By Joycelyn Bacchus,

Joy Marcus, Halima Khan,

Susan Collymore & Andaiye

There’s a crisis in Guyana that almost everyone is ignoring – the crisis of mothers and other carers forced to work endless hours, often on no fixed schedules, and of the children they must leave to fend for themselves while they destroy their health labouring for a starvation wage.

Thousands of these women are domestic workers. Six of the 9 women in the Red Thread centre know their exploitation firsthand: we have performed paid domestic work in the homes of respectable middle-class women and men who overworked, underpaid and sometimes verbally abused us, who could afford to pay us a decent wage but believed that while their labour is of value, ours is not.

Here’s a summary of one true story:

One domestic worker’s story

M is employed by a couple on the East Coast Demerara to wash, iron, clean, mend and alter clothes for the whole household, and care two young children: bathe them, fix their meals, wash their clothes, comb the older one’s hair, help with her homework, read to the younger one and rock him to sleep and supervise both children. She is supposed to work Mondays to Saturdays, 9 am to 5 pm, but most days she is there till 6 pm when she returns home to care for her own child; she has an older child who doesn’t live with her but who she supports. She has no agreed lunch break; she gets one if she asks. If the employers have to go out in the evening they ask her the same day to stay till they return, which might be as late as midnight. They don’t offer her a taxi or a drop home so most times she sleeps over. For the past 6 months she has been told some Saturdays that she has to work on Sundays. Her young daughter is left alone when she can’t find someone to keep her at short notice. Her monthly wage is $36,000 (US$180) and basic expenses (food, rent, electricity, water, transport, school costs, phone) $52,445 (US$262) monthly. If she gets a day off it’s without pay. When the employers have houseguests her workload increases with no extra pay. She doesn’t get extra pay for working holidays either. No NIS is paid for her. M says, “These people hard bad.”

Domestic work is under-valued and under-paid because it is the same work that mothers perform unvalued and unpaid in their own homes; in other words, it is not real work and those who do it are not real workers. Domestic workers in Guyana are invisible in statistics and invisible to government, parties contesting elections, and even unions. They work in isolation, vulnerable to employers who “hard bad” because they have no protection either in law or usually in representative organisations that are recognized.

ILO Convention 189 says this

exploitation must stop

ILO Convention 189, passed on June 16, 2011, demands that domestic workers have the same rights as all workers. Although the Convention if implemented will not end their exploitation it will reduce it. Among other provisions the Convention says that domestic workers must:

● Receive a written contract of their employment terms and conditions (Art 7)

● Be entitled to minimum wage coverage where coverage exists (Art 11)

● Receive equal treatment with other workers in relation to: normal hours of work, overtime pay, daily and weekly periods of rest, and yearly paid leave (Art 10)

● Have conditions no less favourable than other workers, re social security protection, including maternity benefits (Art 14)

● Enjoy the promotion and protection of their human rights and fundamental rights at work including freedom of association and the right to collective bargaining (Art 3)

● Be protected against all forms of abuse, harassment and violence (Art 5)

● Have the right to a safe and healthy work environment (Art 13)

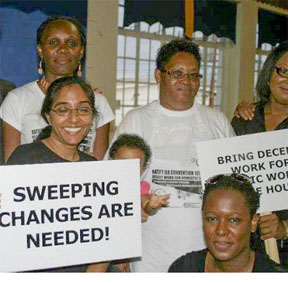

Organizing for the rights of

domestic workers

On October 7, World Day for Decent Work, domestic workers around the world launched a campaign to get Convention 189 ratified. In the Caribbean, Trinidad & Tobago’s National Union of Domestic Employees (NUDE) and the Jamaica Household Workers Association of Jamaica (JHWA) took the lead. At the Jamaica launch the Labour and Social Security Minister committed himself to getting the Convention ratified. In Trinidad & Tobago the Labour Minister, former head of the Oilfield Workers Trade Union, had earlier promised ratification but has not followed through.

Red Thread has joined the campaign. NUDE, JHWA, Red Thread and other groups are also forming a Caribbean Domestic Workers Network which will meet in mid-November to fine tune its agenda. Red Thread’s big priority is organizing with domestic workers in all of Caricom, including Haiti, and connecting with others in the wider Caribbean, South and Central America – among them Peru’s domestic workers’ union SINTTRAHO. That will make us stronger as we will make them stronger.

Another key priority is winning the rights of Caricom’s migrant domestic workers, whose largest contingents come from Guyana, Jamaica and Haiti. Since December 2009 they have had the right to work throughout Caricom once they are certified, but for many reasons, Guyanese domestic workers are still going to other Caricom countries as visitors and taking up jobs. They go in order to get the money to sustain their children although they have to leave them behind and often face inhuman treatment. In April this year, the Trinidad Express reported the Foreign Minister as saying that he had heard of Guyanese and “small islanders” being treated as “virtual slaves” in Trinidad & Tobago.

Most domestic workers in the world are migrants, from country to country or from countryside to city. They send massive amounts of money to families back home. Yet almost everywhere they are left alone to face terrible conditions.

Domestic workers elsewhere

are organizing and winning;

we must too

All over the world domestic workers are organizing and beginning to win. The passage of ILO Convention 189 was itself the result of domestic worker organising, including by NUDE and JHWA. In New York where most domestic workers are immigrants, many from the Caribbean, they have won a Domestic Worker Bill of Rights which came into effect on November 29, 2010, and California is likely to have its own Bill of Rights soon. In Peru, they won protective legislation in 2003 but it is not being implemented so they are now using the new ILO Convention (which they helped to win) to pressure their government to force employers to sign contracts.

In Guyana we will take the example of the late Clotil Walcott, grassroots mother and grandmother, an extraordinary organiser who knew what workers must do to win: draw out the connections between domestic workers in Trinidad & Tobago and grassroots women (and men) globally. She saw that women did the unwaged and low waged work of caring for the whole human race, doing backbreaking work in their homes, in other people’s homes, in factories and fields, to survive, and to feed, clothe and educate their children. Ms Walcott, who spent decades working in a chicken factory, founded NUDE and joined the International Wages for Housework Campaign (later Global Women’s Strike), which she co-ordinated in Trinidad & Tobago.

In Guyana, all of Caricom and across the Caribbean, that is what domestic workers must do to win – organize where they are and against the racial and other divides.