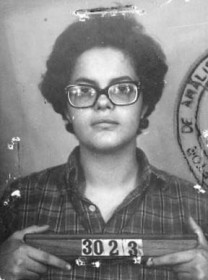

Not every president has a police mug shot, but it’s not so surprising in Latin America. This special report sheds new light on Dilma Rousseff, a former guerrilla leader who is likely to be elected the booming country’s next president in October. She spent nearly three years in jail in the early 1970s and was tortured by her military captors. She’s come a long way since then.

By Brian Winter

and Natuza Nery

JUIZ DE FORA, Brazil (Reuters) – Here’s some advice for anyone who meets Dilma Rousseff (aka “Stella.”)

First, speak quickly. And second, if you’re looking to ingratiate yourself, it’s probably not a good idea to suggest that major reforms are needed for Brazil to retain its title as one of the world’s fastest-growing emerging economies.

In an interview with Reuters, she flatly dismissed the need for big budget cuts or changes to some of the world’s most restrictive labour laws. Asked if it was possible for Brazil to keep growing at a 7 per cent annual pace without such reforms, Rousseff shook her head, smiled, and interrupted the question.

“Is Brazil growing (that quickly) now?” she asked sharply.

Well, yes, but some economists say…

“But is it growing?”

“Yes.”

“Well, then, it’s possible,” she concluded.

The message was clear, and it was reinforced in interviews with about a dozen of Rousseff’s top advisers: for better or worse, the 62-year-old former guerrilla leader, who has evolved over time into a highly pragmatic career civil servant, does not plan major changes to Brazil’s economic policies if she is elected.

Rousseff’s wager is that she will be able to create millions of jobs, improve Brazil’s woeful infrastructure and schools, and harness its newfound oil wealth without deviating substantially from the mix of social welfare plans and market-friendly policies that have made her former boss, current President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, wildly popular both at home and on Wall Street.

Lula, for his part, has left little doubt that he expects his chosen successor to hew closely to his policies when he leaves office on January 1. As he told a crowd in August: “If I see something wrong, I’m going to call my president and say look, there’s a problem here. You can take care of it, my child, because I wasn’t able to.”

The primary risk with Rousseff seems to be a status-quo presidency that results in economic stagnation. Given her lack of appetite for major reforms, some economists fear that Brazil’s notoriously high costs of doing business could soon drag the country back to its trend growth level of years past — around 3 per cent — and thus cause the country to fall behind its high-flying peers in the so-called BRIC group of big emerging markets: Russia, India and China.

Rousseff’s relative lack of charisma or executive experience could also leave her government vulnerable in the event of an unexpected external or internal crisis. Her potentially volatile coalition of political parties is another question mark, as is the bout of moderate cancer that she suffered, and completely overcame, in 2009.

Yet, like their future boss, many potential officials in a Rousseff government seem unconcerned that Brazil’s run of prosperity could end any time soon.

“We’re going to do what we can,” said Fernando Pimentel, a senatorial candidate and adviser to Rousseff’s campaign who has known her since the 1960s, when as teenagers they were both involved in the armed resistance to Brazil’s dictatorship.

“But there are certain areas where you can just turn on the automatic pilot,” Pimentel added, citing the finance ministry as an example. “Brazil is in a stage of tremendous growth.”

From jail and torture to public office

Rousseff has downplayed the importance of her activist youth, which saw her imprisoned for nearly three years and tortured by her military captors. But the truth is that, while the era did not define her, it is critical to understanding her rise in Brazilian politics.

The daughter of a well-to-do Bulgarian immigrant who fled political oppression in his own country, Rousseff joined a radical leftist resistance group known as the Colina shortly after entering the economics programme at the Federal University of Minas Gerais.

The leftist groups that proliferated throughout Brazil never engaged in large-scale combat or posed a serious threat to the military government. Instead, they consisted primarily of loosely affiliated cells in urban areas that robbed banks, set off bombs and kidnapped and killed political figures.

Rousseff’s second husband, Carlos Araujo, was a fellow dissident. He said that her responsibilities consisted primarily of “coordinating” the actions of various cells. As the military cracked down, both went on the run for months at a time and assumed aliases — including, in her case, “Stella.”

Rousseff herself “never picked up a gun,” Araujo said. “And she never fired a shot.”

Husband and wife were both soon captured. Rousseff suffered “extremely cruel” torture while in prison, Pimentel said, including repeated electric shocks.

“It pushed her to the edge,” Pimentel said.

Even prior to her imprisonment, though, Rousseff had begun displaying the pragmatic streak that would come to define her career. Pimentel said she “was one of the first among us to realize” that the guerrillas were outgunned and badly organized, and would not succeed in toppling the military.

Indeed, upon her release from jail in 1973, Rousseff never really looked back. She resumed her studies in economics and completely gave up hard-line resistance, Araujo said.

“Just as we got into that world quickly, we exited it quickly too,” he said. The two are now divorced, but they remain close and the car in the driveway of Araujo’s house in Porto Alegre has a giant Dilma sticker on the rear window.

On the national stage, a crisis waits

When she was finally given an opportunity on the national stage, Rousseff seized it — and began to reveal her true colours as a leader.

The year was 2003, and Lula had just been elected president on his fourth try. The former metalworkers’ union leader, who in previous campaigns had advocated defaulting on Brazil’s debt and nationalizing key industries, was under intense pressure to demonstrate to panicked financial markets that he would not undertake radical changes as president.

