An assessment of the African presence in Guyana becomes topical annually around the time of the anniversary of Emancipation. Although Emancipation, its meaning, its cultural, social and political implications are much more universal and extend much further than manifestations of the African presence, this factor is an irremovable part of it. Its topicality assumes greater importance now because 2011 has been accepted as the International Year of People of African descent following the United Nations declaration.

But what is the African presence in Guyana? It finds itself in several different areas, sometimes highly visible or identifiable, but often hidden and always integrated (or diffused) into the general Guyanese culture. Very much of it is indistinguishable from what is ‘Guyanese,’ and what is Guyanese has within it much that derives from the nation’s African heritage. The reminder is pertinent that there is no one homogenous country called Africa. It is a vast continent with several different ethnic groups, languages and cultures, so when one speaks of ‘African culture’ the term is being very generally applied to the cultures brought with the enslaved captives to Guyana and the cultures that evolved among them in contact with a local environment.

We have often pointed out that too much of the African heritage in Guyana has faded or disappeared, but there remain elements that are strong and perennial. Several cultural traditions have gone, including many identifiable ones, and this is relevant to what is visible and what is sub-surface. Also, many others are diffused, reduced and subjected to acculturation, while yet others have been altered or evolved in a normal process of cultural change. One may investigate language, dress, food, music, religion, architecture, the popular culture, social, artistic, performance or theatrical traditions.

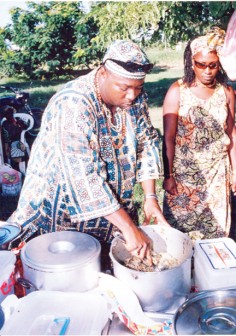

Not much will be seen in terms of dress, except at Emancipation time and on ceremonial occasions, since African dress is not common as normal Guyanese day-to-day attire. A few clothes items like the agbala, the dashiki, some female head-wraps and ‘skirt’ wraps are worn, and African print material is popular. It is not always clear, however, whether these are survivals or the contemporary influence of African clothing that has been imported either out of popular fashion or personal cultural choice. Only a small minority have made that personal choice. Within that only a very few individuals wear African clothing as their normal daily attire; prominent people who do this include Prof Jocelynne Loncke and Tom Dalgety. But an interesting item of Guyanese clothing is the shirtjac, which is of African influence and is often used as formal wear. Other persons in Guyana who shun the jacket and tie, will wear various forms of formal dress with this influence.

Not much will be seen in terms of dress, except at Emancipation time and on ceremonial occasions, since African dress is not common as normal Guyanese day-to-day attire. A few clothes items like the agbala, the dashiki, some female head-wraps and ‘skirt’ wraps are worn, and African print material is popular. It is not always clear, however, whether these are survivals or the contemporary influence of African clothing that has been imported either out of popular fashion or personal cultural choice. Only a small minority have made that personal choice. Within that only a very few individuals wear African clothing as their normal daily attire; prominent people who do this include Prof Jocelynne Loncke and Tom Dalgety. But an interesting item of Guyanese clothing is the shirtjac, which is of African influence and is often used as formal wear. Other persons in Guyana who shun the jacket and tie, will wear various forms of formal dress with this influence.

There is nothing that can be pin-pointed in terms of architecture, except what an expert technician or researcher may be able to tell us. Food is easier to identify, although such items that have survived since slavery or are exact dishes that can still be found in African societies are not the most popular or widespread. Many of these dishes now exist as ‘Guyanese food’ and they include African influenced items which are now known as ‘creole’ cuisine. Many of them include certain ground provisions, plantain and flour. Linguist Alim Hosein in a recent letter to the editor of Stabroek News, explained several different names and types of ‘bake,’ some of which are of apparent African influence or derivation.

Language in Guyana is an area where the African presence is deep, indelible and so much a normal part of speech that it goes unnoticed except to linguistics researchers, like Hosein who has a scholarly interest in it. Senior colleagues of his in the same field include Ian Robertson, John Rickford, Walter Edwards and George Cave. Almost on an annual basis English students at the University of Guyana go on field trips researching these elements and there should be quite a collection in store there. Guyanese Creole, popularly known as Creolese and Guyanese Standard English have substantial African components, which are so very influential in the creole that the latter evolved to the status of a language. There are several words and phrases of African origin, but what is more fascinating is that these linguistic features are not only lexical, but grammatical, syntactic and have also adapted African ‘linguistic concepts.’ Such ‘concepts’ exist in common Guyanese terms such as eye water, bottom-house, she run faas faas and it too sweety-sweety.

