MEXICO CITY, (Reuters) – Once praised lavishly by the United States for waging a war on drugs, Mexico’s last two presidents now say legalizing them may be the best way to end the rising violence the U.S.-backed campaign has unleashed.

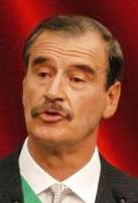

Ernesto Zedillo and Vicente Fox led efforts to crush drug trafficking gangs in Mexico between 1994 and 2006 but the rapid escalation of violence over the past four years under President Felipe Calderon has convinced them a change of tack is needed.

“As a country, we are going through problems due to the fact that the United States consumes too many drugs,” the 68-year-old Fox told business leaders in Texas last month. “I would recommend to legalize, de-penalize all drugs.”

Though public support for some legalization is growing on both sides of the border, resistance is firmly entrenched in the U.S. government and analysts say Mexico is very unlikely to liberalize its drug laws without Washington’s approval.

Calderon is stuck between a rock and a hard place.

He has staked his reputation on breaking the cartels and is unlikely to press for radical change in what remains of his presidency but the death toll is surging and Zedillo, Fox and other former Latin American leaders are pressuring Mexico to consider opening up the market.

Victims’ families are adding to the clamor for change.

Calderon has begun to soften the hard-line rhetoric that won him allies in Washington, stressing his readiness to discuss the merits of drug legalization.

“I’m completely open to this debate. Not just on consumption, but also on movement and production,” he told a meeting with victims’ families in Mexico City on Thursday.

But he added: “This issue goes beyond national borders. If there’s no international agreement, it doesn’t make sense.”

Since he sent the army to fight the cartels in late 2006, some 40,000 people have died. If the rate of killing persists, the total will surpass U.S. combat deaths in the Vietnam War by the time a new president is elected in mid-2012.

The United States was still fighting in Vietnam when President Richard Nixon first declared a “war” against drug trafficking and consumption. Forty years on, more and more statesmen who have followed its course say the fight against the cartels cannot be won by force either.

Zedillo was among the former Latin American leaders on the Global Commission on Drug Policy which this month concluded the drugs war had failed, urging Mexico and others to explore regulation as a means of weakening the criminal gangs.

New rackets

Calderon insists his strategy has weakened the cartels and that the capture of many prominent drug bosses has reduced the threat that organized crime posed to the state.

But the violence has shocked many Mexicans and hit support for Calderon and his conservative National Action Party, or PAN. Polls suggest the PAN will be ousted at the presidential election in July, 2012 by the opposition Institutional Revolutionary Party, or PRI.

The PRI has pilloried Calderon for the growing lawlessness, though it has yet to offer any radical alternative to defeating the drug gangs, whose interests during the crackdown have grown to encompass a host of new rackets.

The expansion of criminal activity has even prompted those who back decriminalizing soft drugs — such as Mexico’s Green Party — to question how much legalization would achieve.

“Do you think the drug bosses will suddenly turn into normal businessmen? Of course not, they’ll just turn to other sorts of crime like robbery, kidnapping and extortion,” said Arturo Escobar, a member of the Greens in the Senate.

Mexicans have long been skeptical about legalizing drugs but the country has decriminalized possession of small amounts of soft and hard drugs under Calderon, and sympathy for a more liberal tack has grown as the violence intensifies.

A national survey in August 2010 by daily Reforma showed 32 percent of Mexicans in favor of legalizing personal use of marijuana. Barely two years earlier, in October 2008, support for legalization was just 7 percent, pollster Parametria said.

Support in the United States now stands at 46 percent, according to a Gallup poll published on Oct. 28.

Yet despite support from some libertarians, a recent shift to the right in U.S. politics has made it tough to sell the idea before a 2012 presidential vote in both countries.

“If Mexico legalized, the U.S. Congress would use every piece of pressure it has to oppose them,” said Rodolfo de la Garza, a political scientist at Columbia University. “We will hit them economically. We will start messing with NAFTA. We will hammer them on migrants. Much more than we are already.”

Drug demand is driven by the United States, and Fox this month stepped up calls for legalization, arguing that Washington’s $1.4 billion in drug war aid was nothing but a “tip” in compensation for Mexico’s losses in the war.

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime says the global drugs trade is worth hundreds of billions of dollars and in 2009 a top official at the agency said traffickers’ cash had helped prop up the banks during the financial crisis.

Legalizing drugs would generate some $88 billion a year in savings and tax revenue for U.S. federal and state governments, according to Harvard University economist Jeffrey Miron.

As long as public budgets remained stretched, pressure is likely to grow on governments to regulate the market, said Daniel Okrent, the author of “Last Call – The Rise and Fall of Prohibition,” a study of the era of U.S. alcohol prohibition.

“Prohibition ended because of The Depression. The federal government was in desperate need for cash and the country needed jobs,” said Okrent. “This and the unwillingness to pay taxes is one of the reasons why there will be legalization.”