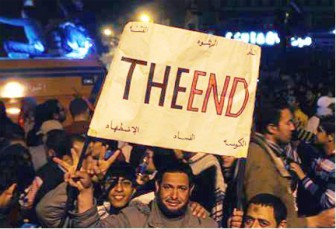

CAIRO, (Reuters) – Egyptians who toppled Hosni Mubarak yesterday may still have more to do to ensure a military council now in charge transfers power to civilian hands.

The army has not spelled out any transition plans it might have. The best deterrent to any attempt to maintain military rule could be the street power of protesters who showed Mubarak they could render Egypt ungovernable without their consent.

Egypt is plunging into new territory after Mubarak’s 30-year rule, with its legacy of corruption, bureaucracy and immobility.

Any government will face huge social and economic problems, but one freely chosen by the people could also look to harness the vast creative energy and patriotic pride so evident on the streets jammed by demonstrators for the past 18 days.

“Egyptians have to be careful that their revolution does not get hijacked,” said Hassan Nafaa, professor of politics at Cairo University, referring to the former military-backed system.

“It is now in the hands of the military council, and it is supposed to carry out the demands of the revolution, and therefore the people have to carefully follow how these demands will be applied,” he said.

The military could send a good signal by sacking a cabinet hastily appointed by Mubarak as a sop to protesters and replacing it with “one that represents the people, the opposition forces and the forces that sparked the revolution”, Nafaa said.

“NEW ERA OF FREEDOM” Egyptian analyst Diaa Rashwan anticipated martial law measures to freeze the constitution and dissolve the parliament elected in November in a poll that was blatantly rigged by Mubarak’s National Democratic Party.

But he voiced confidence that Egypt’s newly empowered citizens would ensure that a “new era of freedom” would survive. “No one can fear for the fate of Egyptians any more,” he said.

Egypt’s interim leader is a pillar of the old guard: Defence Minister and armed forces commander Mohamed Hussein Tantawi, 75, long derided by critics as Mubarak’s loyal “poodle”.

He leads the Higher Military Council, which Vice-President Omar Suleiman said would run Egypt until a presidential poll, that had been set for September. The army vows it will be fair.

The future of Suleiman himself, once Mubarak’s intelligence chief mocked as an “agent” by demonstrators, is now unclear.

“There must be serious questions over how acceptable Suleiman will be, given his support for Mubarak,” said Julien Barnes-Dacey, Middle East analyst at Control Risks. “He has to come up with sessions very quickly for comprehensive reform.”

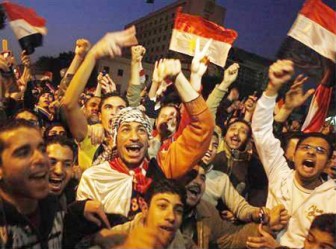

For now, hopes of Egypt’s pro-democracy camp are high.

“We have waited for this day for decades,” Nobel laureate Mohamed ElBaradei told Reuters. “We all look forward to working with the military to prepare for free and fair elections. I look forward to a transitional period of co-sharing of power between the army and the people.”

PIVOTAL MOMENT

The United States, which has tried to balance its desire for stability in a key Arab ally with support for democratic change, has welcomed what U.S. Vice President Joe Biden called a “pivotal” moment in history for Egypt and the Middle East.

The transition in Egypt must be one of “irreversible” change, he said.

Robert Satloff, executive director of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, said the military leadership should “clarify very soon whether Egypt is under martial law or whether it has begun a true path toward democracy”.

Washington would want to see an end to emergency law and “creation of a broad-based national government that includes credible civilian figures to lead the country as it does its constitutional and other legal changes” before elections.

Brian Katulis, Middle East expert at the Center for American Progress in Washington and informal adviser to the White House, said Mubarak’s fall was only the start of a transition.

“Today in name, if not in fact on the streets, the people who have ruled Egypt since 1952 are still the same people, the same cadre of the military elite,” he said.

But having seized their destiny, Egypt’s 80 million people will want to shape it themselves, regardless of foreign powers.

Many Egyptians, secular and Islamist alike, might echo the words of Kamel el-Helbawy, a British-based Muslim Brotherhood cleric. “Today, a dictator becomes part of the past. We will not tolerate a stubborn man like him coming to power again.”