Bethlehem, the birthplace of Christ, Jerusalem and that area in the Middle East known as the Holy Land, is now one of the most intense trouble-spots of tension, war and conflict in the world. This is the strip of land where the son of God walked to bring “peace on earth and goodwill to all men.” All these ironies are reflected in the great Christmas poems.

Christmas is such a commercial success as the world’s most popular festival, that it is easy to find hundreds of verses about it, including several manufactured as a part of the great money-making industry that it is. It has all the characteristics of a traditional festival, and literature, including great literature, is a part of it. ‘Great literature’ because, after sifting through the abundance of merry, festive trivia and the large volumes of Christian poetry, there are to be found truly profound works of literature inspired by or otherwise relating to the season.

As a festival, Christmas has many roots, including ancient European religious rituals, Roman customs and secular celebrations, but had its greatest ascendancy as the most important event in the Christian calendar to celebrate the birth of the Christ.

As a festival, Christmas has many roots, including ancient European religious rituals, Roman customs and secular celebrations, but had its greatest ascendancy as the most important event in the Christian calendar to celebrate the birth of the Christ.

However, like most religious festivals it has factors of outreach in which these beliefs are expressed in many dramatic ways to the rest of the world. This has made it into an international popular festival with customs, traditions and a mythology that have nothing to do with Christianity.

The literature that has arisen reflects all of these. Among the verses, for example, are many that are Christian, stating the religious belief, sometimes deliberately designed to remind readers that the season is really about their faith. At the root of it all is the original poetry of the Holy Bible : “For God so loved the world, that he gave his only begotten son, that whosoever believeth in him shall not perish, but have everlasting life” (John 3: 16). However, many recent Christian poems were designed to remind readers of this biblical proclamation in the face of the growing secular, popular and commercial celebrations that believers feel has replaced the original meaning of the festival.

One poem is called ‘Why Jesus is Better Than Santa,’ setting out the brevity, ephemeral nature and superficiality of the seasonal gifts and celebrated characteristics of Santa Claus as against the depth, sense of eternity to be found in Jesus who is ‘the gift’ to the world. Another is ‘The Week Before Christmas,’ which describes all the decorations and activities leading up to Christmas Day that keep people so busy they cannot remember Jesus. It is a parody on the poem ‘The Night Before Christmas’ which is the virtual bible of Santa Claus mythology.

However, there are also the great works of literature which arise from all this. Another of the original verses is John 15:13 from The Bible, which goes “Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends.” Charles Dickens used this in his great novel, A Tale of Two Cities, to tell the story of a lawyer Sidney Carton, who allowed himself to be killed instead of his friend Charles Darnay during the French Revolution. Carton had the bad reputation of a man given to drink, while Darnay was the sober bright star, but Dickens made it clear that Carton was the better man, who actually did Darnay’s work for him and eventually sacrificed his life to save his friend.

And Dickens, it is to be remembered, wrote the most famous of Christmas novels, A Christmas Carol, about the reformation of Ebenezer Scrooge, the great archetype who gave his name to those who are stingy and who hate Christmas.

Then there are the important ‘Christmas Poems.’ While the Christian poems referred to above have little to recommend them in terms of poetic merit except their religious messages, the memorable works that make an impact are mainly oblique to these themes and make more resounding statements.

Perhaps the best known of these poems is ‘The Night Before Christmas’ by Clement Clarke Moore of New York. It was first published in The New York Sentinel under its original title ‘A Visit From St Nicholas’ on December 23, 1823, and famously begins:

T’was the night before Christmas and all through the house,

Not a creature was stirring, not even a mouse;

The stockings were hung by the chimney with care,

In the hopes that St Nicholas soon would be there . . .

Well, St Nicholas did appear, and the description of him, his sleigh and his reindeer created a great deal of the parallel mythology of Christmas. This poem has the reputation of being the first known on this subject in which Santa was described in detail, setting down his appearance and almost everything about him which became standard fare thereafter. It is an important part of the origins of Christmas as a modern secular festival with beliefs in a mythology quite different from the Christian one.

However, there are challenges to the authorship. The poem was first published anonymously and became, according to Wikipedia, “arguably the best known verses written by an American.” Moore had written it to amuse his children on Christmas Eve 1822, and never wanted it published under his name until persuaded by the children to do so in 1844. But critic Donald Foster claimed it was really written by another New Yorker of Dutch origin, Major Henry Livingston, Jnr.

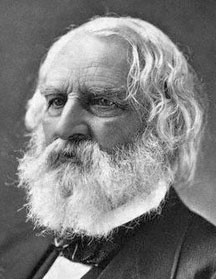

While those rhythmic, lilting verses became the most popular, one of the most notable Christmas poems out of America introduced a disturbing note to poems of the season. Prominent American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wrote the following in ‘Christmas Bells,’ 1864.

I heard the bells on Christmas Day

Their old familiar carols play,

And wild and sweet

The words repeat

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!

And thought how, as the day had come,

The belfries of all Christendom

Had rolled along

The unbroken song

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!

But Longfellow soon renders that theme ironic when he brings in references to the American Civil War and the discordant notes that it wrung.

Then from each black accursed mouth

The cannon thundered in the South,

And with the sound

The carols drowned

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!

It was as if an earthquake rent

The hearth-stones of a continent,

And made forlorn

The households born

Of peace on earth good-will to men!

And in despair I bowed my head;

“There is no peace on earth” I said;

“For hate is strong,

And mocks the song

Of peace on earth good-will to men!”

After that note of despair the poem ends by saying good will triumph over evil, but it had developed a mocking sarcastic chorus. This element of the devastating civil war certainly gives the poem meaning, taking it beyond a simple decorative verse. So discordant was it that, according to Wikipedia, “the references to the war were removed when the poem was set to music by John Baptiste Calkin in 1872.”

In similar vein, others of the more outstanding ‘Christmas poems’ contain one unsettling note or another as they reflect on the state of the world. Derek Walcott’s Season of Phantasmal Peace does not have a single word mentioning Christmas, but is about the peace of the season. On the other hand TS Eliot’s Journey of the Magi and WB Yeats’ The Second Coming are questionable as works of or about the season because of their timing, airs of disquietude and notes of disharmony, despite their titles and reference points. Longfellow’s poem reflects in 1864 in the American South the same mockery of peace on earth that in 2010 rocks the birthplace of Jesus who Christians say came as a gift to the world at Christmas.