Easter is one of the most important religious festivals for Christians and the second in magnitude of the two very prominent ones with extensive public appeal (the first of these is Christmas).

It is associated with public exhibitions, although relatively subdued today and confined to the church, but in a large way is partly responsible for the rebirth and development of western theatre. There are also traditional enactments and minor festivals derived from Easter as well as the large store of poetry inspired by it, ranging from the religious to the revolutionary and the Caribbean.

The Roman Catholics perform a street procession which is a ritual and a dramatization of Christ’s journey to Calvary bearing the cross, but there have been larger performances, and in the Middle Ages the beginnings of Easter performances were also the rebirth of western drama. Liturgies which turned into liturgical drama were read by priests in masses and turned into dramatic pieces performed there, expanding into larger rituals and into the formation of plays. These were the passion plays which dramatized the crucifixion and started a tradition which is still known today. But the passion plays written by priests for the benefit of the parishioners eventually outgrew the church and became the property of the townspeople, leading to popular performances and the evolution of more secular theatre.

The Roman Catholics perform a street procession which is a ritual and a dramatization of Christ’s journey to Calvary bearing the cross, but there have been larger performances, and in the Middle Ages the beginnings of Easter performances were also the rebirth of western drama. Liturgies which turned into liturgical drama were read by priests in masses and turned into dramatic pieces performed there, expanding into larger rituals and into the formation of plays. These were the passion plays which dramatized the crucifixion and started a tradition which is still known today. But the passion plays written by priests for the benefit of the parishioners eventually outgrew the church and became the property of the townspeople, leading to popular performances and the evolution of more secular theatre.

The story of the crucifixion became the core of many rituals over the centuries. There is powerful symbolism and metaphorical possibilities in the Christian mythology and the concept of the self sacrifice of the son of God. Many of these may be found in Catholic Latin America. Wilson Harris based his novel Companions of the Day and Night on the ancient posada ritual of Mexico which has the mixture of a ‘pagan’ rite with mas/masquerade, the dramatization of a passion play, the idea of sacrifice and an actor taking up the role of the Christ figure by which he is possessed.

The same story has inspired a great deal of literature including drama. Michel de Ghelderode, Belgian twentieth century avant garde dramatist most famous for the play Escurial about the tension between the absolute royal power of a king and the alternative power of his ‘fool’ (a court jester with satirical privileges), wrote Barabbas with a more heroic portrayal of Easter’s well known felon. In Jamaica, playwright Easton Lee wrote the very popular Lenten drama The Rope and the Cross often performed around the Caribbean. The same theme was taken up in one of the most famous choreographies in the repertoire of Rex Nettleford’s NDTC, The Rope and the Cross a duet first danced by Sheila Barnett in 1974. The NDTC is revisiting it among many other performances today in their annual Easter Sunday performance at The Little Theatre in Kingston. The ‘Morning of Movement and Music’ sees Keita-Marie Chamberlain and Tamara Noel performing the duet as well as other works by Barry Moncrief (current artistic director of NDTC) and Bert Rose.

Related to these performances is the occasional performance by Mervyn Morris of his very famous sequence of poems in the dramatic collection On Holy Week. Morris is only one of the many poets influenced by the Easter story with its accompanying mythology, powerful symbolism and thematic concept. These poems range from the religious to a variety of other interests drawn in by the poets.

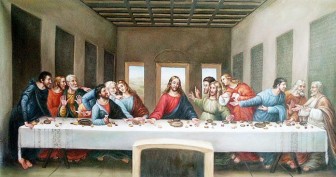

English poet and artist (engraver) William Blake was a Christian writing in the late eighteenth century and is often described as the first romantic. Although deeply religious he was known for his critically anti-Christian poems because of his deep resentment of the way Christians practised Christianity in the London of his time. His poem “Holy Thursday” is an unholy document of unchristian hypocrisy and inhumanity, with an ironic ring to the title “holy”. For Christians the Thursday before Good Friday has special significance because of the events in the life of Jesus, including The Last Supper, that took place on that day which is called Holy Thursday. The power of the Easter inspiration is also to be found in the fine arts, most famously in one of the most revered paintings of history, the Renaissance work ‘The Last Supper’ by Leonardo da Vinci. (Incidentally, researchers have only last week announced that they have unearthed evidence which suggests that the “last supper” actually took place on the Wednesday of Holy Week, and not Thursday as was always believed.)

Other poets have used the Easter theme in various ways to explore other preoccupations. WB Yeats, for example, wrote “Easter 1916”, a poem that is not concerned with the religious festival at all. It describes the “Easter rising” in Dublin which took place at Easter in 1916 and was an important event in Ireland’s violent struggle for independence from Britain. It is that poem with the significant line “a terrible beauty is born” which talks about the revolutionaries who occupied key locations in Dublin to wage war on the British. Some of them were the poet’s friends or acquaintances who he never thought of as revolutionary or heroic. Yeats saw in this a different kind of sacrifice and hinted that the experience taught him to be a better poet, and actually became involved in the struggle for an Irish nation although he despised the violence.

An even more famous poem is “Journey of the Magi” by TS Eliot, sometimes referred to as a Christmas poem. But it has as many images and references to Easter as it has of Christmas, yet is not a religious poem at all. It discusses the birth of Christ from the point of view of an outsider, a king from the East, one of the Magi who journeyed to meet Jesus at his birth. The narrator is an unbeliever, who eventually discovered that he was actually touched by his experience and the nature of his kingdom and the lives of his people had changed. But Eliot charges the poem with many allusions to the story of the crucifixion as the narrator keeps repeating his confusion with the notions of “birth” and “death” which run throughout the poem. Easter is supposed to be about rebirth and new life given to mankind by the self-sacrificial death of Jesus, the incarnation of God who came to earth for that purpose.

Caribbean poet Mervyn Morris has produced another example of this kind of play on the Christian theme deliberately confused with a number of other non-religious concerns of the poet. On Holy Week is the best known Caribbean Easter verse, but Morris executes a pun in the title which when pronounced sounds very much like “Unholy Week”. This is reminiscent of Blake in his concern for unholiness in the church which he criticized. Morris is quoted by the Jamaica Observer newspaper as saying that many religious persons have quoted from his poems in the Easter collection, but as many have avoided them where they would not have approved of what is expressed.

The paper also quotes Morris as saying that the real inspiration for writing the sequence of poems actually began with Pontius Pilate. Morris was an administrator at the time and felt that Pilate has been very much misunderstood. He is always portrayed as the villainous administrator who ordered the crucifixion and then washed his hands. (This is the source of the well used expression of someone “washing their hands” of a particular matter that they want to be finished with and forget). But Pilate was actually trying very hard to save Jesus. Morris dramatizes the Easter story in a way that makes it his, and very Jamaican. That is worthy of its own more detailed study.