Dear Editor,

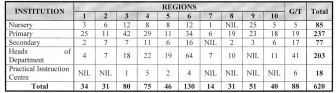

The vacancies advertised by the Teaching Service Commission in the Sunday papers of January 16, 2011 total 620, identified as follows:

a) Nursery – 85

b) Primary – 237

c) Secondary – 77

d) Heads of Department (Primary and Secondary) – 203

e) Practical Instruction Centres – 18

Examination of the various texts reveal some interesting, if not wholly disturbing, indicators of the extent to which some regions are bereft of relevant qualified human resources.

The table following provides an insight into the incidence of vacancies across the named regions, at the various levels of the teaching institutions affected.

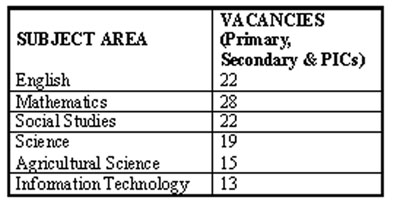

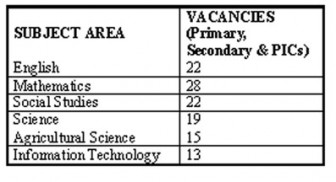

It is important to understand the critical value of heads of department (HoDs) to the system. The following are only some of the various areas of expertise for which vacancies for HoDs have been advertised for primary and secondary schools.

Areas like Home Economics and Business Education show 25 and 23 vacancies respectively.

One ponders the implications of these statistics. Even if in a perfect world all the vacancies were filled by applicants from within the system, how and wherefrom will their vacated positions be filled in turn. In essence therefore the ‘hole’ remains open.

There appears to be no indication of an immediate source to be tapped which can supply the range of skills required. If, as one suspects, the published vacancies reflect a chronic deficiency in the education sector, then the latter can hardly be satisfying needs and achieving targets, as is wont to be proclaimed.

For example, with the depletion of qualified personnel to deliver English, one must wonder what language is utilised for teaching and learning – critically at the Nursery Level. At the same time it is unacceptable that in a technological age a small country can claim to be ‘developing’ in the face of a deficit of teachers in Mathematics, Science, Agricultural Science, and Information Technology – to point to a few examples. In the case of the last subject, how supportive will 90,000 laptops be in the current circumstances!

One is forced to speculate on the existence of a strategy to:

i) develop the institutional capacity to train more of the needed skills at a faster rate;

ii) retain those skills long enough to allow for effective transition of knowledge;

iii) design compensation and benefits packages that would not only attract and retain, but motivate stayers, create believers in a system that will recognise performance and encourage career seekers;

iv) provide a socially energising environment in which a pioneering corps of teachers will accept the challenge to contribute to the education and development of fellow citizens in the farther regions, while in turn learning to be models for the young under-exposed learner population.

It makes little sense to build accommodation for learners and not for their teachers.

But all this seems so long term – at a juncture when time is not on anybody’s side. There are already immediate concerns. The list shows 85 vacancies for nursery teachers of which 25 occur in Region 9, and 12 each in Regions 3 and 6 respectively.

Again at the primary level, Regions 3 and 6 are surprisingly shown as having the highest vacancies – 42 and 34 respectively; with Region 4 following with 29 and Region 1 with 25 vacancies.

Of the 77 vacancies reported at the secondary level the list shows Georgetown with the most vacancies – 17, followed closely again by Region 6 with 16. Region 4 comes behind with 11.

Needless to say, that this analysis is supported by a detailed breakdown of each of the vacant positions in each region and of course Georgetown.

What in effect the numbers are saying is that there is urgent need for the most intensive and exhaustive consultation amongst all the relevant stakeholders to address this potentially lethal haemorrhage in the country’s education system.

Yours faithfully,

E B John