Mining for gold and diamonds is a major industry in Guyana. In spite of a written history of this pursuit going back to Dutch times, not to mention what took place among Amerindians before that and in pre-history, it has not brought the country any significant wealth. It has, however, brought a history of extended conflict and some tragedy. In recent times there have been renewed ventures – some of which were short-lived – immigration, new economic activities, environmental issues, crime, major controversies and an extraordinary store of literature and other cultural treasures.

Mining for gold and diamonds is a major industry in Guyana. In spite of a written history of this pursuit going back to Dutch times, not to mention what took place among Amerindians before that and in pre-history, it has not brought the country any significant wealth. It has, however, brought a history of extended conflict and some tragedy. In recent times there have been renewed ventures – some of which were short-lived – immigration, new economic activities, environmental issues, crime, major controversies and an extraordinary store of literature and other cultural treasures.

While gold-mining makes a substantial annual economic contribution, what this industry does to strengthen Guyana’s GDP always seems less than it ought to be. It has still not made Guyana a rich country. In recent times mineral mining has been in the news and attracted attention for regrettable reasons. These include incursions of undocumented miners, illegal activity across porous borders, murders and other crimes in under-policed interior locations, environmental concerns because of destructive mining methods and miners’ reactions to the imposition of regulations. The recent global interest in conservation has had direct developments in Guyana because of this great natural resource that it possesses.

However, what is not in dispute is the immeasurable wealth that the search for and pursuit of gold has given to the nation. The unfathomed reservoir of literature, oral literature, folklore, folk tales, folk songs, stories and jokes, myth, legend and history is priceless. In its Guianese incarnation it all begins with a fabled city of gold called Manoa, hidden somewhere in the Rupununi on a lake called Parime. Manoa was ruled by a gilded monarch known as El Dorado (the Golden One) and the local myth has inspired literature, poetry, drama, fiction and imagination without boundaries.

However, what is not in dispute is the immeasurable wealth that the search for and pursuit of gold has given to the nation. The unfathomed reservoir of literature, oral literature, folklore, folk tales, folk songs, stories and jokes, myth, legend and history is priceless. In its Guianese incarnation it all begins with a fabled city of gold called Manoa, hidden somewhere in the Rupununi on a lake called Parime. Manoa was ruled by a gilded monarch known as El Dorado (the Golden One) and the local myth has inspired literature, poetry, drama, fiction and imagination without boundaries.

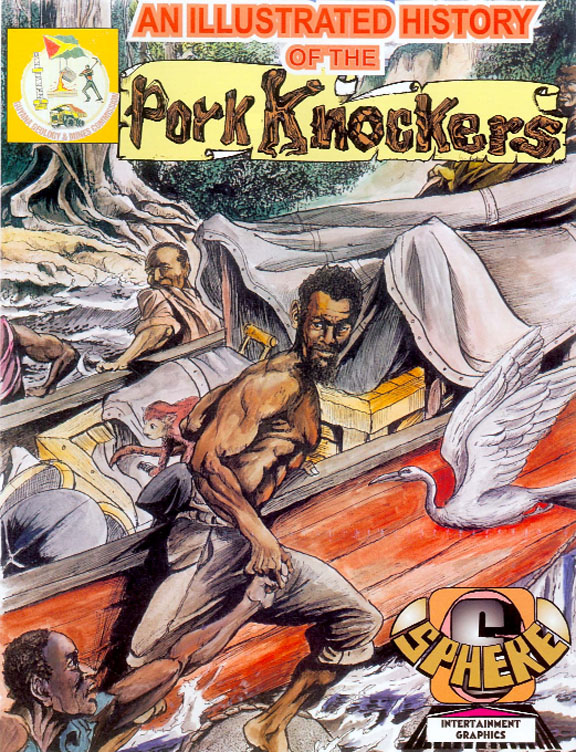

The very latest in this long and noble line of publications is An Illustrated History of the Pork Knockers (2010) by Barrington Braithwaite. This is a novel publication of a different type; a fully illustrated text in comic book form. It is a thorough documentary of a particular brand of gold mining known to Guyana and carried out by a legendary breed of adventurous and courageous workers called ‘pork-knockers.’ This industry is conducted by men from coastal villages or the city who venture into the vast interior either individually or in groups, to brave the horrors of a hostile environment to dig for gold and diamonds.

They have traditionally used rudimentary methods, though that has changed somewhat in recent times, and although they often reap success and legendary wealth, it is a life of hardship and economic uncertainty.

There are different versions of the origin of the name ‘pork knockers,’ but one of the popular is that it comes from the fact that because they spend lengthy periods in the bush their staple diet is dried, cured pork. Braithwaite provides another variant – “poke knockers” and provides an explanation. “As for ‘poke,’ that related to the poking of the prospectors in the search for mineral veins. Even the way it is written, like all forms in the oral tradition, is not standard. It has appeared as pork-knockers and even porkknockers, but Braithwaite sticks to the use of two separate words. Again, true to the oral traditions, these men and their stories have generated a corpus of tales and even a mythology. They have found their way into folklore and because of their existence “in the bush” their lore is associated with other folk material and traditions that have come out of the traditions and superstitious beliefs of that environment.

Before Braithwaite, the pork knockers inspired the imagination of Guyanese writers who have produced a number of fictionalised creations. These include the novel Black Midas by Jan Carew, an account of the legend of famous pork knocker Ocean Shark.

Although Shark is mentioned by Braithwaite, Carew’s novel highlights a side of pork knocking that he largely avoids – that is the dominant picture of the itinerant prospector as a reveller, an ostentatious spendrift for whom wealth is ephemeral. Carew’s interest is fiction; Braithwaite dignifies the industry of pork knocking, giving it an honourable place in the nation as the story of unprivileged men who have shown industry and bravery against a history of obstruction and colonial hostility. As he points out, the weak side of pork knocking is well played up; he wants also to show that there was achievement.

