Dear Editor,

It would not have gone entirely unnoticed that France recently experienced substantial industrial unrest following the Sarkozy government’s insistence on raising the retirement age – an action critical to that economy, given the extent of public employment in that country.

In Britain recent legislation restrains employers from discriminating against employees on the basis of age. In other words, age should not be a basis for terminating a productive employee. Apart from the financial implications for pension schemes, and government schemes in particular, there are other substantive considerations to be taken into account, ie, the advantages and/or disadvantages which redound to employers, including private sector employers, who are confronted with a choice of this nature.

The fact is that there is need for a cohesive policy or set of guidelines to be developed, in light of an employment environment which is affected by the following, amongst other things, in Guyana for example:

The fact is that there is need for a cohesive policy or set of guidelines to be developed, in light of an employment environment which is affected by the following, amongst other things, in Guyana for example:

a) the persistent migration of skills – internally and across borders;

b) the increasing opportunities being developed and formally encouraged for the growth of small entrepreneurship;

c) the urgency to translate the vision of local businesses being competitive into reality, by accessing the right human resources;

d) the implications for the availability of relevantly qualified human resources in the face of the establishment of large employers, deliberately attracted by the declared national investment policy.

Already some of the more dynamic local companies are devising specific programmes, not only to replace lost skills, but more importantly, to retain those they now have. And while in some cases there tends to be a focus on technical skills, the paucity of managerial skills also gives pause for concern.

But what does all of this have to do with the matter of retirement and talk of an optimal pensionable age? While no confirmed statistics are immediately available, there is perceivable evidence of the rate at which retirees have had to be retained in the absence of appropriately qualified successors in a number of private entities, as well as public sector agencies (including the traditional public service).

The retirement age in the public service is as obtained in the colonial era – 55 years, certainly in the case of males. It is nevertheless puzzling that about three years after the attainment of independence a National Insurance Scheme was established in Guyana designed to provide superannuation benefit to contributors – but only at the age of sixty. It is unclear whether or not there was a realisation of the benefit qualification set being incompatible with the official retirement age of 55 for the public servant. The saving argument was, of course, that there was already a non-contributory pension scheme in place which kicked in, so to speak, at age 55. (Needless to say the private sector would have had little difficulty in adjusting the retirement age of employees to 60, if it were not already the case.)

More than forty years after substantial anecdotal evidence suggests that in the case of public servants the cost of living overwhelms the ability of most retirees not in the higher pay brackets, to sustain an acceptable quality of life on one such benefit package. So that the loss of, or reduction in, earnings in the five-year interval can have a deleterious effect on the final NIS superannuation benefit package at time of eligibility.

But perhaps the more critical constraint on the public servant’s earnings results from the application of the policy, over the last decade or more years, of across-the-board increases. The adjusted computation ends up with a disproportionate percentage of public servants ‘bunched’ at the minimum of their respective salary grades. This enervating exercise has also been indiscriminatingly extended to income/profit earning public sector organisations – a process which incidentally effectively values the contribution of the productive manager no more than that of the unskilled labourer.

This endemic malfunctioning of salary administration is patently counterproductive. Not only is good performance no longer recognised by the organisation, but it is also not rewarded – a clear incentive for movement outwards by those who are qualified and capable of doing better, leaving their pedestrian colleagues to stay an unpromising course.

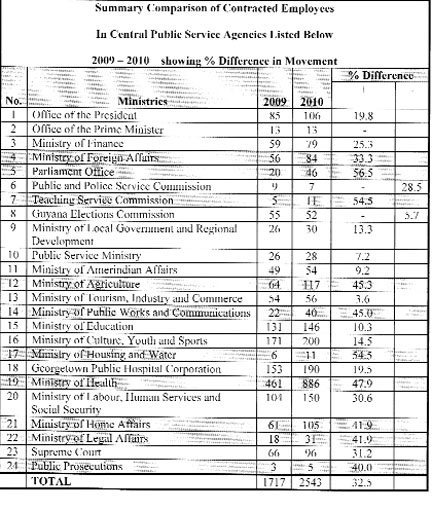

On reflection it may well be more than coincidence that resort has been taken increasingly by public service agencies, to employing personnel (qualified and unskilled) on contract. At the time of writing the 2011 National Budget was not seen, but analysis of the 2010 version revealed the following scenario regarding contract employees in the public sector.

