LONDON, (Reuters) – Floodlights, fireworks and a spectacular Sydney sunset heralded both a triumph for Kerry Packer and his rebel World Series Cricket (WSC) and the birth of the modern one-day game.

November 28, 1978, was the day the Australian media mogul gambled and won with his audacious ploy to stage a day-night one-day match illuminated by six freshly erected floodlight towers at the Sydney Cricket Ground and featuring a white ball and coloured clothing.

A boisterous crowd estimated at 50,000 packed the famous ground to witness the WSC Australia side defeat West Indies. Many more watched the game on television aided by a host of the eye-catching technical innovations already introduced by Packer’s Channel Nine.

Man-of-the-match Dennis Lillee smiled at the assembled reporters afterwards. “When Mr Packer started WSC, the Australian Cricket Board said: ‘We’ll let the people be the judges’,” Lillee said. “It looks like they have.”

The great fast bowler had signed for Packer in the previous year in the justifiable belief that he and his colleagues were being paid a pittance for their efforts even though test cricket was booming in Australia.

West Indies, victors over Australia in the first World Cup final in 1975, also signed en masse as did a group of leading England, Pakistan and South African players.

Their collective faith in the new venture, though, was shaken when the fans failed to turn up for the so-called five-day SuperTests in the 1977-78 season, preferring to watch the official Australia side play India in a consistently gripping series.

COMMERCIAL REALITIES

One-day night cricket in the second and final season transformed the fortunes and profile of World Series Cricket, although Packer remained first and foremost a money man. In 1979, the Australian Cricket Board sued for peace and gave him the television rights he had sought in the first place and the rebel circuit was dissolved.

Cold commercial realities had also been behind the decision to launch the first official one-day competition in England on May 1, 1963, with a match between Lancashire and Leicestershire at Old Trafford in the new Gillette Cup.

The traditionalists shuddered and the Wisden Cricketers Almanac could not bring itself to acknowledge the competition by name, calling it instead the Knockout Cup.

Nobody, though, could realistically object to the injection of new money into a domestic game in crisis as attendances plummeted in the county championship.

The new format also appealed to the restless imagination of England and Sussex captain Ted Dexter. Dexter realised more quickly than most that limited-overs cricket demanded a fresh approach and he was ruthless enough to place every fielder on the boundary in the closing stages of the first final against Worcestershire at Lord’s.

Sussex duly won by 14 runs before a packed house and the leading sportswriter of the day, Peter Wilson of the Daily Express, commented: “If there has ever been a triumphant sporting experiment, the knockout cricket cup for the Gillette Cup was that experiment.”

One-day cricket had come to stay but it was still seven years before an international limited-overs match was staged and then only because rain forced the abandonment of the third test between Australia and England scheduled to start on Dec. 31, 1970.

PACKER LEGACY

Australian Board of Control chairman Don Bradman announced that a one-day match of 40 eight-ball overs would be staged as well as an extra test and a crowd of 46,006 turned up to watch a home side victory. It escaped nobody’s attention that the attendance exceeded the five-day aggregate for the first test in Brisbane.

A World Cup was inevitable and it was the game’s great good fortune that the 1975 tournament featured some of the finest players ever and a final between eventual champions West Indies and Australia still regarded as the best of them all.

Only 18 one-day internationals in total had been played before the World Cup but in the following decade the one-day game exploded in popularity.

The Indian board, in particular, embraced one-day cricket after their team’s unexpected victory over West Indies in the 1983 final.

India and Pakistan were awarded the 1987 tournament after promising to double the prize money and within a decade India had become the richest and most politically powerful country in world cricket. Television money poured in and various one-day tournaments blossomed in the Middle East.

There was a price to pay. Test cricket became very much a poor relation in India and the proliferation of one-day cricket fuelled the illegal gambling industry on the subcontinent where punters can bet on every delivery. That in turn undoubtedly contributed to the corruption scandals which besmirched the game in 2000 and again a decade later.

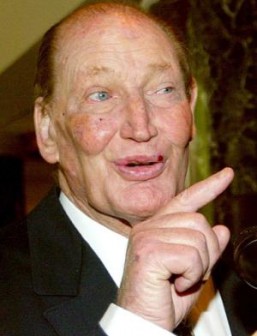

Packer, who died in 2005 at the age of 68, made a great deal of money out of televising cricket over a quarter of a century.

His legacy, though, far exceeds his personal pecuniary ambitions. The modern one-day game, which will be on display at the 10th World Cup on the Indian subcontinent this month, is essentially the version developed in the two extraordinary years of World Series Cricket.

As Wisden’s obituary pointed out, Packer, for better or for worse, “was the media tycoon whose intervention in cricket created the finances, shape and tone of the modern game”.