By Alim Hosein

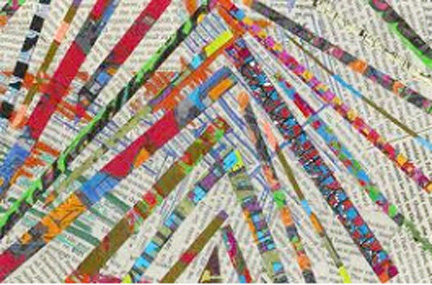

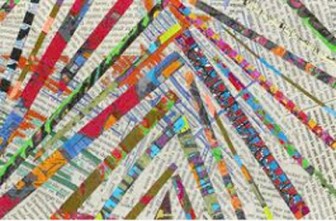

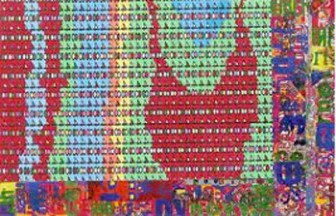

As part of the Guyana Prize for Literature 2010 awards activities at the beginning of this month, items from a series of prints done by one of the judges, Stewart Brown, were exhibited at Castellani House. The small prints were taken from a series entitled Babel that Brown had exhibited in 2006, 2007, 2009 and 2010 in various places including Barbados, Jamaica, the United Kingdom and Africa. Given the title of the series, the prints formed an interesting complement to the Guyana Prize week of activities.

The word ‘Babel‘ suggests confusion of sound, a situation in which language, the primary means of human communication, becomes so diverse and multiplex that communication is thwarted rather than enhanced, and dissonance rather than solidarity results. The original concept of Babel comes from the Bible, but the age in which we live – the age in which technology is being used not only to allow each person to access a multiplicity of channels of communication, but also to become the creator of his or her own flows of information – gives a whole new resonance to the concept.

Brown reflects this relentless torrent of information – the “printed textual detritus that inundates our lives, much of it uninvited” as he puts it – in the series. Using elements of language – words, numbers, printed pages and fragments – he images a breakdown of communication. Babel suggests a distance between the streams of information and the human recipient. Information takes on a life of its own – one can imagine tens of trillions of bits and bytes of information streaming around the globe and filling up ‘empty‘ space, but with the human person not actually connected with much of that flow. Babel is therefore an ironic comment, that the age of communication also overwhelms connection.

Brown reflects this relentless torrent of information – the “printed textual detritus that inundates our lives, much of it uninvited” as he puts it – in the series. Using elements of language – words, numbers, printed pages and fragments – he images a breakdown of communication. Babel suggests a distance between the streams of information and the human recipient. Information takes on a life of its own – one can imagine tens of trillions of bits and bytes of information streaming around the globe and filling up ‘empty‘ space, but with the human person not actually connected with much of that flow. Babel is therefore an ironic comment, that the age of communication also overwhelms connection.

But the series also reflects Brown’s fascination with the graphic forms used to externalise language. The pieces, which are small – the size of a novel – are densely crowded with letters and words. Different pieces give different takes on the graphics of

But the series also reflects Brown’s fascination with the graphic forms used to externalise language. The pieces, which are small – the size of a novel – are densely crowded with letters and words. Different pieces give different takes on the graphics of  language – in some cases Brown plays around with individual letters, repeating them, magnifying them, arranging them against the backdrop of crowds of other letters. In other pieces, the letters are crowded and marshalled into ranks and files. In others, they form patterns which look like aerial views of cities. In a few pieces, the shapes of the letters break down and only the colour leaking through the spaces between them gives some hint of the form. In all the pieces, barely-recognised words, letters, numbers emerge and merge, creating new messages out of the breakdown of many messages.

language – in some cases Brown plays around with individual letters, repeating them, magnifying them, arranging them against the backdrop of crowds of other letters. In other pieces, the letters are crowded and marshalled into ranks and files. In others, they form patterns which look like aerial views of cities. In a few pieces, the shapes of the letters break down and only the colour leaking through the spaces between them gives some hint of the form. In all the pieces, barely-recognised words, letters, numbers emerge and merge, creating new messages out of the breakdown of many messages.

A third aspect of the work lies in the production of messages. Brown says that “Babel is an ongoing series of collages, paintings, digital prints, artist’s cards, boxes and installations.” The pieces on show at Castellani are prints of those paintings, collages and prints that Brown had done, but he notes that they are not to be seen as copies of the original work. Instead, he says, “…the several processes of scanning, editing, cropping, colouring and printing change those images in ways that are particularly significant in the context of this Babel project, remaking them as printed text-derived artworks in their own right.” Technology is therefore an implicit part of the process of creating the artwork, in the same way that brushes and brushstrokes are integral but usually unheralded elements in the success of a painting. Also, in the same way that the technologies of writing, then printing, then digitising have amplified language to the point where it overwhelms its function (information overload), the means of technology are being used to create new ways of seeing, interfacing, understanding (calligraphic beauty created not only by hand but by technology).

Babel exists between such poles. It focuses the technologies of communication – the means of giving form to the sounds of language, of externalising, recording, reproducing, conveying language. But it also reflects the human involvement in language, including the changes that language itself goes through as different persons and communities appropriate it to create their own meanings. In this last sense, Babel has a positive resonance, as the criss-cross of communication re-energises and fertilises language.

At the same time, there is a fascination with the world in which one is swamped by language. As Brown says in his notes to the exhibition, “Babel is essentially a playful, whimsical, ironic response to the various pleasures and pressures of a life devoted, one way or another, to the text.”

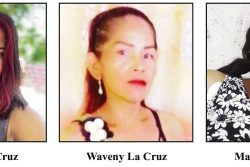

Stewart Brown was Chairman of the Jury for the first Guyana Prize for Literature Caribbean Award. He is Reader in Caribbean Literature at the Centre of West Africa Studies, University of Birmingham. He has been closely following Caribbean and African writing since the 1980s. He is also a prize-winning poet.

The Babel range of images can be seen on www.catalystpress.co.uk

The prints on show at Castellani will be donated to libraries in Guyana.