By Ruti Teitel

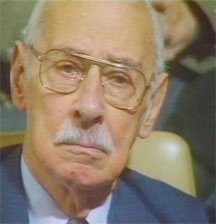

LONDON – Late last year, the former dictator General Jorge Videla was convicted and sentenced to life in prison for his role in Argentina’s “dirty war” of the 1970s, including the torture and execution of unarmed prisoners. These offences were perpetrated decades ago. What can such a verdict mean so many years after the restoration of democracy in Argentina?

Prosecuting Videla and other perpetrators was made possible by path-breaking case law undertaken by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights. The court has required that amnesties granted to political and military leaders in Argentina and other countries in the region as part of a transition to democracy be set aside. It has held that accountability for the crimes of the dictators is a human right – and thus trumps the impunity gained by many Latin American dictators as a condition of allowing democratic transitions.

The most recent decision of the regional tribunal, in mid-December, overturned a 1979 Brazilian amnesty law protecting military officials from prosecution for abuses committed during the country’s 21-year military dictatorship. “[T]he provisions of the Brazilian Amnesty Law that prevent the investigation and sanctioning of severe human rights violations,” the tribunal ruled, are “incompatible with the American Convention.” The effect is to require that those who were in charge answer for the forced disappearances in Araguaia of 70 peasants in an anti-guerrilla campaign. In these cases, victims, activist lawyers, and advocacy organizations turned to the regional human-rights court after exhausting their options at home. The domestic political and legal culture was still not ready to face squarely the ghosts of the authoritarian past. Brazil’s own High Court, for example, had recently sustained the constitutionality of the amnesty law, which was supported by successive Brazilian governments, all of which – including Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s center-left administration – evaded seeking accountability for the crimes committed by Brazil’s former military dictatorship.

The most recent decision of the regional tribunal, in mid-December, overturned a 1979 Brazilian amnesty law protecting military officials from prosecution for abuses committed during the country’s 21-year military dictatorship. “[T]he provisions of the Brazilian Amnesty Law that prevent the investigation and sanctioning of severe human rights violations,” the tribunal ruled, are “incompatible with the American Convention.” The effect is to require that those who were in charge answer for the forced disappearances in Araguaia of 70 peasants in an anti-guerrilla campaign. In these cases, victims, activist lawyers, and advocacy organizations turned to the regional human-rights court after exhausting their options at home. The domestic political and legal culture was still not ready to face squarely the ghosts of the authoritarian past. Brazil’s own High Court, for example, had recently sustained the constitutionality of the amnesty law, which was supported by successive Brazilian governments, all of which – including Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s center-left administration – evaded seeking accountability for the crimes committed by Brazil’s former military dictatorship.

In Argentina, even under President Raúl Alfonsin, the first democratically elected president following the military government, extrajudicial executions perpetrated by the country’s police accounted for one-third of all homicides. Similar abuses were committed by Peru’s security services during the 1990’s – crimes for which former President Alberto Fujimori is now paying.

All of this shows the tenuousness of civilian control and institutions, despite 30 years of democracy. New democracies face many political – and often economic – challenges. Making the police and the security services accountable can be a particularly tall order in the early years of a new and often fragile democratic regime. But not giving up on accountability, despite the passage of time, sends an important message about human rights, and the distinctive nature of these offenses as “crimes against humanity.”

This is not just a matter of Latin America’s particular legacy. Often, political leaders and military and security elites have proven as shrewd and tenacious in avoiding justice as they showed themselves cunning and brutal in doing injustice. They should never be confident that they can live scot-free. The International Criminal Court has no statute of limitations, and we rightly continue to pursue and prosecute the perpetrators of the Holocaust.

Years later, what’s at stake is not just punishment, but also political truth, which requires setting limits on official rationales for repression. Argentina’s military regime, after all, framed its “dirty war” as an offensive against so-called “terrorists,” rather than as what it was: wanton, arbitrary persecution of citizens with diverse ideologies and class backgrounds.

That lesson, handed down along with the judgment against Videla, vindicates efforts to establish a global rule of law. Tyrants everywhere – and more than a few democrats – would do well to take note.