Other works are in drama: a play Porkk-nockers by Sheik Sadeek and another Makantali by Harold Bascom. The latter is a major Guyanese drama by one of the country’s best playwrights. Bascom gets into the life and spirit of the people in the industry, ennobling it with a plot involving a prospector who has enough sense, guided by the spirit of a past pork knocker, to learn and influence others away from the stereotype wayward and tragic life. Bascom takes his concept from a traditional song which is also treated in Braithwaite’s account as the story of Bakandali, a variant of Makantali, who was one of the great legends of the 1920s and ’30s. Its source is one of the many songs about these adventurers with the lyrics “Mack an Tally money done in de country / Mack an Tally money done ay” but Braithwaite says “some folk singers still maintain Bakandali.” Lynette Dolphin’s collection One Hundred Folk Songs of Guyana contains a number of these songs, which are also treated by Braithwaite. These include ‘Maanin, Neighbour, Maanin’ which touches subtly on interpersonal conflicts between villagers, on insincerity and what Braithwaite describes as “the extravagances of newly found bush money “ and “its humbling and neutralizing reality when this wealth is lost.” It also mentions the Kurupung Landing, one of the most famous locations in interior mining and legends. There is also Itanami, the folk song whose lyrics capture the awe and fear surrounding the dangerous rapids named Itanami up the Essequibo. There is another song not mentioned by Braithwaite, composed in the mode of the traditional about ‘Going Up the Potaro.’ Derek Bernard wrote a short story called Going Home, whose tone is as moving as that of the song.

An Illustrated History of the Pork Knockers gives credit to The Guyana Geology and Mines Commission which seems to be, at least in part, publishers of the book. The credits also include computer formatting by Roderick Harry and a historical review by Hazel Simpson. It is edited by Audreyanna Thomas. This is overall an excellent piece of work which covers many aspects of pork knocking. Its treatment is as thorough as the drawings which illustrate it. Braithwaite is an accomplished artist, a master of anatomy, drawing and colour. He is also a very keen researcher whose period sketches can be fully relied upon because of the accuracy of the researched costuming and architecture. Some of the stories are half-told, there are omissions, the actual written text needed to have been more closely proof-read; the author is at times selective and politically correct in what seems to be his preoccupation with presenting pork knockers as respectable industrial workers. Yet he is honest in the occasional mention of unfavourable elements such as the need in the 1950s for “proper regulations and control of the pork knocker who was getting slightly out of control.” Note his use of “slightly” as his very sympathetic treatment glosses over many of the problems and failings.

Yet the author’s intentions are commendable. He avoids derogatory terms such as “bush whore” and uses the word “prostitutes” only once in his several references to “women of pleasure derogatorily defined as bush women.” He gives them respect and dignity with descriptions which in two places invoke slight humour. For the lonely pork knockers, physically attractive “feminine company was a humane escape,” especially “women that did not require the patience of civilised courtship.” Then, while discouraging the rumoured ‘scampishness’ of some of these women, he mentions “a particular woman named ‘the maid of Clantoy,’ who did lure many a pork knocker like the sirens of myth.”

Braithwaite is therefore a man of great delicacy in his documentation of women in this publication. He takes pains to point out that many women also made famous names for themselves and the industry in trade, mining, prospecting and the management of business. He pays them tribute. Apart from those he includes the history of West Indian islanders such as the St Lucians who joined the hunt for gold.

However, he makes no mention of Mahdia or the British Guiana Consolidated Gold mining operation which brought many of them to BG in the 1930s. But his book documents almost everything else, and carries sections on the relevance of Emancipation, the rise of the individual pork knocker, folk songs, legendary figures, folklore and the supernatural, the dangerous animals, Women of the Gold Bush, The Islanders, the History of Bartica Grove the Capital of the Pork Knockers, Water Dogging, Jokes Omens and Dreams.

One of the most impressive features of the publication is its concept. Braithwaite’s research and thinking show depth as he sees this history as beginning with the myth of El Dorado and the history of Spaniards who pursued it ruthlessly, as well as the story of Sir Walter Ralegh. All these are well researched including the continuing quest for gold among the Dutch who first set up mining companies, followed by the English. All of this provides background to the rise of the small pork knockers while laying a basis for the hardships laid out against them right through history. “Their name defines our knocking at the door of fortune of El Dorado’s kingdom.” Braithwaite sees their history as one of triumph and achievement.

The Illustrated History of the Pork Knockers is very important material excellently researched and presented, and takes a prominent place among any work done on this subject. Barrington Braithwaite gives credit to many who contributed to the eventual appearance of a publication that he says first began in ideas twenty years ago. These include the National Museum and a number of publications which he acknowledges. He expresses gratitude to the Geology and Mines Commission and its then Commissioner Robeson Benn as well as current Acting Commissioner William Woolford whom he approached in 2005 and “was overwhelmed by their enthusiasm.”

Braithwaite’s work over the years has resulted in many publications including Shadow of the Jaguar, a comic book Trilogy which was turned into a stage play in 1992; Folk and Culture, a magazine of cultural traditions in 1995, a mystic spiritual character called The Elder, published in newspaper comic strip series, and another comic book The Legend of the Silk Cotton Tree, whose story and concept were used to produce Guyana’s dramatic play for Carifesta 2008. He is a prolific illustrator and researcher and both those strengths have come together once again to produce this important work about the history of pork knocking which is for its author, a work of triumph and achievement.

It is very highly recommended.