We are in the midst of one of those now familiar seasons, when, for brief periods, serious allegations of inappropriate behaviour by public officials surface, set tongues wagging and, in the face of the indifference of the political administration, wither and eventually die.

President Bharrat Jagdeo himself has been cited for what was felt to be an unwise, even inappropriate friendship with a US-based Guyanese businessman Edul Ahmad who, just last week, had an indictment returned against him by a federal grand jury on charges of participating in a multi-million dollar mortgage fraud scheme.

In this instance, the President has publicly admitted to his friendship with the businessman though, up until a few days ago, the government had maintained a stony silence on a shipment of cargo sent to him by Ahmad and said to include kitchen sinks and roof tiles. It transpires, according to an official statement, that the President bought the consignment for his personal use, a revelation that leaves one to wonder about the protracted delay in making this disclosure.

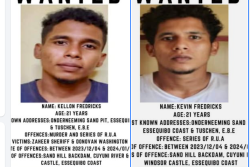

The most recent and least surprising of the recent allegations has to do with the Guyana Police Force, more specifically, with allegedly corrupt senior officers and junior ranks said to be up to their gills in the drug trade, serving both as ‘minders’ for separate drug operations and as beneficiaries from a criminal empire which the Force repeatedly says it is committed to fighting.

The actions of some police officers appear to give credence to at least some of the revelations.

The best-known allegation of improper behaviour by a high official of the PPP/C administration occurred some years ago and had to do with a claim that former Minister of Home Affairs, Mr Ronald Gajraj had promoted, directed or otherwise engaged in activities which involved dispensing summary justice to persons believed to be associated with the ‘crime wave.’ On this occasion and under intense public pressure triggered by the trail of death left by the killers, a Commission of Inquiry was set up. At the conclusion of its deliberations Mr Gajraj was cleared, although it found that his “close association” for undercover purposes with ex-policeman Axel Williams, who was associated with a death squad, was “unhealthy.” He lost his ministerial position, but was still promptly dispatched to India as Guyana’s High Commissioner.

In the various other instances in which public inquiries have been called for and appeared to have been warranted, the government has simply brushed the calls aside. President Jagdeo himself has asserted that accusations of inappropriate behaviour by high officials must be attended by hard evidence if a case is to be made, though that pronouncement is widely regarded as contrived and evasive, its critics contending that it has less to do with issues of evidence and more to do with the disposition of the administration to having its high officials being held to account over accusations of wrongdoing.

In our editorial of Tuesday, July 19 (‘Lessons in democratic behaviour‘) this newspaper commented on the dismissal of the former Trinidad and Tobago Cabinet Minister Dr Mary King by the Persad-Bissessar administration after she was accused of using her ministerial influence to help secure a government contract for a firm in which she had a family interest. Here was a case in which a cabinet minister in a sister Caricom country had been fired following an investigation into charges of improper conduct. We made the point then that had Dr King been a minister in the administration here in Guyana, an accusation of that nature would probably not have gotten beyond being reported in the media.

We believe that the case of Dr King provides evidence of a culture of accountability of high officials in Trinidad and Tobago that is absent from the governance culture here in Guyana.

Elsewhere in the Caribbean there is more evidence of that culture of accountability, one that requires high officials to subject themselves to public scrutiny when serious charges of wrongdoing are levelled against them.

There is the instance earlier this year in which Prime Minister Bruce Golding of Jamaica was required to face the Manatt-Coke Commission of Inquiry over allegations of official attempts to block the extradition to the United States of Christopher ‘Dudus’ Coke, a well-known Jamaican drug lord. What was remarkable about Mr Golding’s testimony before the Commission of Inquiry was the fact that the Prime Minister of a Caricom country was subjected to what would have been, to say the least, the discomfitting experience of having to publicly admit that he had known a drug lord, a “Don” in Prime Minister Golding’s own words, who, again in Mr Golding’s words, “exerted considerable influence within the community of Tivoli Gardens.” It is apposite to note that there are similarities between the ‘Dudus’ Coke case in Jamaica and the Roger Khan case here in Guyana, though calls for a public inquiry into allegations that Khan was well-connected with the Jagdeo administration were brushed aside by the government.

Mr Golding is still Prime Minister of Jamaica. The experience of him being subjected to public scrutiny, however, would have provided the citizens of his country with assurances that they live in a society in which high officials, including the Prime Minister, are by no means above reproof.

The second case concerns the Prime Minister of Dominica, Mr Rooseveldt Skerrit who, an investigation has determined, must face his country’s Integrity Commission following an accusation that he exerted his official influence to facilitate the granting of state concessions for a business venture in which he is said to have an ownership interest.

Interestingly, the investigation raises the issue as to whether Mr Skerrit’s earnings as Prime Minister place him in a position to afford such a business venture, and it has been determined that Prime Minister Skerrit must answer to his country’s Integrity Commission notwithstanding the fact that he has openly denied the alleged business interest.

Here again is a case of the existence in the Caribbean of a political culture that renders high officials accountable. In this instance it is apposite to note that here in Guyana publicly expressed concerns over what is believed to be unaffordable acquisitions by officials of state do not appear to trouble Mr Jagdeo’s administration.

We cite these cases if only to restate what we believe to be a legitimate national concern over compelling evidence that the Government of Guyana appears to embrace an approach to the matter of the accountability of its high officials that departs radically from that which obtains elsewhere in the Caribbean. Indeed, it seems, sometimes, as though we are unmindful of the importance of being guided by the best available governance practices, failing to recognize that apart from inflicting on our country the stain and the indignity of being perceived as an aberration in a region that holds itself to higher standards of accountability by high officials of state, we create the conditions for incrementally worse excesses of lawlessness that question such claims as we make to being a society in which power and influence do not protect against penalty for indiscretion.