Dear Editor,

Some years ago a study was conducted of traffic accidents in Latin America and the Caribbean. The data showed that, for instance, Brazil with one-third of the total population and vehicles, suffered one-third of the fatalities. The study reported at the time that Brazil’s National Highway Department estimated the average cost of injury accidents at US$1,500 – including the loss of future income, vehicle damage, medical and hospital costs, and damage to cargo.

Traffic accidents were categorized under ‘Urban’ and ‘Rural’ and were seen as a public health problem, in which the age range of victims was taken into account. Indeed the number deaths by traffic accidents was registered by the Ministry of Health. Notwithstanding the usual blame placed on human error, it reported that other studies in Brazil (and in other countries) had shown that “inadequate conditions of vehicles; signs and signals; and construction and maintenance of roads and sidewalks; were also contributory factors to many accidents.” The view expressed therefore was that “the number and severity of accidents can thus be reduced by improved traffic engineering… with or without improved behaviour of people in traffic.”

The argument made was as follows: Investments in traffic engineering have two strong points:

i) the results are immediate and can be traced to the measures implemented.

ii) the results are usually long lasting and do not required continued presence of human resources.

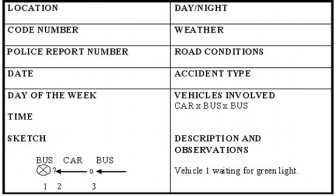

The study suggested that critical support for traffic engineering to reduce accidents was the establishment of a databank produced from police accident reports which should routinely include the following: date, time and location; basic data about the vehicles involved; data about the people involved; identification of witnesses; some description of the accident (text and/or sketch); physical/mental state of driver(s) involved; mechanical state of the vehicles involved; auxiliary data about weather conditions, the road(s), signs, signals and road markings, at the time of the accident; and preliminary evaluation of the seriousness of injuries sustained by victims.

A typical Accident Data Sheet (which can be completed manually) is shown at Exhibit 1.

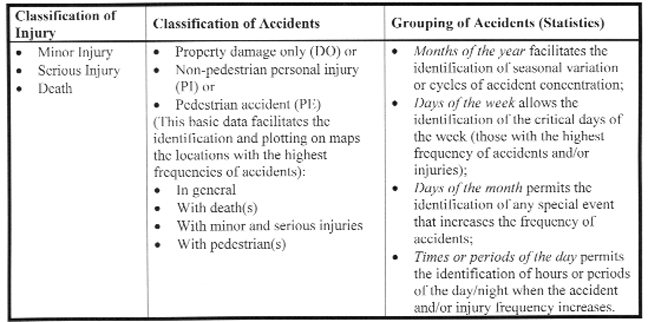

The study suggested further the collection of information based on the following matrix at Exhibit 2:

There are other detailed contributing factors to accidents which the study addressed, but the above should appear to provide our stakeholders sufficient food for thoughtful digestion.

It is against this informed background that we in Guyana, who are not yet dismembered, should feel compelled to consider appropriate, though belated, action so far as our own dangerous situation is concerned.

Increasingly over recent years the twin problem of traffic control and transportation management has been identified as impacting on the life of every adult or child who is required to utilise the nation’s roads. With the tremendous and continuing increase in the volume of traffic on virtually the same mileage of roadways over the last 10 years say, the prospect of death or serious injury by vehicular accident becomes more certain. The impact on the quality of life is fearsomely negative. The accident rate per road mile continues to raise alarm amongst all concerned citizens. Much of their official effort however has been limited to exhorting commuters to do and behave better. Little in fact has been done to curb the rampant violation of traffic laws and the consequent decimation of lives and limbs. Amidst the exhortations by some, therefore, copious tears are being shed by others.

The fact is that there appears to be no coherent plan of action to deal with a problem that can only worsen. One reason for the non-existence of a plan is the lack of any articulated vision of the future physical development of, for example, Greater Georgetown, its environs and its road linkages. If at all anything has been undertaken, little is known, for instance of any effort to investigate and analyse the effects of large and heavy container-type traffic on the sustainability of our roadways. At the other end of the transportation spectrum is the alarmingly uncontrolled revival of the ‘donkey cart’ (without traffic signals or brakes) galloping through (non-operational) traffic lights.

There can be little argument that a transport plan for Guyana is an urgent priority. While many concerned groups, individuals and institutions have voiced their anxieties from time to time, it is now absolutely imperative that we have ready a coherent plan for the management of transportation, for this and the next millennium.

The list of perceived issues include, but are nor limited to, the following:

road engineering for safety; traffic speed control; parking; licensing of vehicles, drivers; vehicles inspection; used tyres; general vehicular statistics; traffic signage; motor vehicle legislation.

The above and related issues would appear to justify the convening of all identified stakeholders who will examine the inherent problems, recommend solutions, as well as introduce new innovative ideas that would eventually cohere in a strategic plan to manage and control traffic on our roadways.

Stakeholders should include: Commissioner of Police and officials of the Traffic Department; National Road Safety Council; members of the Bar Association; Guyana Medical Council; Insurance Association; Private Sector Commission; Shipping Association; trade unions; Consumers’ Association; Guyana Revenue Authority; the media; private sector road engineers; minibus owners and drivers; taxi owners/drivers; Mayor and City Councillors; other mayors and representatives of selected local government authorities; Ministry of Education; Guyana Teachers’ Union; Ministry of Works and Communication; Ministry of Labour – Occupational Health and Safety; Guyana National Bureau of Standards; civic organizations.

With the approval of the Minister of Home Affairs, the National Road Safety Council should be tasked with organising this convocation.

Yours faithfully,

E B John