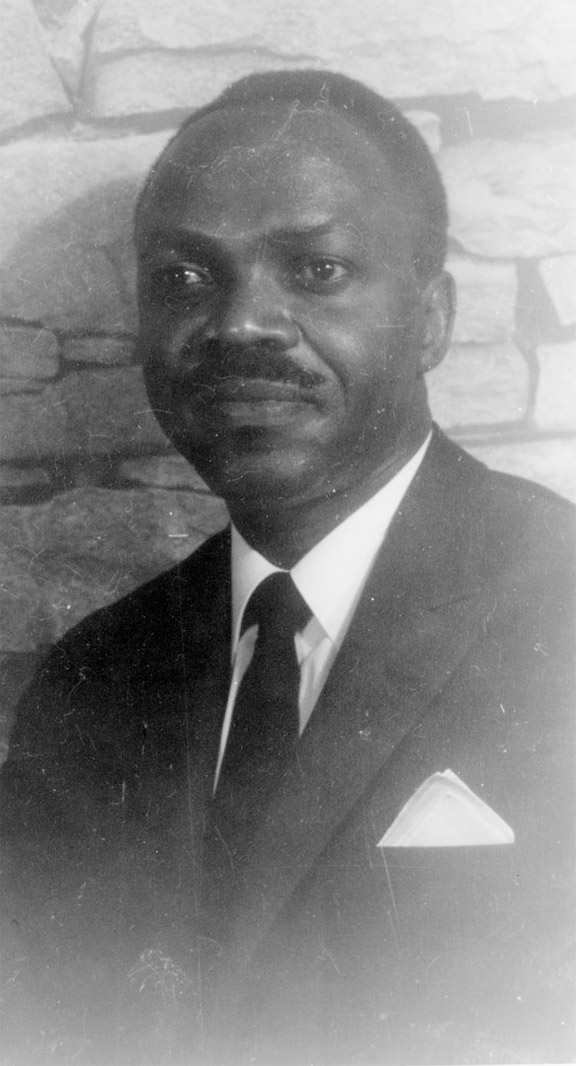

Edward Ricardo Braithwaite is a Guyanese novelist and scientist who served as writer, teacher and diplomat during his long career. Alim Hosein, who researched his life, points out that there are different dates provided in different sources about his birth, so it is not widely known that he was actually born on June 27, 1912. He is currently living in Washington DC.

ER Braithwaite, as he is known, came from a privileged family, which may be confirmed by the fact that he attended Queen’s College in Georgetown, and for a black student in those years, that, and his higher education suggest privilege indeed. According to an internet source, he grew up “surrounded by education,” moving on to Cambridge University and a doctorate in physics. Like so many colonials in the former British Empire, he served in World War II, but his later career as a writer does not reflect the mind of a colonial, but was driven by far more radical sentiments including a consistent resistance to colonialism and the ‘othering’ treatment accorded to minorities.

While he did write scientific texts, it was his literary career that brought him to prominence and his best known contribution is that which he made to literature and film. He served his country, Guyana, in diplomatic posts, at UNESCO, as Perma-nent Representative to the UN and Ambassador to Venezuela. His reputation made him very distinguished in literary circles as an academic, Writer in Residence, with literary attachments and Visiting Professorships at New York University, Howard and Manchester Community College, among others.

Among his literary publications are To Sir With Love (1959), Paid Servant (1962), A Choice of Straws (1965), Reluc-tant Neighbours, A Kind of Homecoming and Honorary White (1975). While it was the Hollywood film made from his first novel that rocketed him to fame, he can claim a contribution to literature in his own right. This involves his joining writers and workers ‘in exile,’ a major movement of migration which led to the international rise of West Indian literature among the ‘exiles’ in London in the 1950s, so closely associated with Caribbean Voices (of which he was not a part).

Among his literary publications are To Sir With Love (1959), Paid Servant (1962), A Choice of Straws (1965), Reluc-tant Neighbours, A Kind of Homecoming and Honorary White (1975). While it was the Hollywood film made from his first novel that rocketed him to fame, he can claim a contribution to literature in his own right. This involves his joining writers and workers ‘in exile,’ a major movement of migration which led to the international rise of West Indian literature among the ‘exiles’ in London in the 1950s, so closely associated with Caribbean Voices (of which he was not a part).

But Braithwaite wrote from his experiences in Britain and other societies where racial discrimination against ethnic minorities existed. The foundation writers recorded the Caribbean experience at home and the realities of exile which contributed to the powerful fiction that developed inspired by these forces. Braithwaite made his contribution to the part of this fiction preoccupied with the black experience in Britain, following his namesake Edward Brathwaite, better known as Eddie and Kamau, Sam Selvon, and George Lamming. David Dabydeen was to take this up in a later generation, although approaching the black British experience from different angles and realities. Of note is the work of another Guyanese novelist in London who wrote Black Teacher arising from her experiences in the 1950s when she was, according to her account, one of the first black teachers in the English school system. Braithwaite continued on this note, extending his concerns to other social areas in London.