Eager to calm investors before the financial system fell apart, Lula reached into a shallow pool of officials from the moderate wing of his Workers’ Party to staff critical posts in his government. That included Rousseff, who had defected only three years prior from a different leftist party based in Rio Grande do Sul.

Lula put her in charge of the energy ministry, where a crisis awaited.

Brazil was still reeling from national electricity shortages, the consequence of a drought that left Brazil’s hydroelectric dams depleted, but also decades of underinvestment in more diverse energy sources. The result was widespread rationing that shaved more than a percentage point off economic growth in 2001.

Rousseff’s task was to lead a “complete overhaul” of the sector to prevent it from happening again, said Mauricio Tolmasquim, her former No. 2 at the energy ministry.

A working group of ministry officials gathered. Tolmasquim said that some from the party’s more radical wing advocated a partial reversal of the free-market reforms of the energy sector in the 1990s, which would have restored the former state-run electricity monopoly Eletrobras to a more prominent role.

In the end, Tolmasquim’s more moderate proposal prevailed: a “Dutch auction” system in which private-sector companies bid for projects based on how low a rate they could provide to Brazilian consumers. It also provided a legal framework that guaranteed their investments over the long term.

Lula’s administration has seen Brazil’s electrical capacity expand by about 4.4 percent a year, up from 3.9 percent a year in the previous government, according to official data. Blackouts are no longer a major issue, although Brazil’s electricity rates remain among the world’s highest.

Prosperity now, but there may be trouble ahead

As for just how she made her unlikely leap to front-running presidential candidate… well, even Rousseff admits to being a little hazy on that one.

She says that Lula began by “joking around” about a possible presidential run — “the only way that someone who is not thinking about becoming a candidate will get used to the idea,” she says.

To this day, Lula has never formally asked her to run, Rousseff says. “It was spontaneous, natural,” she said. “And over time, I just kind of became a candidate.”

There’s another version to the story. It’s unlikely that Rousseff would have been Lula’s chosen successor if not for multiple corruption scandals during his administration that forced more obvious candidates, namely former cabinet chief Jose Dirceu and Palocci, to resign in 2005 and 2006, respectively.

“It was like she won the lottery,” said Collares, the former state governor.

Rousseff began the campaign as an enigma even within some political circles in Brasilia. Her name recognition among voters registered in the single digits, and the nomination did not go over well among some in the Workers’ Party who wanted a better-known, more experienced candidate.

That helps explain why, from day one, she has staked her candidacy on a message of total continuity of Lula’s policies, appearing by his side at rallies and on TV as often as possible.

It has been an effective strategy. Under Lula’s mix of responsible fiscal management and cash transfer programmes to Brazil’s poorest, more than 20 million Brazilians have escaped poverty since he took office. In a country that was long defined by its massive gap between rich and poor, inequality has fallen and a newly empowered lower-middle class has been snapping up cars, homes and TVs in record numbers.

Lula has been, and will remain, a hard act to follow. At a joint rally last month in Osasco, an industrial suburb of Sao Paulo, Rousseff gave an awkward, at times rambling catalog of Lula’s accomplishments. She then promised to be “the mother of all Brazilians” and concluded her speech by pledging, at full-throated roar, that “this will be the election that dignifies the women of our country!”

The crowd clapped politely, as if they were attending a golf tournament. Lula then bounded on stage. The crowd burst into frantic cheering and chanting as music blared and confetti fell. With the flair of an experienced performer, Lula waited for the din to die down before grabbing the microphone, leaning into the audience and flashing a huge grin.

“Comrades…” he began. And the crowd went wild again.

The difference in styles has a serious side that goes to the heart of the limitations that Rousseff may face as president: if Lula, with his 75 percent approval rating and massive street cred with Brazil’s poor, couldn’t get contentious legislation such as a tax reform through Congress during eight years in office — then how can she?

Franklin Martins, Lula’s communications strategist and a close adviser to Rousseff, indicated that she is betting on responsible macroeconomic management policies that will bring down Brazil’s debt-to-gross domestic product ratio from its already low level of 41.7 percent.

That, in turn, should bring interest rates down from their current level of 10.75 percent, among the world’s highest. Martins pointed out that each full percentage point drop in interest rates generates about $9 billion in fiscal savings on Brazil’s debt payments. “That’s an entire Bolsa Familia,” he said, naming Lula’s social programme that sends cash transfers to poor families.

Martins says he’s sure that Rousseff will forge her own identity as president. “Anybody who says she’ll be an automatic pilot doesn’t know Dilma,” he said, laughing.

His other prediction — that Rousseff would quickly grow into the role of president, just as she has others throughout her career — is also showing signs of coming true.

At the rally in Juiz de Fora, Rousseff looked much more comfortable than she had at the Osasco speech, working the crowd into a frenzy by singing Lula’s praises.

She said a new spate of corruption accusations that have shaken her party were just cynical scare tactics whipped up by the opposition — much like predictions that the economy would collapse if Lula was elected in 2002, she said.

“Was there chaos?” she asked the crowd.

“Nooooooo!” they yelled back.

“Did Brazil grow?”

“Yessssss!”

“Did (Lula) create 10 million jobs?” she asked. But before the audience could shout a reply, she yelled one of her own into the microphone: “Nooooo! He created 14 million jobs!”

Many in the crowd laughed.

Lula lingered backstage for part of the night, watching Rousseff work the crowd.

Asked why he never actually asked Rousseff to run, Lula thought for a moment. “Because it worked out,” he said with a smile and a shrug. And then he bounded on stage, ready to push his chosen successor one step closer to power.