Valuable or important books going out of print is a recurring issue everywhere. Very often a researcher, a student, or just any reader will hear that the text they need is out of print. Sometimes it is desirable to have a text available because of its great worth, its historical/archival value, its importance to a country’s literary heritage, the fact it is the surviving work of a particular author of note, or because it is a ‘classic.’ But such compelling arguments notwithstanding, publishers will rarely be anxious to reprint because it will not be profitable. Researchers, scholars or bibliophiles are relatively few in number and will not normally move a publisher to reprint.

However, there are times when publishers will take a deliberate step to reprint for different reasons. Faber started a series in the late 1990s to reprint selected works from the Caribbean and Latin America with novelist Caryl Phillips as one of the series editors. They redid Harris’s evergreen Palace of the Peacock and Marques’s One Hundred Years of Solitude. A German publisher went into the archives and republished a whole series of Caribbean texts in what was famously known as Klaus Reprints.

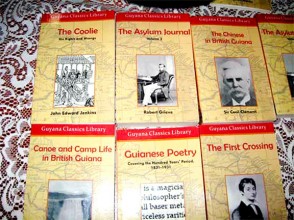

Now, Guyana’s new venture, The Caribbean Press, has embarked on its inaugural project, which is republishing Guyanese texts in a series called ‘The Guyana Classics.’ Several texts have been selected and put back in print because of their marked importance to the Guyanese literary heritage and their archival or historical value to the nation’s literature or history; or because they are regarded as ‘classics.’ After an initial production of copies for educational purposes, including wide distribution out of the office of Minister of Culture Frank Anthony, among schools across the country, the intention is to have much wider public circulation and then to move into the publication of works by contemporary Guyanese authors in a different project intended to relieve the scarcity of local publishing opportunites.

Now, Guyana’s new venture, The Caribbean Press, has embarked on its inaugural project, which is republishing Guyanese texts in a series called ‘The Guyana Classics.’ Several texts have been selected and put back in print because of their marked importance to the Guyanese literary heritage and their archival or historical value to the nation’s literature or history; or because they are regarded as ‘classics.’ After an initial production of copies for educational purposes, including wide distribution out of the office of Minister of Culture Frank Anthony, among schools across the country, the intention is to have much wider public circulation and then to move into the publication of works by contemporary Guyanese authors in a different project intended to relieve the scarcity of local publishing opportunites.

It is of interest to take a brief look at the second set of six texts now launched in this series by the General Editor David Dabydeen, leading Guyanese novelist, poet, critic, and one of the most prominent writers and academics in the UK. Each text in its own right has a place in the nation’s literature and history and fit the larger purpose of reminding Guyanese of “our reputation for scholarship in the fields of history, anthropology, sociology and politics,” of a history in which “the refinement of art and that of sugar were one and the same process,” and “that all Guyanese can appreciate our monumental achievement in moving from Exploitation to Expression.” (President Bharrat Jagdeo in the Series Preface).

These are references to the peculiar history of “Modern Guyana” as it is called in The Guyana Classics Library series, which began with economic exploration and continued with economic exploitation, but which also contained the wonders and beauty of the ‘colony.’ Most of the texts recently launched are historical, each in its own sphere of importance, while two are in the category of literature. These are of some relevance to the significance of the first text in the series, Walter Ralegh’s narrative which may be regarded as the inaugural publication in both the history and the literature of Guiana, with its influence on the imagination and its triggering of a history of gold and economic interests.

The early explorers would have confronted the indigenous people and there are several texts which document the various resulting experiences and details of anthropological interest. Along with the well known accounts of the likes of Walter Roth, Schomburgk and WH Brett, there is the earlier nineteenth publication, Indian Notices by William Hilhouse. It has the alternative (explanatory) title of ‘Sketches of the habits, characters, languages, superstitions, soil, and climate of the several nations; with remarks upon their capacity for colonization, present government and suggestions for future improvement and civilization. Also the ichthyology of the fresh waters of the interior.’

