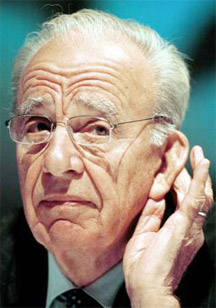

When I first read that media mogul Rupert Murdoch had closed down his sensationalist British tabloid News of the World, my first reaction was, “Good riddance!” But I’m no longer rejoicing — the scandal around the now defunct daily’s unscrupulous journalism will encourage government controls of the media worldwide.

I can already see Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez, or Ecuador’s President Rafael Correa, or other demagogues in Latin America, the Middle East and other parts of the world saying, “If the British government is considering stronger mechanisms to control media excesses, why shouldn’t we?”

In fact, since it was first reported that Murdoch’s News of the World had engaged in apparently illegal wiretaps, bribes and other shady tactics to beat its competitors, British Prime Minister David Cameron and other key opinion makers have called for new systems to control illegal activities by the media.

Cameron said that that Britain’s Press Complaints Commission, a self-regulatory body funded by media companies, “has failed,” and “lacks public confidence.” The prime minister, who is under fire at home for his cozy ties with Murdoch’s media empire, is proposing to replace the PCC with an external commission that would be independent both from the media companies and the government.

Cameron said that that Britain’s Press Complaints Commission, a self-regulatory body funded by media companies, “has failed,” and “lacks public confidence.” The prime minister, who is under fire at home for his cozy ties with Murdoch’s media empire, is proposing to replace the PCC with an external commission that would be independent both from the media companies and the government.

Janine Gibson, editor of The Guardian, the newspaper that led the investigation into News of the World’s dubious practices, wrote that the PCC failed largely because “its paymasters,” the newspaper publishers, didn’t demand that the commission hire a credible outside inquiry into the Murdoch newspaper.

“There is too large a concentration of power at the heart of the newspaper industry — and patently too weak a sense of purpose, for this [self-regulatory] system to work,” she wrote. Gibson proposed creation of “an independently licensed body… funded, but not in any way answerable to government” to replace the PCC.

Some US media analysts, including Juan Cole of the University of Michigan, have been quoted as supporting a return to the fairness doctrine, a US Federal Communications Commission policy that required radio and TV stations to present controversial issues in a manner the commission would view as honest and balanced. The 1949 policy was discontinued in 1987.

In Latin America, in addition to Cuba, which makes no bones about state censorship of the media, Venezuela passed media law in 2004 that allows the government to monitor the content of radio and television stations. Ecuador is about to pass a government-sponsored law that would create a regulatory commission to supervise both electronic and print media.

The Ecuadorean press bill may be the worst in Latin America, with the exception of Cuba. Correa, Ecuador’s populist president, has repeatedly called for a new law “to avoid excesses of the media,” after leading newspapers published documents showing that his brother Fabricio Correa had obtained contracts worth more than $300 million from his government.

Correa held a wide-ranging national referendum on May 7, and — by including his controversial media control proposal amid several other more popular plans — succeeded in winning a mandate to pass his media bill.

Ricardo Trotti, head of the press freedom project of the Inter American Press Association, told me in a telephone interview from Quito, Ecuador, where he was on a mission last week, that the bill is almost sure to become law shortly. It will create a seven-member media monitoring commission, most of whose members will be directly or indirectly appointed by the government, he said.

“The danger is that this commission will be able to punish the media, and could allow the president to interfere with editorial content,” Trotti said. “We think that the best way to regulate the media is to make it subject to the same general laws that apply to all members of society.”

My opinion: I agree. If Murdoch’s newspapers engaged in illegal wiretappings, bribery or other illegal activities, these actions should be punished with the same laws that criminalize such behaviour by any other citizen.

The alternative — creating special press regulatory commissions — may or may not work in Britain and a few other countries with strong democratic traditions, but will almost surely be used in the rest of the world to justify new — and more stringent — controls on the press. It’s a risky road that is likely to do more harm than good.

© The Miami Herald, 2011. Distributed by Knight Ridder/Tribune Media Services.