But Braithwaite wrote from his experiences in Britain and other societies where racial discrimination against ethnic minorities existed. The foundation writers recorded the Caribbean experience at home and the realities of exile which contributed to the powerful fiction that developed inspired by these forces. Braithwaite made his contribution to the part of this fiction preoccupied with the black experience in Britain, following his namesake Edward Brathwaite, better known as Eddie and Kamau, Sam Selvon, and George Lamming. David Dabydeen was to take this up in a later generation, although approaching the black British experience from different angles and realities. Of note is the work of another Guyanese novelist in London who wrote Black Teacher arising from her experiences in the 1950s when she was, according to her account, one of the first black teachers in the English school system. Braithwaite continued on this note, extending his concerns to other social areas in London.

He wrote of the plight of ethnic minorities, like Beryl Gilroy’s black teacher. In fact, he was pushed into literature by his own experience which was similar to Gilroy’s as a teacher. The difference is that Gilroy was a teacher by chosen profession; Braithwaite got into it by forced circumstance. Hosein captures the initial situation neatly: “After the war like many other ethnic minorities, Braithwaite could not find work in his field despite his extensive training. Disillusioned, he reluctantly took up a job as a schoolteacher in the East End of London where he worked for 9 years.”

This resulted in the fictionalising of his encounter with hard-to-handle East End students in To Sir With Love. According to an internet source, another commentator who claimed to have been there at the same time with Braithwaite, claimed after the publication, film and fame, that those events never happened and Braithwaite’s account is inaccurate. But apart from the fact that no one took this on, it does not seriously matter where the purpose of fiction is concerned. Those conditions drove Braithwaite in his later works to a continued desire to attack the horrors of discrimination, apartheid, and horrendous social realities which he took up in Choice of Straws. Hosein also drew attention to a comment taken from The Daily Telegraph by Guyana’s National Library, about Reluctant Neighbours: “His brilliant exploration of racial prejudice is from the unusual angle of the successful black man.”

This links with Hosein’s own observation that, “What is noteworthy about his work is the way in which he avoids bitterness or rancour. He wrote about the difficulties he saw and experienced without losing an essential humanness. Without outright condemnation or attack, he was able to expose discrimination. He not only exposed discrimination by Whites against Blacks, but also discrimination by better-off Whites against poorer Whites.”

Braithwaite’s concern for these horrendous social realities extended to the conditions among white East Enders generally. As a privileged, successful black man he was able to widen his perspectives to a more universal concern for humanity, which strengthened his contribution to literature.

But there is also his contribution to film. Film helped to make him world renowned. The BBC dramatised both To Sir With Love and Paid Servant. “While writing his book about the school, Braithwaite was seconded to the Department of Child Welfare to work with the immigrants who were, after the war, moving into England. Among his responsibilities was finding foster homes for non-white children for the London County Council. His experiences in this field led to Paid Servant (1962).” The impact, however, was made by the major mainstream cinema version of To Sir With Love with Sidney Poitier in the lead and the theme hit song by Lulu.

The contribution to film lies in the context of Hollywood’s interest in the novel and the way it allowed the book’s concern a much wider audience, which also meant a gain for the cinema’s treatment of black issues and the condition of the underprivileged. Hollywood would have been drawn to it by the marketability of the conflict, the unconventional love interest, the ethnic issues concerning a black teacher pitted against rough white teenagers, the urgency of race. Hollywood was still grappling with some of these factors in 1967. They were still trying to come out of ‘Blacksploitation’ involving the minority and the exploitative roles of black characters in the cinema to serious studies of blacks in the USA, then in Great Britain. These were still subjects of intrigue, including mixed race romances which had a long, hard time breaking into acceptance in cinema. Another point of reference is Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner also with Poitier.

These were all attractive to Hollywood, the romantic interest, the wild conditions in the East End of London, comparable with an American equivalent in Blackboard Jungle with Glenn Ford. These various interests created a kind of film that was not only conventional mainstream, but opened doors to a variety of other concerns and interests.

It widened the advance of serious treatment of blacks as major characters and the social situations that interested Braithwaite. The film also clearly widened his audience and reopened attention to his other works. This could only have strengthened the statements he wanted to make and established him as a universal humanist.

ER Braithwaite was celebrated in a programme staged by the National Library and chaired by Francis Quamina Farrier on May 21 last. Among other items was a dramatization of an extract from To Sir With Love acted by members of the Library with lead roles by Devon Ashby and fast rising, prize-winning actress and dancer Abigail Brower. The discourse on Braithwaite reproduced above, was presented there.