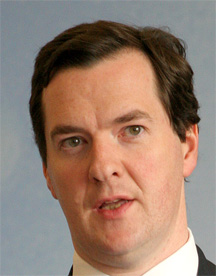

On March 24, Britain’s Chancellor of the Exchequer, George Osborne, made a long awaited announcement about the future of Britain’s controversial Air Passenger Duty (APD), the discriminatory tax that charges those travelling out of the UK more to fly to the Caribbean than to the west coast of the United States. Although he offered no immediate relief for the region, he specifically acknowledged in relation to the Caribbean, the illogicality of the tax.

Speaking to the British Parliament, Mr Osborne said the he and his party’s coalition partners had hoped to replace APD as a per passenger tax with a per plane tax, but having tried every possible option had reluctantly had to accept that such an approach was currently illegal under international law. While the UK would, he said, now work with other governments s to try to have the law changed in the longer term, it would in the meantime launch a consultation on how to improve the existing system.

Speaking to the British Parliament, Mr Osborne said the he and his party’s coalition partners had hoped to replace APD as a per passenger tax with a per plane tax, but having tried every possible option had reluctantly had to accept that such an approach was currently illegal under international law. While the UK would, he said, now work with other governments s to try to have the law changed in the longer term, it would in the meantime launch a consultation on how to improve the existing system.

In a welcome recognition of the difficulties the UK has created for a region as tourism dependent as the Caribbean, he specifically referred to the existing “rather arbitrary bands that appear to (have us) believe that the Caribbean is further away than California.”

His announcement, however, had a sting in its tail. For while he launched a consultation document making clear that the UK was looking to review the structure of its existing banding system, the Chancellor also stated that he would “delay this April’s Air Passenger Duty rise to next year.” This announcement, which seemed to suggest consideration was being given to an April 2011 increase, despite swingeing increases as recently as November last year, made clear that the UK now regards APD as a significant, permanent, long term source of general revenue increasing annually at least by the rate of inflation.

What the UK is now suggesting in the accompanying forty-six page consultative document are two changes to as it says “minimise market distortions.” It proposes simplifying the existing regime in one of two ways. The first would involve reverting to a two band system divided by class of travel. This model would divide short haul and long haul travel within a delineated boundary. Short haul would be based on the European Union/European Economic Area/European Civil Aviation Area and long haul, the rest of the world. This would recognize that the greatest emissions come from the more travelled and consequently environmentally less friendly routes in the European area. It would also avoid the discriminatory nature of the present system.

The UK government’s second option seeks to create greater differentiation within the long-haul sector by introducing three distance tax bands and two classes of travel. This draws boundaries around 2000, 2000 to 4000 miles and beyond 4000 miles.

The document also seeks views on how the existing class of travel distinction might be changed in revenue neutral ways that are administratively simple. It asks for suggestions for an alternative approach that might enable a case to be made for significantly lowering the tax burden on Premium Economy, a class of travel particularly popular for visitors to the Caribbean from the UK; and suggests that executive jets will be brought within the scheme.

For its part the Caribbean has given a cautious welcome to the Chancellor’s statement. The Chairman of the Caribbean Tourism Organisation, Ricky Skeritt, who is also the Minister of Tourism of St Kitts-Nevis, welcomed the UK Chancellor’s statement as “a clear recognition of a crucial issue that has been the focus of the strong lobbying efforts by the CTO and its allies in the private sector, the Caribbean High Commissions, and the Diaspora.” He also welcomed the fact that that Air Passenger Duty will not rise in 2011, “increasing the current tax burden on British travellers to the Caribbean.”

He cautioned, however, that while this was a small but important victory for the Caribbean offering clear evidence that the British government is listening to the region’s concerns, the Caribbean would, he said, in the coming weeks, continue to argue that the current banding system places the Caribbean at a disadvantage and hurts its economies. “We will persist in our efforts to obtain a fairer system of aviation taxation that does not cripple travel to our heavily tourism-dependent region.”

“Our advocacy on the APD is not over,” he stressed. “All Caribbean tourism interests must continue to fight for APD reform in a manner that further removes any competitive disadvantage, and does not hamper our efforts to achieve sustainable growth in tourism, for the benefit of the people of the Caribbean.”

In many respects the first of the two options the UK has suggested is similar in structure and intent to the approach the region proposed last October. However, the Chancellor’s consultative document contains some worrying elements as it suggests that taxation or other forms of levy are set to rise and rise.

In the consultative document the British government suggests that its proposed options would have the attraction of refocusing APD on “its core objectives of raising revenues for the Exchequer in a simple, fair and efficient manner, whilst recognizing that the Government’s goals for limiting global missions from aviation are primarily to be delivered through international mechanisms such as the EU ETS, and that local aviation emissions are best addressed through other policy levers.”

What the UK appears to be suggesting is that its approach offers a way of separating over a short period APD as a fiscal measure from its alleged link to aviation emissions, by running APD and the EU’s Emissions Trading Schemes in parallel. In other words, APD will be a fiscal measure subject to regular increases and EU ETS will function as the emissions scheme levied on travellers through licences sold to the airlines.

Caribbean tourism ministers demonstrated in Brussels two weeks ago, anything that touches the fortunes of an industry that accounts for up to 1 in 4 jobs will impact on the lives of the general population. The UK is an important source market for tourism in the Caribbean, for example providing Barbados with around 38 per cent of total stop-over arrivals.

The Chancellor’s failure to address the Caribbean anomaly looks set to result in an increasingly difficult dialogue between the UK and the region.

Previous columns can be found at www.caribbean-council.org