However the actual number of authorised positions is no longer made available in the National Budget.

One amongst several implications of this development is the transient nature of the relationship between employer and employee. Another is that so far as traditional public service positions are concerned there is little or no consistency in the value offered for the same job. The ‘discrepancy’ can be even more discernible in autonomous public sector agencies.

The whole series of transactions bypass the Public Service Commission, with no effective substitute monitoring mechanism in place. In any case the nature of contract employment tends to preclude longevity of service, and concomitantly the promotional and developmental aspects of employees; as well as to discourage the retention of critical institutional memory.

The concerns therefore for the future stability (and productivity) of the public service are numerous (including talk of licensing teachers – a critically scarce skill).

It is questionable how many contracts include a productivity provision on which basis a gratuity of 22.5% is paid on basic salary, usually semi-annually. (The equally qualified traditional public service counterpart doing the same or similar job, is offered 5% annually and is subject to a code of discipline that can in extreme circumstances preclude normal retirement and related benefits even after extended service).

At the same time there have been reports that contracted employees are not necessarily excluded from the annual across-the-board dispensation; and egregiously enquiries have been made about eligibility for further superannuation benefit in respect of a minimum of ten years’ service as a contract employee.

Given the aforementioned irregularities in individual agencies and the inconsistencies across public sector organisations in salary administration, it would be interesting to conduct a survey of trends. While for example employers in developed countries are known to have argued that older workers are more costly, indications are that the obverse of the situation may obtain in our context, since, as alluded to earlier, such a disproportionately high percentage of long service employees remain compressed at the minimum of the related salary scales. It is this category of ‘senior’ employee who must perforce stay in place when the high-flying ‘contracted’ counterpart, sooner than later, converts to being a frequent flyer who demits employment on notice, and with pre-paid gratuity. This is not to deny that the very fact of being a high-flyer indicates a logical movement towards better qualifications and more rewarding careers, most times available only outside our borders. This type of mobility is regularly reflected in the private banking system, where the faces of young bright cashiers change at a rapid rate.

The sugar industry is also an outstanding example of an organisation sorely afflicted by the loss of institutional memory and experienced skills.

In a society which takes pride in its progressive achievement in improved health standards and the quality of life generally, there lies a contradiction in subverting that very healthy citizen by the peremptory termination of productive years of service, and, in too many cases, to languish in an enforced indisposition which may in turn have to be medically treated. The almost insignificant number of terminees who may subsequently gain access to the diaspora and there thrive further in unpredicted ways, belies the perceptions of their utility at home.

Notwithstanding the above, a quick review of a sample of public sector entities and constitutional agencies reveals variations in their retirement policies. For example:

a) Institutions like the GRA and the Audit Office, with the approval of government, have converted to a pensionable age of 60 years, based on an employer/employee contributory pension agreement.

b) Guyana Sugar Corporation observes a retirement age of 60 (but still has to rely on retirees to operate in strategic areas).

c) Guyana Shipping Corporation observes a similar retirement policy as GuySuCo, as does Guyana National Printers Ltd.

The Guyana Defence Force is reported to have its unique dispensation in respect of retirement. There is reason to believe that at least one public sector agency has a retirement mark of 65 years – the same as the retirement age of public servants in Barbados.

One argument mooted against raising the pensionable age of public servants, including teachers (one is uncertain to what extent doctors in the public sector are affected), is that it stifles promotion – a proposition which does not withstand scrutiny on two counts:

i) that the young generation of entrants are employed on contract;

ii) that the significant percentage of substantive vacancies in several agencies have remained unfilled as a matter of policy, complemented by a significant incidence of acting appointments.

One would have thought that since the sure source of NIS contributions rested within government employment, the fund would benefit from assured contributions over the five years between 55 and 60, of which it is now largely deprived. Why should this category of employee be treated less favourably than any sugar worker – who formally retires at 60?

Yours faithfully,

E B John