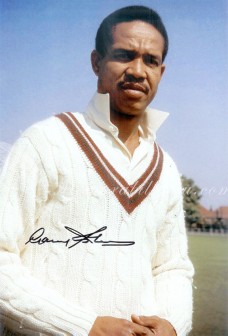

The “greatest cricketer on Earth or Mars” (as Sparrow extolled him in his 1965 calypso) passed another landmark last Thursday.

It was chronological, his 75th birthday, and it came as a timely reminder of the almost universal acceptance of the genius that made Sir Garry Sobers the finest all-rounder the game has ever known.

“Timely” and “almost” are words that would not have been necessary until just a few days earlier when the International Cricket Council (ICC) announced the All-time Dream Test XI, chosen by votes through its internet website from a supplied shortlist of candidates and designed to mark Test cricket’s 2,000th match, between England and Lord’s.

Sobers’ name did not appear. It was as if Pele was missing from a similar FIFA survey for football’s greatest.

ICC’s No.6 position went instead to India’s Kapil Dev, a worthy cricketer, no doubt, but no genuine comparison with the left-hander who Sir Neville Cardus, one of the game’s most eminent writers, once argued was “even more famous than Bradman ever was,” a reference to the prolific Australian batsman who occupies the ICC’s No.3 position as of right.

ICC’s No.6 position went instead to India’s Kapil Dev, a worthy cricketer, no doubt, but no genuine comparison with the left-hander who Sir Neville Cardus, one of the game’s most eminent writers, once argued was “even more famous than Bradman ever was,” a reference to the prolific Australian batsman who occupies the ICC’s No.3 position as of right.

At any time, such all-time selections in any sport are an exercise of futility and subjectivity, often founded on parochial bias. Statistics are a general, but unreliable, guide, if only because it is impossible to fairly compare players of different eras.

Even so, the exhibition staged by the Cricket Legends of Barbados to mark Sobers’ birthday last Wednesday provided a reminder of his remarkable record and emphasised the widespread disbelief at his exclusion from the ICC list.

By the time he ended a Test career that spanned 20 years, from 1954, when he was 17, to 1974 when 37, he had compiled more runs than any one else (8,032, average 57.78), held the highest score (365 not out), played more consecutive matches (85 out of 93 overall) and compiled more hundreds than anyone but the phenomenal Bradman (26 to 29).

He had also captained more times (39) and held more catches (109) than any other West Indian. Only Lance Gibbs had taken more wickets than his 235 except that Sobers had done so in three different styles.

By contrast, Kapil’s numbers in his time as India’s talisman from 1978 to 1993 were 131 Tests, 34 as captain, 5,248 runs at 31.05, 434 wickets at 29.64 (as swing bowler only, about the same pace as Sobers) and 64 catches.

So why would there have been such a palpable, indeed embarrassing, omission in a team to which the ICC gave its name? And there were a host of others through the 137 years of Test cricket’s existence who presented strong cases, if nothing nearly as compelling as Sobers.

Haroon Lorgat, the ICC’s chef executive, offered an explanation but it only went half-way.

“Selecting from such greats is no easy job, and not surprisingly, the selection mainly reflects modern players seen by present day supporters,” he said. “There are many greats from the past who would have easily merited selection in this team.”

Indeed, Bradman is the only one in the 11 who played before 1970 and he was surely not seen by present day supporters.

More to the point, as the Daily Telegraph noted, the vote “reflected the demographic of the electorate.”

In other words, the half-billion or so fanatical Indians, in India and the diaspora, with the inclination to get involved in the exercise and with access to the internet, significantly outnumbered those in any other Test entity, not least the West Indies.

It is a wonder there weren’t more than four Indians chosen, no surprise that there was not an Englishman in sight. At least, Brian Lara and Curtley Ambrose, made it.

But back to Sobers.

The Cricket Legends of Barbados used the function on Wednesday night to launch their DVD on Sobers’ life story, one in a series featuring the eight living “icons” of Barbados cricket (Sobers, Sir Everton Weekes, Wes Hall, Charlie Griffith, Seymour Nurse, Joel Garner, Gordon Greenidge and Desmond Haynes). The others will follow by the end of the year.

I must declare an interest for I was commissioned, along with Merville Lynch Productions, to put them together. The interviews with the greats themselves and with those who played with and against them were fascinating. The research was illuminating, if time-consuming.

Sobers’ tale of the rise of a boy from the Bayland, on the outskirts of Bridgetown, to teenaged prodigy, to “a gloriously vital and exciting cricketer” (Bradman’s description), to captain, knight and national hero is, truly, the stuff of legends. His work with Barbados tourism that goes back 30 years is, as he put it, simply a continuation of his contribution to the country of his birth.

There was one aspect of his cricket that I detected gave him as much satisfaction as any other. It was his attitude to the game and his fitness that explained his longevity that extended beyond his appearances for the West Indies to the captaincy of the Rest of the World in two series, in England and Australia, and Nottinghamshire in the English county championship, two record-breaking seasons with South Australia and several seasons in the leagues in England.

It was a physically punishing schedule yet there was a widely held perception that he paid little attention to practice, quite apart from being partial to the good things in life. It should have been clear that, as with any champion sportsman, Sobers’ God-given talent alone did not guarantee his success. The way he put it should be heeded by those who aim to follow his example.

He said: “The thing with a sport is to be in it and to prepare yourself to be in it. It’s not to want somebody to tell you what you do to get yourself fit. You get yourself fit.

“I used to swim a lot, I used to live at the beach and played a lot of beach cricket. I used to play cricket every day. I used to run. I played every sport because I knew how fit you had to be to play five days of a Test match.”

And on doing as much as he did on the field: “I enjoyed it because I was part of the game. I fielded close to the wicket because something was always happening. I couldn’t go out to deep third man or deep fine leg. I’d be lost, I’d be bored.”

The upshot was “18 years without once having to go off the field (with injury).”

And those were the days before physical trainers, physios and gyms.

Of course, he wouldn’t have to leave the field in the ICC All-Time XI. He would not get on it.