RIO DE JANEIRO (Reuters) – It is a project that should symbolize the transformational benefits of hosting the 2014 World Cup — a sleek new monorail train gliding above Brazil’s steamy Amazon city of Manaus.

But Athayde Ribeiro da Costa has a different take on it.

With just under 1,000 days before the first ball is kicked, the chief public prosecutor in Amazonas state sees the monorail as part of a trend of overspending and poor planning as Brazil rushes to make up for a slow start to its preparations.

“We are very worried about overspending,” he said. “We are in favour of the Cup — it can bring lots of opportunities for people and help resolve infrastructure bottlenecks, but this can’t be done at the expense of misuse of public funds or corruption.”

Concerns are mounting that Brazil’s push to speed up its preparations for the soccer tournament risks fueling corruption and an explosion in costs dwarfing other “mega-events.”

Last year’s World Cup cost South Africa about $4 billion but Brazil’s official estimate already stands at about $13 billion, including transport projects, stadium construction and airport expansions, making it certain to be the most expensive in history.

President Dilma Rousseff spoke in March of 33 billion reais ($18 billion) in World Cup investments and some private estimates are already way higher, putting the final bill at an eye-popping $60 billion in one case — bigger than neighbouring Uruguay’s annual economic output.

Legal cases are proliferating as prosecutors like Da Costa investigate suspected overspending and abuses of bidding processes. Da Costa heads a group of 12 prosecutors focusing on World Cup cases — one for each host city — and says there are more than 80 civil investigations under way throughout Brazil.

A Sao Paulo federal judge this month ordered work suspended on the expansion of Sao Paulo’s Guarulhos international airport, saying that bidding rules had been ignored under the excuse of urgency. Another judge overturned that decision.

The legal cases could help save Brazilian taxpayers a lot of money but also risk causing yet more delays to a schedule that is already pushing the limits of just-in-time readiness.

“If you make it more transparent you might slow it down, and therefore increase the costs,” said Christopher Gaffney, a visiting professor of urbanism at Rio’s Fluminense Federal University. “If you don’t make it more transparent, you’re guaranteed to increase the costs because everyone’s going to have their hand in the till.”

Spiraling costs are a familiar ritual of World Cups and Olympic Games. In this case, though, they are sharpened by some very Brazilian problems — endemic corruption, bureaucratic and legal hurdles and high construction costs driven by a lack of capacity in its robust economy.

Some projects, including another planned monorail in Sao Paulo, are not due to be ready until just weeks before the start of the tournament in June 2014. Delays have already drawn rebukes from world soccer body FIFA and ruled out two of Brazil’s 12 host-city stadiums being ready in time for the curtain-raising Confederations Cup in 2013.

Work has yet to begin on five of the 13 airports that need to be expanded for the month-long World Cup, this soccer-crazed nation’s first on home soil since 1950.

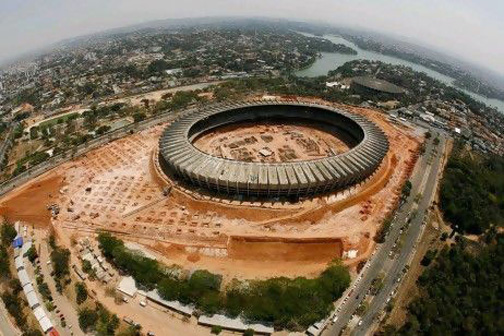

The government said this month it was confident that stadiums and airports would be ready on time, but that it was concerned over slow progress on “urban mobility” projects like the Manaus monorail. Seven of the host cities have yet to start any of their planned projects. The risks to the fragile timetable were rudely exposed this month when Rousseff visited Belo Horizonte to start the 1,000-day countdown only to be greeted by a strike by workers building the southeastern city’s stadium.

Rousseff’s government has injected some urgency into its World Cup plans, rushing through Congress in July a law that streamlines the bidding process for events related to the World Cup and the 2016 Olympic Games in Rio de Janeiro. That was a red flag for transparency groups and public prosecutors, who have slammed the change as opening the floodgates for over-spending and corruption — already a common problem in major construction projects in Brazil.“The risks of having projects without the correct procedures and transparency are rising exponentially,” said Caio Magri, a public policies adviser at the Ethos Institute, which works to promote corporate responsibility.

“The amount spent itself doesn’t matter — 50 billion reais ($28 billion) would be very small to make up for what is lacking in Brazil’s cities. It’s not the size that’s important, it’s the legacy.”

Prosecutor General Roberto Gurgel has asked the Supreme Court to declare the new bidding rules unconstitutional, saying they risk a large-scale repeat of the Pan-American Games in Rio in 2007, whose budget rose to 10 times the original estimate.

Back in 2009, the Brazilian Football Confederation estimated the 12 stadiums being refitted or built for the World Cup would cost about 2.2 billion reais — a figure that two years later seems quaint. The government now sees them costing more than triple that at 6.9 billion reais.