Lennox J Hernandez

Broken and spartan, the Anglican Church of St Barnabas, located at Regent Street & Orange Walk, Bourda, Georgetown, opened as a relatively small building in 1884 in a north-south orientation with the main altar at the northern end, and, after a series of grand additions and alterations, consecrated in 1938 with an east-west orientation and the main altar at the east end, is no more.

The demolition of St Barnabas Church seems to have been first considered in 1969, thirty-six years after the series of grand additions and alterations that made the plain, but “neat and pretty” original church more spectacular, but which at the same time, became the building’s sword of Damocles, that led to its eventual demise. By the time this is read, the building would have been completely demolished and much written and said on the historic value of the building, the difficulties of the Anglican Diocese in maintaining the church, the lack of vision of certain agencies, the concepts of consecration and deconsecration, and even on the sale itself. This article will celebrate the church by examining the history and physical development of the building that housed the church – this is a preliminary study, more research is to be done.

Bishop William Piercy Austin laid the corner stone of the St Barnabas Church on August 14, 1884; and he dedicated the completed building on October 20, 1884, at its opening. James Rodway, in The Story of Georgetown (1920) describes this original St Barnabas Church as a Mission Chapel, the Mission being first started in a circus tent – the Gospel Tent. A Daily Chronicle article of Friday, March 25, 1938, tells us more of the beginnings of St Barnabas. For example, that the Gospel Tent was pitched on the old Bourda Green which was the site of such religious services for a long time, and that the encouraging attendances resulted in a call for subscriptions to build a church in the area. Interestingly, the said article notes that there was an indifference to the call for subscriptions by the “better class” of the population. Eventually, St Barnabas Church was built through subscriptions from mostly residents around the Bourda area whom the article describes as the “peasant class” and noted that the lack of attention to the church by the “better class” continued even after the building was enlarged and aesthetically improved upon in the 1930s. This new church, completed around 1933(4) was oftentimes referred to as the “Bourda Cathedral,” but the great builder of the Church, Rev J T Roberts-Rea, preferred the name “Pauper Church.” Maybe this limitation on the finances of the church is responsible for its spartan interior when compared to other churches – no stained glass window over the altar, for example.

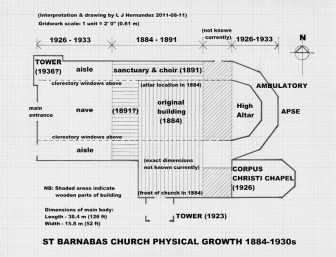

The original church building was described in the Daily Chronicle article as plain, though “… singularly neat and pretty with its neat face and palm trees.” A newspaper photograph (source not now known) shows a simple one-storey timber building with its gable end facing Regent Street, having two tall windows and a circular skylight, as well as an eastern extension with the main entrance to the church. Intriguingly, this original building was constructed in a north-south direction (the longest dimension placed along a north-to-south axis) with the altar at the north end of the building. This was contrary to the normal alignment of Christian churches at the time, the ritual demanding an east-west alignment and the altar at the east end of the building: it was not until the 1926-1934 alterations of the building that St Barnabas met this ritualistic requirement. Studying old photographs (from various Daily Chronicle articles of 1938) written descriptions (mainly The Daily Chronicle article of Friday, March 25, 1938) and the foundation layout seen during the demolition, a physical growth stages of the building was developed, but with some gaps. The original building (1884) may have been no more than 18.9 m (62 ft) long by 10.4 m (34 ft) wide, oriented north-south; whilst the main body (nave and two aisles) of the final building in 1934 reached about 38.4 m (126 ft) long by 15.8 m (52 ft) wide, oriented east-west.

The person credited with the spiritual and physical growth of St Barnabas is Canon James Thomas Roberts-Rea, who served as its priest from 1889 to 1943: he died on November 2, 1944. Within two years of his appointment, Rev Roberts-Rea began a passionate and life-long re-building of the church using his own finances, culminating in the St Barnabas we have come to know. As early as 1891, the building was extended along the north and possibly the west; the northern extension housing the chancel, including the choir stalls and sanctuary. In 1895, a spire, about 9.2 m (30 ft) from the roof of the building was built about midway over the nave of the church, of which one written account said “… it was a prominent landmark for many years.” The foregoing construction works continued the use of timber, but later works introduced reinforced concrete (1923-1930s) and repairs to the old northern timber wall introduced brick (post 1930s?). There must have been a number of changes to the building prior to its next major modification which began with the construction of the southern tower in 1923, but records of these are not currently available. This first tower, about 20.1 m (66 ft) high, topped with a pyramidal spire, and built entirely of reinforced concrete, was located directly off the southern (front) wall of the original building, facing Regent Street, as seen in the Daily Chronicle March 27, 1938 photo. The tower housed the belfry and a loft, and became the new main entrance of the church. During 1926, the Chapel of Corpus Christi was built, in concrete, forming a south-eastern extension to the building, and this had its altar in the east as required. (Then, between 1926 to 1933/4, a total physical transformation of the church was done with three major additions; firstly, the five-sided apse at the eastern end forming the new sanctuary (with High Altar) and an ambulatory (walking space) around the eastern wall of the sanctuary; secondly, the extension to the west of three bays which became the new main entrance; and, thirdly, a tower with a pyramidal spire, of about 30.5 m (100 ft) ax the north-western corner of the building, housing the new belfry.

To make way for this phase of re-building, the 1895 spire over the original north-south nave was removed and a higher roof constructed. These additions would have been planned so as to “turn” the church the ninety degrees required to have the altar at the east. There must also have been changes in the interior of the pre-1923 timber sections of the building to form the two lines of east-to-west internal columns that carried the clerestory windows above and divided the main body of the church into the classic arrangement of a nave (the central congregation area) with an aisle on either side.

These 1926 to 1934 additions were all in reinforced concrete, including floor and roof, and in our soft soil conditions a greater attention to the foundations would have been necessary; this may not have been done and so we have (had) a leaning tower and a moving away of the building’s body parts from each other.

Architecturally, the final design of 1934 is eclectic, mainly from the medieval architectural styles of Gothic and the earlier Romanesque that were being revived elsewhere at the time. Gothic is expressed, for example, by the buttresses off the clerestory (high-level) walls, and the turrets and the pointed decorations of the roofs and spires; whilst Romanesque is expressed mainly by the semicircular-head arch of the windows, doors, other openings, and spaces between the internal columns.

The use of the ancient Roman basilica form, the semi-circular apse, for example, is another Romanesque characteristic. Out of place, or maybe more “modern,” was the hip roof (not original in form and alignment) over part of the original building that linked it to the southern tower. A photograph in the March 26, 1938 issue of The Daily Chronicle shows the completed church with a different and more aesthetically-pleasing link, however: why and when was this change made?

Despite its difficult history, a microcosm of the social and economic circumstances of the area and people it served, the removal of St Barnabas Church from the Georgetown landscape is regrettable and will be a cultural loss to future generations.

(The writer acknowledges UG Architectural students David Bispat and Henry Noel for measuring the floor layout of the building at short notice, and Lyndon Hilliman and Mr Cush for allowing him access to the site during the demolition process.)