Conclusion

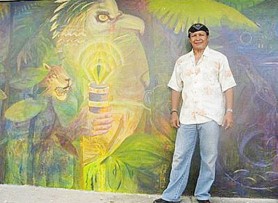

Interestingly, although Oswald Hussein is not an intuitive artist, this kind of atavistic spirituality is what lies behind the striking force of his work. He was the first of the Amerindian sculptors to put spirits into the forest and animals, producing sculpture which is alive with the Arawak psyche. More than any of the others Hussein’s work startles with the fearful and the grotesque because of this close relationship he feels with the spirits of the forest. This personal conviction lends his work a defining quality of Amerindian art.

Hussein goes on to declare “I like thunder and lightning. I use nature as something that gives strength.” Before he could create those works depicting thunder and the house of the jaguar, “I had to find myself first. I believe in what I am doing.” He relates to the environment and “live[s] directly with nature. I feel I could turn into something.”

Hussein goes on to declare “I like thunder and lightning. I use nature as something that gives strength.” Before he could create those works depicting thunder and the house of the jaguar, “I had to find myself first. I believe in what I am doing.” He relates to the environment and “live[s] directly with nature. I feel I could turn into something.”

Unlike Hussein, Winslow Craig does not feel that personal closeness to his native environment, although he has never been divorced from it. He is indeed influenced by the environment. “I was born in the bush, grew up in the bush” and his work reflects his early life. But he is not immersed in mythology and legends, and feels that he uses them only superficially. What is more important to Craig is that his work “reflects all humanity.” His work “reflects all of who I am. I am a mixture, I am Amer-indian, but my work does not reflect me as an Amerindian.”

That declaration is both borne out and not supported by Craig’s art. His Strength of the

Harpy: Vision and Claw, Hunter’s Visage and Embrace are very much within the general Amerindian preoccupations. But for the most part those spiritual and traditional elements tend to give way to a certain universality. His style is more highly polished, more classical and much more realistic than Hussein’s. He seems to strive after a studied, dispassionate excellence. When he moves off into working in metal, a craft he developed in New Zealand, what is definitely reflected is his universal interest.

Yet an important factor in Craig is his preoccupation with social issues and the depiction of social realities, particularly his interest in “dark situations.” Artists, he believes, need to look at the realities that are placed before them. Craig’s importance then, is the high place he has earned in Guyanese art and his national achievements as a sculptor of Amerindian extraction.

As a kind of a balance between Craig and Hussein, yet much too important and far too accomplished to be looked at in that way, George Simon’s interests are as wide as the cultures of the world and as deep as his Amerindian identity. He has paid attention to his native background; he has researched Amerindian mythology and spirituality and at one time had a personal interest in shamanism, but has developed a serious interest in “the myths, religion and culture of others”. This is represented by his tendency of late to show mixtures and mergers in his paintings. For example, he paints the Haitian goddess Simbi in a Pakaraima savannah setting.

In his latest work, and he has been extremely prolific in 2009 and 2010, he seems unable to confine himself to a single theme or a single culture in any one painting. In the Homage to Wilson Harris that he produced together with colleague Philbert Gajadhar and student Anil Roberts, he enters an intertextual engagement with Harris’s novel. But the work is steeped in Amerindian motifs which are blended with details from the novel. One of the motifs is “eyes.” This is linked to the hawk or eagle eyes of Kanaima, the eyes of the jaguar and the notion that the forest has eyes. There are several eyes in the peacock’s tail.

His preoccupation with the jaguar allows him to explore a very Amer-indian subject because of that animal’s associations with Kanaima, with the hinterland environment and with myth. His painting Golden Jaguar Spirit (2010) sees the jaguar as “a shamanistic animal” with attributes of spirituality. The marks on the body of the jaguar are eyes, but they are also petroglyphs as well as the leaves of the forest. Here he alludes to the changing forms as from kanaima to animal, as well as the merging and the oneness among animal, forest, spirit and man.

He explores the female figure in his “transformations,” mixing cultures, religions and goddesses, moving among Voodu, Hinduism, African and Amerindian goddesses. Simon also has a keen interest in the serpent and its importance in his own culture, but also brings in the flying serpent-dragon of the Chinese, the mythical Mexican bird-serpent and the female energy in the camoudi from which the Caribs descended in one of the myths.

Simon is decidedly too original and innovative to be typical of anything, but he very eloquently demonstrates some of the most exciting developments in Guyanese Amerindian art. More than that, he is a leader in charting its directions.