Dear Editor,

At its meeting held in October 2006, in Georgetown, the Council for Human and Social Development (COHSOD), considered, with much concern, the burning issue of the skills drain from the Caribbean region. The discussion highlighted the flight of trained nurses and teachers; and recommendations were received on how the continuing migration could be contained, including the development of mechanisms that would yield some compensation to the countries affected for the loss of human capital. Guyana at the time specifically addressed the matter with respect to its trained nurses, at the regional meeting.

It was recognised that with the implementation of the CSME, each member state could become vulnerable to the movement of a wider range of skills amongst sister territories.

This focus was consistent with that applied to the subject at the launching of the National Competitiveness Strategy Conference earlier in 2006. Both government and the private sector reached agreement on the implications of the skills drain for the growth of the economy and the development of the nation, and on the need for a relevant strategy to be developed as a matter of urgency.

Against that background, therefore, it is still timely to ask whether a retention plan has since been developed. This question was since posed by a visiting consultant who, after examining the status of the staff complement at one of the most critically important of the public sector agencies in Guyana, discovered that there were more than 40% vacancies in the established posts. This is an important question for which answers continue to be required, in relation to the wider public sector of the economy. Not only is a good proportion of public sector agencies similarly understaffed, but careful analysis is also needed to identify in the first instance, whether the issue is one of the rate of departure; the inability to attract suitably qualified personnel to fill the vacancies; or a combination of both.

Whichever the conclusion, available evidence suggests that a serious human resource crisis exists in the public sector. Arguably, it is the twin problem of attracting the requisite skills and the premature departure of existing ones. Is there a case to be made therefore for a coordinated retention plan?

It is within this context that perhaps one must view recent media reports indicating that a decision has been taken at the highest level to recruit teachers from overseas, including the Caribbean, utilising the CSME mechanism. This is certainly the correct route to follow in the latter regard. It is understood that the focus will be on capabilities in Mathematics and Science. There has since been several published perspectives expressed about this ‘initiative,’ some more informed than others. Presumably, however, the announced decision was based on certain extant facts, the implications of which were taken fully into account.

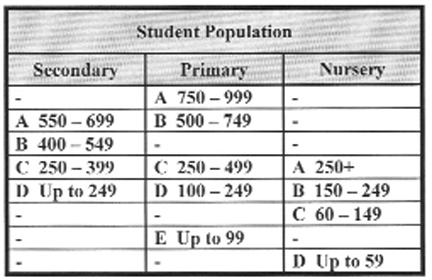

According to the Teachers’ Service Commission Notice 2011, published on Sunday, January 16, 2011, there exists a total of 620 vacancies. Of that number 207 vacancies were indicated as being heads of department – the ascription which is used for teachers specialising in a range of subjects – as exhibited in the Table following which focuses only on secondary school vacancies for purposes of this discussion.

Examination will immediately show that 26 specialist teachers in Mathematics and 19 in Science are required, and thus should constitute the target group for recruitment. These figures appear, at first glance, to not readily reconcile with the Education Minister’s reported assertion that some 50% of secondary schools need specialist Mathematics and Science teachers, for the simple reason that the number of secondary schools has not been identified – an important consideration for overseas recruitment, given the obvious geographical distribution involved.

Examination will immediately show that 26 specialist teachers in Mathematics and 19 in Science are required, and thus should constitute the target group for recruitment. These figures appear, at first glance, to not readily reconcile with the Education Minister’s reported assertion that some 50% of secondary schools need specialist Mathematics and Science teachers, for the simple reason that the number of secondary schools has not been identified – an important consideration for overseas recruitment, given the obvious geographical distribution involved.

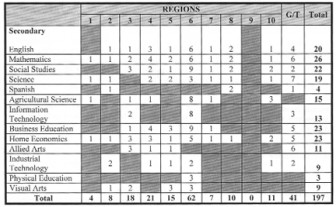

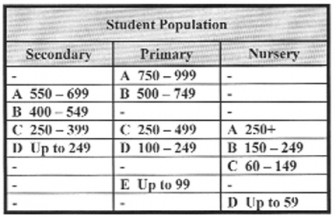

Another significant consideration is that the schools in the education system are graded as follows:

It is important to appreciate that at certain levels in the job hierarchy the grading of schools is a factor in determining the quantum of compensation.

It is important to appreciate that at certain levels in the job hierarchy the grading of schools is a factor in determining the quantum of compensation.

Then compensation in turn becomes even more complex, related as it also is to qualifications (and in some instances stipulated relevant experience). The apparent confusion obtains in the differentiation made between a ‘graduate’ and ‘non-graduate’ teacher. A ‘graduate’ is defined as one completing the statutory (2 years) training at the Cyril Potter College of Education; while a person leaving UG with a full degree still falls within the ‘non-graduate’ category – resulting in a substantial differential in basic pay.

These are substantive issues to be addressed with reference to overseas (Caribbean) recruits who, according to established CSME protocol, must be evaluated as suitable for employment within the purview of the regime which provides for the recruitment of skilled Caricom nationals. But surely our educationists already know that the matter of educational equivalencies will have to be carefully examined.

Having expertly cleared this hurdle, the administrators must address the sensitive issue of ‘conditions of employment.’ In this regard it would have been helpful to learn of a more studied reaction from the Guyana Teachers’ Union, rather than just a report that their members would expect parity to be applied, possibly overlooking the fact that within the CSME alone, five other exchange rates, in relation to the US dollar, apply. So that it would be useful to see the final Guyana dollar computation for personnel from the different exchange regimes, in relation to the same levels of jobs.

The GTU appears to expect that local personnel with equal skills and in comparable positions, will have access to the same/similar basic remuneration, although the possibility exists that adjustments at the level of ‘specialist’ teacher may overtake the (unadjusted) values of higher level jobs in the teaching hierarchy, namely headmaster/mistress and deputy. Needless to say the repercussive effect could trend further across the public sector.

Research will show that the teaching service salary structure consists of twenty-nine bands ranging from $38,602 monthly at the lowest level to $189,095 at the highest, as compared with fourteen public service bands ranging from $33,207 at the lowest minimum to $494,248 monthly at the highest maximum. Suffice it to say that eleven only of the latter bands easily absorb all 29 of the teaching service’s structure.

There is no questioning the relative disadvantaged position of this particular group of professionals who are held accountable – ultimately for providing the potential resources for the employment market.

What greater incentive could there be for them to seek alternative forms of employment, than that which inheres in the inequitabilities which currently obtain.

But the compensation package for overseas recruits may also have to take into consideration accommodation (and utilities); possibly transportation; and welfare benefits like NIS, for which there is provision through the relevant CSME regime.

When all the above is reconciled the recruits themselves would wish to weigh both the similarities and differences in their respective education structures, systems, and experiences on the ground. Matters of adequate infrastructure; security; the level of aberrant student behaviour in local schools; disciplinary procedures (for teachers and students); leave (including sick leave); reporting relationships, and differentials in governance structures are all likely to be explored.

Since the above list may not be exhaustive, it would appear that a preliminary approach to the proposed recruitment exercise would be to take the process to the target areas and thoroughly investigate the potential market, and the incentives that will prove effective in acquiring the human resources needed.

In the meantime serious consideration needs to be given to the overall sustainability of the project; as well as, more importantly, to reducing the skills drain by retaining existing resources, if only by raising the retirement age of teachers (and indeed all public servants) to at least 60 years. And of course pay better and provide improved conditions of employment.

Yours faithfully,

E B John