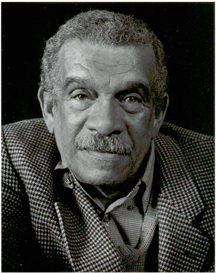

It was announced on January 24 in London that Caribbean poet Derek Walcott had won the TS Eliot Poetry Prize 2010 for his latest collection White Egrets. This was yet another triumph for the writer who has already won the Nobel Prize (1992) and brings him under international public gaze once again, basking in praises, garlanded by superlatives and the subject of old controversies and intimations of notoriety. While this latest crowning prompted the British media to dig up and return to past issues, it yet again causes the Caribbean to reflect on the career of its greatest poet-playwright and why he is of importance to the region.

The TS Eliot is the richest prize for poetry in English awarded each year to the best book published in the UK and Ireland. It was established in 1993 by the Poetry Book Society of England to celebrate the society’s 40th birthday and in honour of Eliot who was one of its founders in 1953 and who is regarded as the most influential poet of the 20th century. It was hailed as a deserving victory for Walcott who won from a shortlist of 10 poets whose work was said to reflect the very rich harvest of books of poetry published in 2010 and represented very strong competition, although there were conflicting statements made about that.

The TS Eliot is the richest prize for poetry in English awarded each year to the best book published in the UK and Ireland. It was established in 1993 by the Poetry Book Society of England to celebrate the society’s 40th birthday and in honour of Eliot who was one of its founders in 1953 and who is regarded as the most influential poet of the 20th century. It was hailed as a deserving victory for Walcott who won from a shortlist of 10 poets whose work was said to reflect the very rich harvest of books of poetry published in 2010 and represented very strong competition, although there were conflicting statements made about that.

Poet Anne Stevenson, Chairman of the Judges, in her citation said, “this year’s exceptionally strong and varied shortlist made it difficult to choose the winner, but the judges felt that Derek Walcott’s White Egrets was a moving, risk-taking and technically flawless book by a great poet.” But she also declared, “it took us not very long to decide that this collection was the yardstick by which all the others were to be measured,” and recognised Walcott as “a very great poet – one of the finest writing in English.” She commented on the strength of the shortlist, narrowed down from many other very good books in “a bumper year for poetry of a very high order.” This shortlist of 10 included Annie Freud, a grand-daughter of Sigmund Freud, and Seamus Heaney. Heaney is another of the most brilliant contemporary poets who won the Nobel Prize in 1995 and the TS Eliot in 2006. Previous winners of the Eliot also include Ted Hughes and Carol Ann Duffy. Heaney, a native of Northern Ireland, is a very close friend of Walcott who has collaborated with him on one or two of his attempted projects in St Lucia. At one time they formed a notable trio with another famous poet, Joseph Brodsky.

On January 23, nine of the shortlisted poets read from their works in the Festival Hall of London’s South Bank in what was described as the largest audience in recent times. Walcott was not there. But the occasion was seized on by the English press as good time to unearth the recent scandal involving Walcott. He was one of three poets in line for the prestigious Oxford Professor of Poetry in May 2009 when one of his rivals circulated documents containing past allegations made against Walcott in 1982, in a smear campaign against him. Walcott withdrew from the race expressing “disappointment” at the “low and degrading attempt at character assassination.” Ruth Padel, (a direct descendant of Charles Darwin) who eventually got it, gave it up after just nine days, under severe pressure after admitting some responsibility for the campaign.

The media immediately remembered that, but they also recalled the elevated position Walcott holds among contemporary writers. He has been called the best poet writing in English, one of the leading poets of the 20th century, in addition to what the TS Eliot judges said about him and the high praise from the Swedish Academy who declared that “in him West Indian culture has found its great poet.”

That last comment, part of the Nobel citation, is very relevant to his place in the Caribbean. The book that brought him to the world’s attention was In A Green Night – Poems 1948-1960 (Jonathan Cape, 1962) which drew a mix of assessments including skepticism about his style and echoes of Marvell, Dylan and according to one critic “of almost everybody.” But that book celebrated the Caribbean with the poet vowing to “write verse crisp as sand,” to “praise lovelong” the jewels, ocele insularum, of the islands, “for beauty has surrounded our black children and freed them from homeless ditties.” From a book in which he virtually saw himself learning the craft through experience and experimentation, he turned out a series of others continuing with The Castaway, deepening an appreciation of the region and continuing to grow into greater prominence as one of two giants of Caribbean poetry. The other was Eddie Kamau Brathwaite, who during that time produced his first great trilogy (later put together as The Arrivants).

Other books began to win him less qualified respect among the critics. One of these was his first long poem Another Life, highlighting the colonial condition of a Caribbean wrenched by two styles emanating from Europe and Africa but dominated by English and the Classics. His poetry became so dominant that it is often forgotten that he is an equally weighty dramatist. During the same years his rise was also occasioned by such plays as Dream on Monkey Mountain (1970), The Joker of Seville (1974) and eventually The Odyssey in 1991, which indicated to all that he had arrived.

Earlier in his career he began experimenting with Greek mythology and hinted that one day a great poet of the Caribbean will emerge to do for the region what Homer did for Greece. After his second and greatest long poem Omeros (Faber 1991) the world seemed to have agreed that that great poet had arrived and he was Walcott, “the Homer of the Caribbean.” But the extent of his originality and the manner in which he interrogates the Caribbean, its history and its culture, proclaims that he is Walcott, not any imitation of Homer.

After that Walcott was to embark on a journey as a “fortunate traveller” which further escalated his reputation and deepened his style (no longer “wrenched” or “divided”) which prompted some critics to say he was getting better with age. But as he rose as a world poet, so did the Caribbean, despite books like The Bounty and The Prodigal reflecting his wanderings around Europe and North America. His most authoritative critic, Edward Baugh, had very early described him as a universal humanist and a citizen of the world, and in his monumental study of The Prodigal (Farrar Straus Giroux, 2004) pointed out Walcott’s intense Caribbeanness in language as he roamed the world and returned.

White Egrets (Faber and Faber, 2010) is in that mould, but very elegiac as The Bounty is. In it he is at ease with the world, some of whose places it reflects, even as he contemplates mortality. He settles down in rhythm and metre as he has in rhyme, choosing a calm, comfortable craft that helps the poem to move inobtrusively. He once told the British media “rhyme is an attempt to reassemble and reaffirm the possibility of paradise. There is a wholeness, a serenity with sounds coupling to form a memory.”

That wandering, that returning and that memory are all there in this work. The egrets have long been a preoccupation of his as he has returned to them in one way or another continually. The last poem in the collection is very significant. It is untitled, it is a return to the Caribbean and seems to go right back to memories which reappear and fade as he describes an island, probably St Lucia, with its mountains, coastal town, boats and, very importantly, the sea. Island landscape turns to pages of book and back as the vision sharpens and fades. But not unlike a major theme in the book it hints at the end of his career “as a cloud slowly covers the page and it goes / white again as the book comes to a close.” However, the emphatic, confident quality of the verse and its imaginative energy seem to suggest no such thing.

This page is a cloud between whose fraying edges

a headland with mountains appears brokenly

then is hidden again until what emerges

from the now cloudless blue is the grooved sea

and the whole self-naming island, its ochre verges,

its shadow-plunged valleys and a coiled road

threading the fishing villages, the white, silent surges

of combers along the coast, where a line of gulls have arrowed

into the widening harbour of a town with no noise,

its streets growing closer like a print you can now read,

two cruise ships, a tug, a schooner, ancestral canoes,

as a cloud slowly covers the page and it goes

white again and the book comes to a close.

Derek Walcott (White Egrets)