By Marjorie Chester

Is the increasing popularity of imported ready-made women’s clothing threatening the survival of Guyana’s dressmaking industry? The answer, it appears, depends on whom you ask. Among some fashion-conscious Guyanese women, particularly those who consider themselves mature ‘divas’ there appears, more often than not, to be a preference for the uniqueness the skilled seamstress offers. Even they admit, however, that the era of scores of local dressmakers whose bedrooms and living rooms appeared permanently overwhelmed by piles of fabric, half-done jobs and finished clothing is a thing of the past. “The dressmaking industry may not be dead but it no longer flourishes in the manner that it did 30 years ago,” says Norma Maynard, a mid-forties schoolteacher who has maintained a relationship with a seamstress throughout her adult life.

There is no mistaking the phenomenal growth in the local clothing retail industry. Cheaper, ready-made women’s clothing abounds, a spin-off of the ‘explosion’ of clothing factories particularly in parts of Asia, the United States and Latin America, notably Mexico and Brazil. The advent of internet shopping too has provided merchants with a huge advantage and retailers now find it easier to develop permanent ‘buy in bulk’ arrangements either with importers or with local wholesalers.

There are women, like Norma, who still do not trust their figures to the vagaries of the off-the-rack blouse, dress or trouser suit, preferring to rely on their long-standing relationships with their seamstresses, but the issue of affordability is important. On the whole Norma estimates that made-to-order clothing can cost as much as three times more than ready-made attire. ”You can hardly blame the thousands of Guyanese women whose wages are small and whose obligations are many. A cheap working blouse can still be acquired at around $1,000. You cannot go anywhere near a dressmaker with that kind of money,” she says.

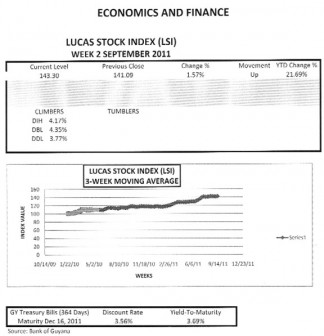

LUCAS STOCK INDEX

The LSI gained close to one and a half points on the trade of four stocks. Banks DIH (DIH), Demerara Bank Limited (DBL) and Demerara Distillers Limited (DDL) all traded up gaining 4.17, 4.35 and 3.77 percent respectively. The price of Republic Bank’s stock remained stable. Despite the gains, the spread between the index and the risk-free Treasuries due to mature in December 2011 remained below 20 percentage points.

Norma is by no means singular in her assessment of the transformation that has taken place. Most of the women with whom you speak believe that times have changed, and that the dressmaking industry out of which so many Guyanese working-class women once made a “decent living” is under threat from the mountains of imported clothing now available in Guyana.

Prices apart, having made-to-order clothing is a process and when the extent of the demand created by the increasing number of women who both work and entertain themselves is taken account of, the verdict, in the vast majority of cases is that the off-the-rack option removes the hassle. Not that Guyanese women have become less fashion-conscious. They appear, however, at least in many cases, to have settled for what, quite often, is the less than perfect fit that goes with buying ready-made clothing.

Vaulda Welcome is a popular seamstress who plies her trade from V’s Fashions, her own shop in the Bourda Mall looking out onto Church Street. The trade, she says, has indeed suffered a decline; there is no denying the shift to the off-the-rack option. She has, however, managed to retain the loyalty of some of her longstanding customers, women like Norma whom, she says, “care about how they look.” For them, visiting the seamstress has become a habit. These customers, she says, are preoccupied with uniqueness; they favour one-of-a-kind pieces, and a seamstress who is familiar with their favourite colours and style and, perhaps above everything else, who “fits them well.”

These days, Vaulda says, she still manages to secure orders from working women for uniforms though even that niche has long been encroached upon by the practice of importing some uniforms.

Survival for those seamstresses who have traditionally prided themselves on being specialists in turning out female attire has meant having to change their game. Vaulda says that she too has had to respond to the forces of the market. School uniforms, for both boys and girls, have become an important money-earner though cheaper mass-produced school uniforms – shirts, kimonos, skirts and trousers – are also flooding the market. The arbitrariness in determining sizes and what are often the ill-fitting outcomes no longer seem to bother parents that much, a circumstance that appears to account for the growing popularity of the clothing factory that simply stitches to pre-determined patterns and sizes. To survive in the school uniform business Vaulda has had to find ways of competing with the downtown stores and arcades, cutting her profits in the process.

There are, too, the seasonal windfalls; the holiday periods like Christmas, Mash, Emancipation and, of course, June the month of brides. For Vaulda, however, the business cannot any longer be solely about clothing. She is already preparing samples of window curtains, cushions and slip covers which she will shortly be placing on display outside her shop. Diversification has become the only means of survival. Her prices, she says, will be competitive though she admits that the volume of orders has slipped in the face of competition from the high street retailers. The richly embroidered curtains imported mainly from China are tough to beat. Next year, she hopes to produce samples and exhibit them from as early as September in order to try to bring more orders in.

