Pearl Islands

Amerindians had been living in this part of South America for thousands of years before the initial wave of interlopers showed their faces. It was the Spanish explorer Alonso de Ojeda who in company with Juan de la Cosa was the first European to see our coast in 1499, and it was no doubt his caravels which were the first European boats our Amerindians ever laid eyes on.

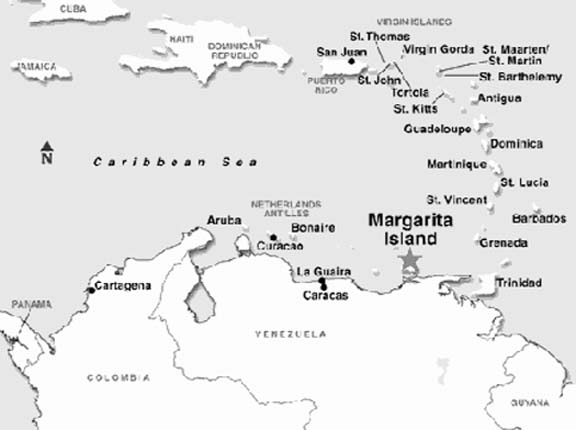

But the Spaniards were not interested in a muddy shoreline which had a habit of disappearing beneath the waves at high tide, and on this inaugural foray into our neighbourhood, they simply sailed on past. Neither did they have any interest in settling later; their eyes were fixed on a more lucrative prize. In this part of the world wealth in European terms was represented by the Pearl Islands off the coast of Venezuela; in particular Cubagua, Margarita and Coche.

These were, however, barren places subject to water shortages, and the Spaniards who established themselves there soon found they were obliged to import most of their food supplies. The conquistadors enslaved the indigenous population of the islands, and if they did not die from disease or maltreatment, the pearl fishers certainly succumbed to the consequences of the incessant diving the Spaniards demanded of them. The peoples of the mainland behind the islands fared no better, being sourced for labour as the island inhabitants diminished in number and finally were wiped out. So the Spanish had to cast further afield for providers of foodstuffs.

These were, however, barren places subject to water shortages, and the Spaniards who established themselves there soon found they were obliged to import most of their food supplies. The conquistadors enslaved the indigenous population of the islands, and if they did not die from disease or maltreatment, the pearl fishers certainly succumbed to the consequences of the incessant diving the Spaniards demanded of them. The peoples of the mainland behind the islands fared no better, being sourced for labour as the island inhabitants diminished in number and finally were wiped out. So the Spanish had to cast further afield for providers of foodstuffs.

At first they relied on the Arawaks of the Orinoco River and Trinidad to provision them, although in the early years it was a relationship occasionally interrupted by Spanish excesses in the Orinoco. However, in 1545, a more stable arrangement began, after a fugitive Morisco slave who had lived among the Arawaks for twelve years, decided to return to Margarita and Cubagua. He reappeared there in the company of 50 Arawak piragas.

Cassava bread for export

By the middle of the sixteenth century, Arawaks from the Essequibo and more

westerly Guyanese rivers were also provisioning the Spaniards in the Pearl Islands, and the Arawaks in general are credited with saving the inhabitants of Cubagua from starvation on at least one occasion by bringing in six hundred loads of cassava bread and other food.

Exactly how our Arawaks became provision merchants for the Spanish in Cubagua, is not really known, but the volume of goods they transported in their sea-going piragas to the Pearl Islands clearly impressed Spanish contemporaries. According to one early governor in the islands, the Arawak convoys normally came annually and sometimes stayed for as long as a year.

In the second half of the sixteenth century, the Arawak relationship with the Spaniards in the Pearl Islands was quite unlike that of their indigenous counterparts in what is now Venezuela. It seems to have been a straightforward trading relationship, and the Arawaks were protected from enslavement from as early as 1520.

As far as Guyana is concerned, it appears that the Spaniards never managed to establish themselves here and force the local people to plant for them, so as a consequence they were left totally dependent on their Arawak suppliers for their survival. This gave the latter a special status, more especially as they were the ones who paddled up the coast to Cubagua with their provisions, not the Spaniards who came to them.

The Spaniards did draw up two schemes to convert the Arawaks, including those along our coast. This would have been a prelude, no doubt, to some form of occupation, but it never came to fruition. There is also a story from the seventeenth century that the Spanish attempted to gain a foothold on our coast by building a fortification at the mouth of the Barima. This too, it was said, came to naught since it was wiped out by the Caribs in 1530.

The provisioning demands of the Europeans on Cubagua must have been fairly substantial, and it is unlikely that the Essequibo and other Arawaks amassed the food supplies and other things for export entirely from their own resources. All the indigenous peoples of this continent were experienced traders, exchanging a wide variety of products, sometimes over vast distances. The sea-going piragas used by the Arawaks, for example, had most likely been made by the Warraus, who were the boat-builders of north-eastern South America. And once they had got the measure of the European greed for gold, the Arawaks would bring the Spaniards any items of worked gold which had been traded down the river systems into lowland Guiana from the Colombian highlands. The Spaniards were quick to note these were not pure gold, but the alloy tumbaga, a sure indication of their origin.

They would also sometimes bring slaves, although this was probably on a somewhat limited scale.

What the Arawaks brought to the other tribes in exchange for their cassava bread, provisions, hammocks and whatever else, was iron goods in particular. For cultures which had laboured with stone implements for so long, these were a revelation, and it made the Arawaks the distribution agents par excellence of their day. Spanish-made products no doubt penetrated into the heart of Amazonia, traded from community to community.

Nothing, however, lasts for ever. The pearl fisheries eventually became worked out, and the provisioning needs of the Spaniards in that area began to diminish somewhat. The relationship was still maintained nevertheless, until the end of the sixteenth century. But by that time a new Spanish interloper had made his appearance in the region, and he was altogether of a different temper. And the Amerindians were to find too that there were other Europeans stalking their coasts who did not belong to the Spanish ‘tribe.’

(To be continued)