By Melanie Newton

“… yet, sadly, accidental rudeness occurs alarmingly often…

Best to say nothing at all, my dear man.”

(Albus Dumbledore, Harry Potter and the Half Blood Prince)

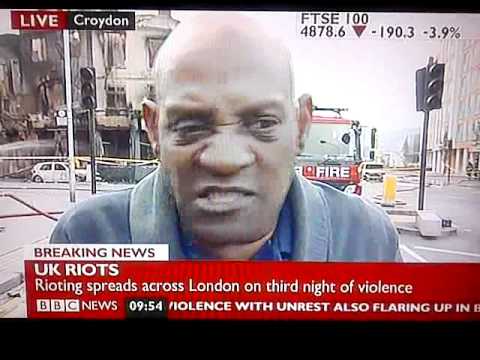

We may never know the name of the person who recorded and uploaded an August 9 BBC television news segment, in which anchorwoman Fiona Armstrong interviewed the Trinidadian born journalist and black British community spokesperson Darcus Howe. Thanks to this anonymous person’s quick thinking, the full shame of Armstrong and the BBC is now available on Youtube for all the world to see.

We may never know the name of the person who recorded and uploaded an August 9 BBC television news segment, in which anchorwoman Fiona Armstrong interviewed the Trinidadian born journalist and black British community spokesperson Darcus Howe. Thanks to this anonymous person’s quick thinking, the full shame of Armstrong and the BBC is now available on Youtube for all the world to see.

Armstrong interviewed Howe – who has worked as a BBC journalist – at the height of the recent disturbances that swept the UK. Things went downhill immediately, when Armstrong introduced him as ‘Marcus Dowe.’ After that, more or less every word Armstrong uttered was offensive. When Howe said he was not “shocked” by the riots given what was happening to “young people in this country”, she asked if he “condoned” the riots. She interrupted him when he said that the police “blew [Mark Duggan’s] head off”, patronizingly stating that: “we don’t know what happened to Mr. Duggan.” Armstrong’s vehemence was remarkable, given that the police admit they shot Duggan – what is in question are the circumstances of the shooting.

When Howe said his grandson could not count how many times the police had stopped and searched him, Armstrong lectured him like he was a naughty child, saying this was “no excuse to go out rioting.” A more reflective journalist might have asked Howe to comment on connections between the peaceful vigil outside Tottenham police station, allegations that police assaulted one of the women present, and the violence that followed. I suppose I shouldn’t really be surprised, given the neutral way in which the BBC has reported on Duggan’s arrest during a police crackdown on “black gun crime”, as though such a concept were even legitimate.

Howe then called events in Britain “an insurrection of the people” and drew parallels with Syria. Rather than ask a follow up question, she accused Howe of “being no stranger to riots” and being involved in them himself in the past. Later that day, in an email to the editors of one amateur online media watchdog, Armstrong defended her statement, saying she had been briefed that: “Mr Howe has in the past organised several demonstrations, some of which got out of control, and had once assaulted a policeman.” By Armstrong’s capacious definition, anyone who organises a public protest that goes awry is, apparently, a ‘rioter’.

Armstrong’s “no stranger to riots” comment looks even worse when stacked up against the facts of Howe’s life. It does appear to be true that Howe was once convicted of assaulting an officer who was trying to search him. However, in the Wikipedia age, there is no excuse for a BBC journalist not knowing that Howe was in fact acquitted of the charge of riot in the famous “Mangrove Nine” case of 1971. The judge in that case noted that: “there was ‘evidence of racial hatred on both sides’ – the first acknowledgement from a British judge that there was racial hatred in the Metropolitan Police Service.” By the end of the interview, I was impressed with Howe’s restraint. Armstrong should consider herself lucky that all Howe told her was that she sounded “idiotic” and ought to “have some respect for an old West Indian Negro.”

Within 24 hours, more than 1 million people had watched the video. On August 10, the BBC issued a carefully worded apology, admitting that some of Armstrong’s questions might have been “poorly phrased” and apologizing if anyone found the interview offensive. Even in the apology, however, the BBC sought to defend itself, observing that there were “technical issues” during the interview and neither Howe nor Armstrong could hear clearly what the other was saying. This may well be true but “technical” problems cannot explain Armstrong’s unprofessional line of questioning.

The rapidity with which the video went viral reflects a popular sense that the Armstrong-Howe exchange is somehow a microcosm of the social and economic crises facing Britain. Every media outlet seems to have an analysis of what the disturbances mean for Britain’s future. I feel neither competent nor called upon to offer an explanation. I am a historian, and my thoughts turn to the past as I observe how quickly the government has used this opportunity to adopt as right wing and punitive an agenda at it can without actually going so far as to advocate the abolition of democracy in Britain.

David Cameron doesn’t want to let “phoney human rights concerns” about publishing people’s pictures on the internet get in the way of restoring order. At the same time, he is considering legislation that would limit press freedom in the interest of getting information necessary to secure criminal convictions. In an example of public opinion-driven role-reversal, Labour Party leader Ed Milliband is warning the Conservatives not to go ahead with proposed budget cuts to the police force.