Alterations, Vaulda says, has become a lucrative part of the dressmaking industry. It is, among other things, a kind of last laugh for seamstresses, a concession on the part of consumers that cheaper, off-the-rack clothing often costs more than what you pay in the store. Sometimes, depending on the cost of the dress and the nature of the alterations, the eventual cost can be much higher. “Cutting, hemming, adjusting sleeves, inserting darts” and generally fitting ready-made clothing, mostly imported bridal gowns could cost between $3,000 and $8,000, depending on the extent of the alterations. Imported bridal gowns have become commonplace and since women want to look their best on their wedding days they find it hard to live with the off-the-rack imperfections.

Weddings can bring welcome windfalls. Vaulda sometimes outfits entire wedding parties, producing the bridal gown, bridesmaids’ dresses, groomsmen’s shirts and flower girls’ dresses. A single bridal gown could fetch $50,000, a welcome payday though still less expensive than what it costs at the local bridal stores.

Vaulda is training young women in the craft of dressmaking through a programme being run by the Ministry of Labour’s Manpower Development. It is she says, a way of earning more while contributing to job-creation.

Quality counts

As far as Mona Sukhai is concerned “quality counts.” She too acknowledges the pressures that have been placed on the dressmaking industry by ready-made imports though she insists that Guyanese women are no less passionate about well-tailored clothing. She has, she says, placed her reputation on the line and it has paid off. The approach to turning out high-quality jobs has kept her customers loyal. She too, however, has been compelled to pay more attention to school clothing. This year, she says, her establishment was as swamped with orders for school uniforms as it has ever been. At one point she had stopped taking orders. She talks about rising prices for fabric like gabardine, cotton and polyester, the vast majority of the material used in the production of school uniforms. Nor is she impressed with the handiwork of the factories that produce the off-the-rack school clothing.

What Mona has done too is to invest in the training of her employees. By training women in design and cutting techniques she ensures that standards are kept high. There is, she believes, little room for error in an industry that faces strong and continually growing competition.

Businesswoman that she is Mona understands the rationale behind the preference for cheaper Asian and North American ready-made clothing. Simply put, it’s the hassle of having to purchase fabric, buttons, edging and other accessories, taking these to the dressmaker, having measurements and fittings done then waiting for the clothing to be completed. At the end of all that you still pay more for the product. She believes though that the end product is worth the wait. Not everyone agrees with her.

She makes no secret of the fact that made-to-order dresses are usually more expensive. “Materials are expensive, Some fabrics like organza and chiffon for social wear could cost as much as $3,000 per yard. Prices for all types of linen, tetrex and suiting material have been climbing as well but the orders for office wear have not fallen back significantly,” she says. The cost of sewing a dress, skirt or pant suit could range from $3,000 to $5,000, depending on the intricacy of the design. She points out, however, that these prices have not changed “in years.”

Alterations are only a small part of Mona’s business. Apparently, her customers prefer to bring her patterns or actual pieces of imported clothing to be reproduced. She believes that a serious downside of purchasing ready-made women’s clothing, even brand-name clothing lies in the quality of the fabric. “Very often the pieces lose their shape, they shrink and the fabric warps after washing. Water and soap are not good for certain fabrics,” Mona said. The reproductions help keep her in business.

Lady ‘B’s mobile boutique

Barbara has found it more profitable to buy and sell imported clothing. Seven years ago she shifted her focus from tie dying and selling sewn outfits to buying and selling ready-made dresses among other things. Time and circumstances have constantly changed her operation. At first it was the wholesale stores, then the barrel trade. She still purchases imported clothing in bulk. That is where the money is. People have become less discriminating and even that which is designated ‘seconds’ in North America is sold as perfect clothing here. Out of style and out of season women’s clothing are sometimes good sellers too; as is the practice of buying women’s clothing literally “in bulk.” The prices per barrel after clearing local customs fluctuate between $50,000 and $100,000 depending on the contents of the barrel. The barrels keep coming and the business continues to do well.

Over time in the face of a reduction in customer visits to her boutique ‘Lady B’ decided that she must go to her customers. She takes her clothing to their homes, selling at significantly reduced prices and undertaking after-sales services like alterations. The barrel/suitcase trade in ready-made clothing also allows some flexibility in pricing. A cocktail dress from the barrel trade could go for $6,000 – $8,000, cheaper than the $15,000 – $25,000 price tag on a similar item purchased from a boutique in Georgetown.

The local dressmaker appears to have come to terms with the fact that the nature of the industry has changed, that cheaper imports have disfigured the profession and that the aggression of the global clothing manufacturing sector may well mean that things have changed forever. Some, like Elsie Stanton whose D’Urban Street establishment was never short of customers, particularly during the 1970s, have slipped quietly into retirement, “coming out” again for special jobs, favours to friends and relatives.

Others have sought full-time work in other fields while others still soldier on, seemingly determined that the Guyanese fashion culture will not immerse itself entirely into what is now a multi-billion dollar and increasingly appealing industry of ready-made women’s clothing.