True to its origins as the initial outlet for the products of creative writing workshops at Cave Hill and even for the writing courses in fiction and poetry run by Bryce and McWatt, Poui is a school of experimentation. For years now it has been exhibiting newer forms of experimental work by successive generations of writers and this intensifies in Number XI. The short, sharp, fresh and sometimes startling pieces of short fiction that began to appear in previous volumes continue in this number, seeming to have matured into a conscious form of the short story in which succinctness, brevity and a Mervyn Morris-like frugality of words, meaning and statement are characteristic. In this volume Aajee’s Gift by Vashti Bowlah and Malika by Rob Leyshon are satisfying examples. Within that honed piece of gentle humour Leyshon deceives and surprises the reader at least thrice in his persona’s uncommon love affair with an automatic car wash machine, immediately and ironically followed by his unexpected appreciation of genuine human warmth, then the final turn of the screw in his hurrying home looking forward to the welcoming arms of his wife. It is a perverse, amusing, effectively satisfying tale.

True to its origins as the initial outlet for the products of creative writing workshops at Cave Hill and even for the writing courses in fiction and poetry run by Bryce and McWatt, Poui is a school of experimentation. For years now it has been exhibiting newer forms of experimental work by successive generations of writers and this intensifies in Number XI. The short, sharp, fresh and sometimes startling pieces of short fiction that began to appear in previous volumes continue in this number, seeming to have matured into a conscious form of the short story in which succinctness, brevity and a Mervyn Morris-like frugality of words, meaning and statement are characteristic. In this volume Aajee’s Gift by Vashti Bowlah and Malika by Rob Leyshon are satisfying examples. Within that honed piece of gentle humour Leyshon deceives and surprises the reader at least thrice in his persona’s uncommon love affair with an automatic car wash machine, immediately and ironically followed by his unexpected appreciation of genuine human warmth, then the final turn of the screw in his hurrying home looking forward to the welcoming arms of his wife. It is a perverse, amusing, effectively satisfying tale.

Another newish form found rising in Poui are the many pieces of prose poems and poetic prose. These range from the intensely postmodernist as in Ahinsa Timotio Bodhran’s How to Make Love to a Dying Rican to the almost fragment in Verguenza by the same author. From the more established writers come pieces that tell still intriguing discoveries about poets you thought you knew. Mervyn Morris can still startle with his verbal economy which gets even more deeply postmodern in his “Soundbite,” Best Wishes to Kamau from a Junior, in which the title threatens to be longer than the poem itself, yet it is meaningful significant statement. Similarly, McWatt who is very well known for his love poems and poems about the creative process, still takes you further with a fresh statement about writing poetry and expressions of love.

His bright ending rhyming couplet heightens the freshness while putting poetry and abstraction up against the reality of ordinary living. A similar sentiment is found in Edward Baugh’s “Soundbite,” Soundings (for Kamau Brathwaite) about the peasant woman minding black-belly sheep in the Barbadian countryside. Yet he connects the poetry and the consciousness of Brathwaite’s poetry to that woman and her class and the cultural groundings that come from connection with approving African spirits.

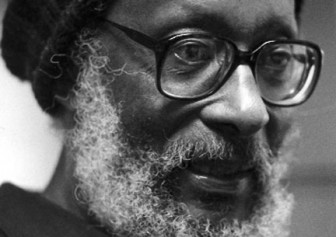

Both Morris and Baugh, five other poets, Funso Aiyejina, Pamela Mordecai, Martin Mordecai, Kwame Dawes, Niyi Osundare, are responding to what is the main theme in Poui XI. The whole volume is a tribute to Kamau Brathwaite in the celebration of his 80th birthday (May 11, 2010). It is appropriate for Poui to honour Brathwaite in this way since they are both marking significant anniversaries and are making statements about established literary traditions, which they both are. As one of the giants of West Indian literature, Kamau is known for his bold originality in language and versification and for his interrogating excursions into post-modernism.

Both Morris and Baugh, five other poets, Funso Aiyejina, Pamela Mordecai, Martin Mordecai, Kwame Dawes, Niyi Osundare, are responding to what is the main theme in Poui XI. The whole volume is a tribute to Kamau Brathwaite in the celebration of his 80th birthday (May 11, 2010). It is appropriate for Poui to honour Brathwaite in this way since they are both marking significant anniversaries and are making statements about established literary traditions, which they both are. As one of the giants of West Indian literature, Kamau is known for his bold originality in language and versification and for his interrogating excursions into post-modernism.

It is to be noted that his influence is significant.

Three of the established poets in their acknowledgement of his work admit to being influenced and inspired by him, and these include Aiyejina whose introduction was at the (then) University of Ife in Nigeria. Brathwaite’s styles of lineation and his way with words have influenced many others and this may even be seen in pieces by newer writers in this volume.

To strengthen the tribute and appreciation, seven extracts from Kamau’s recent unpublished work Missa Solemnis (2006) is published. In its characteristic Brathwaitian style, it is a long poem that integrates a picture of Barbados with the history of the Caribbean, the Middle Passage, slavery and its cultural heritage. The title is taken from Missa Solemnis, a work by Beethoven, first performed on April 7, 1824 in St Petersburg, and Brathwaite tells in his introduction how he discovered it while working in Ghana then called Gold Coast in 1953. It continues Brathwaite’s fascination with music in his poetry, especially jazz, and he finds effective expression in a continuous conversation with the classical and the Caribbean folk.

The poet explores places such as rural localities in his native Barbados in a way that he had done before in Mother Poem and Sun Poem, in a dialogue with the experience of the Middle Passage. There are echoes of his early Caliban poem in the extract Limbo, where the distinct rhythm is informed by the indigenous music, as are many other references. The limbo is linked to the trans-Atlantic slave trade, to the submerged consciousness, the descent and rise through African drums and the music. The poem’s several references include Barbadian villages and landscape, waterways and geomorphology, which he turns into parts of the cultural experience.

Poui XI is designed to present this feature of Brathwaite dramatically as the excerpts from the poem are interspersed with the other works which are expressions of a tradition. There are works which show the output of new writers and students of the art. Other works are the current preoccupations of established Caribbean writers. Some pieces were written as tributes to Kamau and reflect some of his preoccupations. There are others which reflect some stylistic influences, while many of the pieces provide samples of new traditions that have been emerging in contemporary West Indian writing.

Poui has come to be the place where all these streams and tributaries meet.