If the British government really wants to take this opportunity to roll back civil liberties, then British domestic and imperial history provides many fine examples of effective draconian measures. In his proposal to limit freedom of access to social networking sites, Cameron seems to be channeling William Pitt the Younger, British Prime Minister at the time of the French and Haitian Revolutions. Pitt cracked down on “correspondence societies” in order to stop radical popular organizing in Britain. But why stop there, why not go further back? If the jails are full, then reintroduce indentured servitude abroad as a punishment for crime. That certainly worked a treat during the English Civil War, and would greatly reduce youth unemployment in Britain.

Fiona Armstrong herself might be able to offer the government an instructive lesson in how to focus on lawlessness and irresponsibility and thereby avoid addressing a genuine need for democratization and social reform. Buried in Armstrong’s exchange with Darcus Howe is a more secret story of the British state’s relationship with poverty, racism, consumerism and social alienation. Armstrong, also known as Lady MacGregor, is the wife of Sir Malcolm MacGregor, 7th baronet and 24th Chief of the Clan Gregor. The ancestor of Armstrong’s husband, Sir Evan MacGregor, was Clan Chief and Governor of Barbados, Trinidad and the rest of the British Windward Islands at the time of emancipation in August 1838. One hundred and fifty years ago and on different soil, the ancestors of the MacGregors and the Howes would have viewed each other across an equally great social chasm.

By all accounts Sir Evan was a crafty closet racist. He dismissed black West Indians’ demands that emancipation should mean the end of racist inequity by saying that racial discrimination had been abolished with emancipation. He pointed out that British common law did not recognize distinctions based on race, so black West Indians were just stirring up trouble by making allegations of racism against the police force, the judiciary and the colonial government. MacGregor was fond of telling black civil rights agitators that discrimination against them had nothing to do with colour, but class, a form of exclusion that was perfectly legal in the 1830s. If black West Indians, by and large, lacked the property and education necessary to gain them access to political power, then that was the fault of an unfortunate past. Slavery was no longer the responsibility of either MacGregor or the British government, which had so generously made everyone equal.

MacGregor was not himself a slave owner, but he would not have been made governor if he had disagreed with the British government’s decision to pay £20m in compensation to slave owners for the loss of their human property (no compensation was paid to slaves). Planters owed so much money to British merchants and financial institutions that the money just had to be paid, or emancipation could have spelled financial disaster. Still, in our own current age of the great state-funded corporate rescue package, I’m sure we can understand the need for such a stabilizing measure. MacGregor placed unprecedented numbers of men of colour in colonial civil service positions. All of them, to the last man, were appointees who had made it clear they would stop harping on about equality once they got a high profile position and a civil service salary – but that was hardly MacGregor’s fault.

Sir Evan was a military man who came to the West Indies as a turbulent time. He met the efforts of ex-slaves to carve out independent lives with the full punitive capacities of the state– it was during his tenure that most of the modern police forces of the southeastern English Caribbean were organised. These new police forces initially existed for no other real purpose than to keep former slaves at work on the estates, or put them in jail if they had any ludicrous notions of personal independence. MacGregor and his generation of West Indian colonial governors were sent out to ensure that former slaves, as far as possible, became legally free subjects who were dependent on estate wages for their survival. Imperial officials spoke frequently of their concern about black ‘laziness’ – a metaphor for the fear that black West Indians would rather work for themselves than for low wages on a sugar estate.

To combat this, ex-slaves had to learn to want things that they did not need – they must be encouraged to equate civilization with owning what could only be bought from Britain, and paid for with wages earned from estate labour. Had cell phones and Burberry suits existed in 1838, any ex-slave who did not want them might have run the risk of being seen as “regressing into savagery” and resisting the “civilizing force” of consumption and the market. And yet, ex-slaves who showed a disposition to dress up in “finery” were punished for reaching “above their station”.

MacGregor died in Barbados in 1841, just three years after the arrival of legal freedom in Trinidad and elsewhere. By then, it was already clear that most of the radical democratic possibilities of slave emancipation would go unrealized. This was thanks, in no small part, to the efforts of men like MacGregor, British men dedicated to making sure slave emancipation, one of the most important civil rights measures in modern human history, should not overturn the social, economic or political order. So, if Fiona Armstrong insulted Darcus Howe, she really can’t be blamed, since history was really only re-enacting itself in some small way through her.

By this point, I imagine some readers are quite outraged: educated Britons tend to get upset when anyone negatively invokes Britain’s imperial past as a lens for thinking about its current social issues. These days, some British historians are fond of talking nostalgically about empire as a time when the world was a much saner and safer place. The BBC often interviews such people, lending legitimacy to their views. I fear that it would be a waste of time that BBC journalists should respond to this crisis by learning something about colonial history. At the very least, the moment calls for some reflection on the Harry Potter quote at the beginning of this piece, if the BBC cares to understand why their apology rings hollow.

Yet Armstrong’s rudeness is no more accidental than the rapidity with which voices have come to the fore attributing the recent criminality to the ‘blackening’ of British culture. These are echoes of those who, not long after emancipation, viewed abolition as a failure because of widespread social unrest across the West Indies. The Armstrong Howe exchange and the current crisis in Britain have at least something to do with Britain’s failure to acknowledge how profoundly racism and empire have poisoned the country’s public life. Racist language, couched as state militarism and punishment, remains a constant reservoir of possibility, always available when British elites do not want to have a real discussion about their social problems. Few British elites, in our own age or in any other, want to admit that, historically, states do tend to get the forms of criminality that they deserve.

To see the Howe-Armstrong interview, go to: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=biJgILxGK0o