Dear Editor,

Ever since Simon Bolivar, the nineteenth century Latin American Liberator, organized the Congress of Panama in 1826, Latin American leaders have been hankering after regional integration. To make a good living in our times, countries must cultivate competitive and world class social and economic learning institutions capable of accommodating themselves to prevailing conditions. Regionalism can help to overcome the disadvantages of size and provide better opportunities for us to exploit our comparative advantages. The broad vision of the UNASUR rightly recognises the reality of globalisation and hence the need to address regional asymmetries if its members are to participate adequately in the global scheme of things.

According to Article 4 of its Constitutive Treaty, the Union is governed by a Council of Heads of State and Government, a Council of Ministers of Foreign Affairs, a Council of Delegates and has a General Secretariat. There are also sectoral Ministerial Councils. For example, the South American Council of Health was established in 2009 with the objective of creating an integrated space in which health is a fundamental human right. The following tables are given to help the formation of a comparative perspective.

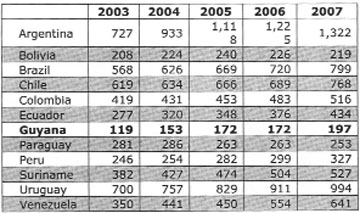

GDP per capita PPP (Constant 2005 international $)

*2005 data: 2009 not provided

Of course, it would be reckless not to note that insofar as the construction of regional integration institutions is concerned, the Latin American and Caribbean region may be second to none: aspirations appears to have gone ahead of reality. Speaking of the more recently (23/02/10) proposed “Community of Latin American and Caribbean States,” which excludes the United States and Canada, an editorial in Brazil’s Estadao newspaper (25/02/10) had this to say: “CELAC reflects the disorientation of the region’s governments in relation to its problematic environment and its lack of foreign policy direction, locked as it is into the illusion that snubbing the United States will do for Latin American integration what 200 years of history failed to do.”

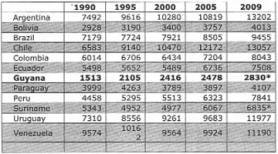

health expenditure per capita, PPP (constant 2005 international $)

Good intentions aside, others have identified difficulties, a few of which we need to briefly consider. Professor Nick Allen (“The Union of South American Nations, The OAS and Suramerica:” University of Baltimore School of Law, 2010) inter alia, argues that Article 3 of the UNASUR’s Treaty commits a signatory to some twenty one objectives and that failure to make good faith efforts to meet these objectives could render a state politically isolated. “The result could be economically and socially detrimental to the state, even disastrous, should the state be a relatively small player in South American affairs and dependent on others for import and export activity and investment.”

Secondly, the manner in which third parties are to be dealt with also deserves noting since it appears to require UNASUR’s co-operation when members are dealing with other organizations or nations and this in turn requires that such policies or programmes to be ‘adopted’ by UNASUR by way of Article 13 which is a minefield. Allen puts it thus in relation to another article which also deals with the third party process, “At the very least, Article 15 appears to require UNASUR’s cooperation in the case of a conflict with either OAS or even with another nation such as the United States. Of course some South American governments would hesitate to take such a course of action, especially when environmental, trade, and energy disputes are involved.”

Finally, the UNASUR process of dispute settlement is very restrictive. While many international organisations usually allow their members multiple ways of ending disputes (negotiation, good offices, mediation, conciliation, arbitration) before becoming involved, UNASUR Article 21 offers only two: direct negotiations or resolution by way of the organization. Thus states may feel their options limited and UNASUR become overextended in “addressing disputes better left to politically-detached third parties such as an arbitral tribunal or an independently-based constitutional court. At any rate, though, the UNASUR approach to conflict resolution is one more matter that a state contemplating ratification must consider as potentially adverse to domestic policy” (Ibid).

Much consideration also needs to be given to the process of economic integration. Professor Antony Venerables (“Regionalism and Economic Development,” IDB Conference Paper, 2001) contended that opportunities are limited in South/South regional arrangements. “Poorer countries are likely to experience trade diversion and possibly real income loss as they import goods from their partners rather than the rest of the world. North-South agreements typically offer better opportunities as they promote export growth in line with comparative advantage and may also open the way to fuller participation in global production networks.”

UNASUR is a relatively young organisation and one should not proceed as if it is developed and in full bloom. What the above observations seek to indicate is that a small, poor country with significant border problems such as Guyana needs to consider carefully, transparently and strategically its quest for regionalism if it is to enhance the benefits and mitigate the dangers.

Yours faithfully,

Henry B Jeffrey