Mary Noel Menezes had edited and introduced an earlier republication of Hilhouse, whom she described as a “Las Casas of British Guiana” who “did not hesitate to condemn the abuses of the system of government over the Indians.” He lived among the Akawaios between 1815 and 1840, and became one of them to the extent that in his writings he makes an interesting first person reference: “To a stranger on his first arrival among us, no object is so surprising, so interesting, and occupies so completely all the better feelings of his heart, as the appearance of the free aborigines.” He focused with “outspoken and unwelcome candour” on his observance of “the unfeeling neglect, which still allows the Indian to remain poor, idle and ignorant.” This, according to Menezes, “won for him the hearty dislike of Governors, Members of the Courts, Protectors of the Indians, and Postholders.”

Two of the recent ‘classics’ reprints are on the subject of plantation slavery. One of them is about another advocate for the rights of a disadvantaged people. It is The Demerara Martyr by Edwin Angel Wallbridge first published in 1848 and it is the Memoirs of the Rev John Smith, Missionary to Demerara. Smith is well known for his association with the 1823 slave rebellion in Demerara. This reprint makes available to contemporary readers his full story. The book contains an ironic reference which could well serve as one of the rationales for reprinting The Guyana Classics. In the appendices to the book a speaker tells the British Parliament that Guiana is “a Colony, where books cannot be obtained, except at intervals, and then at a very great expense.” And that was in the early nineteenth century.

The next historical text also involves Sister Menezes. It is a reprint of her seminal work on The Portuguese of Guyana: A Study in Culture and Conflict, first published in 1993. This text consists of a collection of historical studies researched and written by Menezes to fill a vacuum since there was insufficient documentation of the history of the Portuguese in Guyana. It covers their activities in the second half of the nineteenth century and moves right through to references of great interest to the contemporary Guyanese society. There are important insights into the cultural contributions of the immigrants from Madiera including the Portuguese Amateur Dramatic Club and many other activities regarding their substantial involvement in the local theatre, which flourished in the late nineteenth century.

Just as The Portuguese of Guyana documents some of the historical foundations of Guyanese theatre and music (besides politics, sports, culture and commerce), the novel Lutchmee and Dilloo (1877) by John Edward Jenkins represents an important contribution to modern Guyanese fiction. It also compares to Hilhouse and John Smith because of its good intentions. It is the first known fictionalised account of the lives of indentured Indians in British Guiana and a pioneer Guianese novel of the late nineteenth century. It was written by Jenkins, an Englishman, “to alleviate the living and working conditions of plantation labourers through a cultural appeal.” But despite its sympathetic stance on behalf of the oppressed “coolies” and “Hindoos,” its writing betrays a class position and racial stereotyping in the simplification and pidginised version of speech given to them. This is borne out by the observations in Joseph Jackson’s ‘Introduction,’ and by Dabydeen and by Jeremy Poynting.

The second classic in the line of fiction represented in this set of reprints is important and worth republishing for other reasons. Dabydeen’s first novel The Intended (1991) makes available a novel from the new generation of Caribbean writers experiencing and fictionalising migration to Britain after the older pioneering brigade of the Naipauls, Lammings, Mittelholzers and Selvons. Also after Harris’s Carnival and Roy Heath’s The Shadow Bride, it is the third winner of the Guyana Prize for Fiction (1992). It fulfils one of the aims of the Classics Library series, which is also to pay attention to making available and circulating Guyana Prize books. Heath’s novel was also reprinted.

The sixth book in this group is something of a herald. It actually allows a look into a forthcoming commemoration to be observed by the Classics Library; that is the United Nations declaration of 2011 as the International Year of People of African Descent. Hearing Slaves Speak by Trevor Burnard is a remarkable document; it results from the discovery of a great volume of complaints made by enslaved people in their own words, testimonies before the Fiscal, the senior legal officer in the colony. Burnard edited and reproduced 92 narratives recorded between 1819 and 1832.

No doubt more will be heard about this reprint.