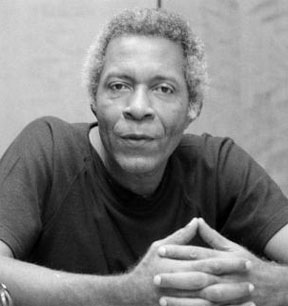

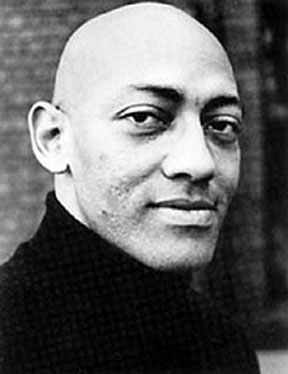

The revival of Trevor Rhone’s powerful drama Old Story Time by the Theatre Guild allows a timely new focus on this important Caribbean classic. This most recent production of the play was directed by foremost Guyanese director/actor Ron Robinson who has directed other Rhone plays before, and was playing the lead role of Pa Ben for the second time in his career. It was the second major Caribbean drama staged by the Guild in the two years since its rebirth, having done Moon on a Rainbow Shawl under the same director in 2009. While this production of the play will be focused in a subsequent discussion, the staging of it provides an opportunity for highlighting Rhone and his important work in Old Story Time. The play, rather than the Guild’s production, is the subject here.

Rhone, as a major Caribbean dramatist, has been very important in the development of modern Caribbean drama. He has contributed to the shape and state of contemporary Jamaican theatre, and it was this contribution that critic Mervyn Morris had in mind when he wrote in an introduction to Rhone’s plays, “Theatre in Jamaica has a long history; but, on the evidence available, Jamaican theatre is young.” It was only in the very recent period after three centuries of theatrical activities in the country that an identifiably Jamaican theatre emerged on the formal stage, and Rhone’s work in the 1970s helped to define it.

Rhone, as a major Caribbean dramatist, has been very important in the development of modern Caribbean drama. He has contributed to the shape and state of contemporary Jamaican theatre, and it was this contribution that critic Mervyn Morris had in mind when he wrote in an introduction to Rhone’s plays, “Theatre in Jamaica has a long history; but, on the evidence available, Jamaican theatre is young.” It was only in the very recent period after three centuries of theatrical activities in the country that an identifiably Jamaican theatre emerged on the formal stage, and Rhone’s work in the 1970s helped to define it.

Working with director Yvonne Jones-Brewster, Rhone founded the famous Barn Theatre in Kingston, and in that space, he proceeded further in collaboration with fellow dramatist Dennis Scott to shape and influence the rise of professional theatre in the region. This developed out of the plays he wrote during that time, which were directed at the Barn by Scott. They were a part of the rise of popular theatre, but drove the blend of popular material with important social issues and commercial production to develop the region’s professional theatre. Actors began to develop paid careers on stage (even if most of them had to do it part-time). It is, of course, remembered that Derek Walcott had been working with his Trinidad Theatre Workshop at the same time and achieving similar gains, but there were important differences between Walcott’s preoccupations and what was taking shape in Kingston.

Rhone became known across the Caribbean for humour, because of the great success of the two most popular plays of his that Scott directed, that were a part of this development. Smile Orange and School’s Out are hilarious and in demand for that reason, but they are excellent examples of how Rhone used satire to comment on serious issues confronting the tourist industry and the education system in secondary schools.

Old Story Time is not a satire, but it achieves much the same success in its treatment of other social issues and its thorough use of Caribbean drama. Rhone created and first performed it under his own direction in Nassau, Bahamas in 1979 with Bahamian lawyer Winston Saunders creating the role of Pa Ben. With the writer/director working closely with Saunders as collaborator, Pa Ben developed from a mere narrator telling the story from a remote distance, to an involved character who is able to tell the story while being a participant in it. Pa Ben achieves the role of lead character, story-teller, choric commentator and effective bridge linking parts of a story that evolved over a period of some thirty years.

It is a play about self-contempt. The tale told by Pa Ben begins in colonial times and confronts issues arising out of the social and political effects of a colonial society beset by factors of race, colour, class, exploitation and prejudice. These are complicated by hatred, ill-will and vengeance, and the consequences of characters turning to obeah to right perceived wrongs. What results involves strained personal relations and near tragedy which is only averted when the characters turn to the strength of human bonding, love and forgiveness as forces to exorcise the ills.

The plot revolves around a black market vendor in a country village who is determined that her son should educate himself for upward mobility out of poverty and the working class. But for her this advancement also means renouncing blackness and marrying into the white or light-skinned (brown) middle class. She beats this into him as he grows up. He is bright and indeed succeeds, becoming a Doctor of Economics. But he never forgives his mother for her past hounding of him which caused him unforgettable humiliation at school. She also is sorely disappointed because he marries a black girl, and this ill-will leads her to invoke obeah against her daughter-in-law, which leads to the complex conflicts in the play.

This heroine Miss Aggie, suffers from self-contempt, which in the context of the play, is a colonial condition. There are also indications of an undeveloped and unprogressive country village and the dominance in the society of a white and coloured bourgeoisie which practises racial prejudice and all forms of exploitation. Miss Aggie’s son has justifiable contempt for them, but also harbours an obsession with vengeance against the white villains who humiliated him in school and a grudge against his mother whom he blames for having caused it. He despises her rustic countrified behaviour, her distrust of blacks and her worship of the coloured bourgeoisie.

Rhone presents all of these in the play as social and personal ills resulting from the past colonial condition, the hangover from those times that still persists in persons in the present, and as personal angsts which bother some persons today. They are all ills and afflictions which cause discord and strain personal relations. They are conditions which need to be purged, to be exorcised from the systems of both the humans and the society.

Rhone’s techniques for communicating these are interesting and important. He shows links between the past and the present. The story told by Pa Ben is an old story that has its genesis in events that took place more than thirty years ago, but have caused developments which plague the characters in the present. He uses the story-teller and the Caribbean story-telling tradition as a device in the theatre to bridge this gap. Pa Ben can move easily in his narration across time. He uses the members of his audience as actors who play the roles of the people in the story and in this way controls a very fluid situation in which he can enact past and present scenes as he tells the story. Rhone also uses flash-backs to achieve this as the play switches occasionally to scenes from the past.

One of the most fascinating factors in Old Story Time is the way Rhone employs obeah. Miss Aggie distrusts her neighbours because she distrusts black people and is convinced they turn to obeah to work against her out of envy at the success of her son. She causes the major dramatic conflict in the play by turning to obeah since she believes her son is in bondage due to the obeah employed by his wife. Her son, himself bears a grudge against his mother and hatred of his white tormentors which he carries around with him for thirty years.

Rhone presents these, including self contempt, as the real afflictions that plague the characters, not obeah. The character who understands obeah best is Pa Ben who is the only one to recognise that what they need is not obeah but to purge themselves of the ills that they harbour within their consciousness and their attitudes. Obeah is played out in the drama, but Rhone uses it as a dramatic device and a metaphor representing the real social and personal ills.

It is only when they learn to dispel those that the danger caused by their meddling in obeah which they little understand is averted at the end.