone. I could see the mangrove, green and lush, and a leaning remnant from the groyne in the sea, but there was nothing else. I was astonished.

And then an environmentally-aware lady set me straight: in fact, the groyne was still there; I couldn’t see it because it was now covered in deep bush. In the years since I had been there, the fringe of mangrove had spread out to the east along the mudflat creating a forest half a mile wide.

The groyne was still there; it had simply been enveloped by a forest. This was even more astonishing. What I knew as a youngster was a naked groyne with nothing growing on either side of it. What is there now at the edge of Vreed-en-Hoop is actually a dense mangrove forest with towering trees, many 20 feet high, holding the old concrete groyne in its belly. You can’t see it from afar – the foliage is too dense – but closer in there’s this narrow break in the bush, and the groyne, a horizontal backbone, virtually intact, slicing a tunnel through the forest.

Unless you knew the area from 20 years ago, it’s hard to believe what has happened there. Land, swampland, and dense mangrove forests, covering several hundred acres, have been spontaneously generated where there was nothing but mudflat.

It’s a stunning transformation. What has grown up there is a mangrove forest so dense that walking the groyne you sometimes cannot see the sky. Light often does not penetrate the foliage to your left and your right. Even the breeze is blocked out. Scores of crabs scurry away between the mangrove roots on either side, and young boys, ankle deep in mud, go after them with crocus bags.

Within sight of the Georgetown harbour, the Vreed-en-Hoop mangrove forest is an unheralded phenomenon.

The accompanying pictures may help to show it, but it is only when you clamber onto the surviving groyne and walk along it through the swampy forest, only then, knowing what it was 20 years ago, can you truly understand what has taken place there; that nature, working only with mangrove trees, has made acres of land where there was previously none.