While it may be easy enough to believe that several vocabulary items are African or derived from African, it has been extremely difficult to convince Guyanese that their Creolese is a language in its own right, and not ‘broken’ English. It is so because of the way it is English-based, but it is different from Standard English in syntax, grammar and ‘concept.’ It is even harder to convince the population that there is such a thing as creole grammar and that Creolese has grammar. Most of these elements that make it different as a language are African elements.

Unfortunately, attitudes to the language are one of the factors of self-contempt that still exist in Guyana. People are generally ashamed of the creole, or look down on it and do not recognise it. The same goes for many other areas of African based culture. This has been partly responsible for cultural diffusion. It also helps to prevent the recognition of some strong survivals of the African ethos in Guyanese culture.

Among these is the use of theatrical and performance traditions. Africans move normally to the performing arts (and the visual arts, like sculpture; and the festival arts like costumes and masks) as expressions of almost everything including religion, rites of passage (moving from one state/stage of life to another: marriage, birth), mourning, medicine and social control.

It is a manifestation of the African presence when Guyanese use these performance traditions or oral literature for social control. Folk songs, folk tales (including Anansi), the faded/fading performance tradition known as Nansi Tori, (which is not to be confused with the trickster Anansi), proverbs, expressions of sexuality and kwe kwe (commonly written as queh-queh) have all been practised in Guyanese society as a means of social control. The post-emancipation village movement, the kind of communal existence and kinship that pervade in rural village life, where there is some sense of an extended family and the whole village accepts responsibility for the discipline, guidance and training of all its members are within the African ethos.

Therefore proverbs, folk songs, nansi tori and others are performed for entertainment, but they always have a strong element of social control. They are used to give advice, to issue warnings, to urge errant individuals to change their wayward ways or face consequences. Sometimes they simply document and comment on human behaviour and the kind of practices that are disapproved of by the community. Those being entertained are also supposed to learn from them.

Related to this is the element of sexuality that is not taboo in traditional African culture as it might be in western. Many African rituals and speech acts express sexuality in order to exercise control. Both nansi tori and kwe kwe use sexuality in performance in order to address deviant sexual behaviour, promiscuity and breaches of expectations of chastity among members of the society. They warn that they are unacceptable. Ironically, both of these forms are disregarded and called ‘vulgar’ by many precisely because of this element of sexuality. It is not sufficiently understood how sexuality functions in the traditions.

There are also strong elements of rivalry, and many of these come together in the kwe kwe which is an excellent example of the African presence. It is not a tradition that is known to have been brought from Africa; it is Guyanese, having evolved in this country with major elements of the African world view and cultural traditions.

As a marriage ritual it is a rite of passage; it proclaims the chastity of the bride and both promotes and celebrates chaste behaviour in all women; it uses sexuality to exert moral control; it uses a theatrical performance form to entertain as well as perform wedding rituals; it expresses kinship and the joining of ‘nations’ (communities, families); it revels in rivalry between the same communities/families in a ‘play’ contest, and teaches good values.

Other factors of powerful Africanisms in Guyanese society have survived from religious practice. Because Christianity was imposed upon the enslaved, by the time of Emancipation many were Christian. Several of these ‘Christians’ maintained dual worship, since they would also engage in traditional spiritual religious practice. But a kind of church evolved which merged Christianity with several African traditions to produce churches known as revivalist or spiritualist because of the ritualistic and spiritual elements derived from African culture that they brought into Christian worship. These include elements of dance, drums, hand-clapping and in severe instances, possession and sacrifice.

These have their roots in the African belief in ancestor worship where the gods and the spirits of ancestors are invited to intervene in the lives of the worshippers for their healing, salvation, spiritual cleansing and good fortune, which sometimes includes material well-being. One of the purest forms of this survival is the Kumfa (cumfa) in Guyana where spirit possession by devotees is germane to the achievement of goals. There are other minor practices in which spirits of the water, air or earth are appealed to.

Some of these factors cause many skeptics to confuse these traditions with obeah, but they are different. The same lack of real knowledge caused obeah to be despised or ridiculed and fear of it, as well as the mistaken idea that it was demonic witchcraft, caused the colonial authorities to criminalise it.

True obeah which, as historians have documented, had real meaning and uses to the enslaved, was driven underground and it is not known whether any proper practitioners exist today.

Many of these aspects of African culture in Guyana have been misunderstood and there is often insufficient knowledge of them among the population. This ignorance has caused self-contempt, ridicule, fear and disappearance. But they are all parts of the African presence in the culture of Guyana which remains strong in most areas of social existence.