For the last two weeks a large group of mainly young people have been, quite literally, camping out in the precinct of London’s St Paul’s Cathedral. They are a part of the so-called anti-capitalist protests which have spread in an uncoordinated and haphazard way across a number of cities in the developed world.

By the oddest of coincidences I also witnessed in June similar protests in Madrid, came across by accident the equivalent near Wall Street in September and can attest to the great similarity in the composition and concerns of those at these separate events. What is striking is that despite the relative incoherence of the protesters demands, these young people are unlike their leftist predecessors in the late 1960s; they are socially distant from the unionised protests that followed the decline of older industries, and are utterly different in aspiration to those involved in much earlier demonstrations against nuclear weapons or the Vietnam War.

What mostly seems to set them apart from the past is that few of the protestors are ideologically driven. For the most part they do not espouse any philosophy or party politics but instead accept the role and power of the market, hope to be a part of the knowledge based economy that is meant to form their future, want to participate in a more socially aware consumer society, and aspire to living in a state in which there is fuller employment and a high degree of social justice. These mainly well educated, articulate and thoughtful young people feel that the market is rigged against them in favour of the wealthy and no longer has social utility.

What mostly seems to set them apart from the past is that few of the protestors are ideologically driven. For the most part they do not espouse any philosophy or party politics but instead accept the role and power of the market, hope to be a part of the knowledge based economy that is meant to form their future, want to participate in a more socially aware consumer society, and aspire to living in a state in which there is fuller employment and a high degree of social justice. These mainly well educated, articulate and thoughtful young people feel that the market is rigged against them in favour of the wealthy and no longer has social utility.

What is even more striking is that there are hundreds of thousands more – the ordinary citizens in work in both Europe and North America – who are not protesting, but who feel the same way. Opinion polls in the United States demonstrate how strong this sense of unease and discontent has become when they report that two thirds of Americans support the Wall Street demonstration. At base there is a sense that financial markets and politicians have parted ways with their ethical origins and there is deep resentment that the rewards being received by an ever smaller group of individuals are unjustifiable, dangerous and undemocratic.

Despite this, the solutions suggested so far are not as they might have been in the past, for the redistribution of wealth, but for a system that allows the possibility of all participating in a manner that is fair and more equitable.

In London this issue has come to a head in the most surprising manner. Originally its protesters wanted to set up camp outside the London Stock Exchange but because this proved impossible they ended up around St Paul‘s Cathedral which is nearby.

In a ham-fisted response, the Cathedral authorities first welcomed the protestors then locked its doors on the grounds of health and safety and subsequently seemed to suggest they were more concerned about the loss of tourist income for the Church than the message of those outside. The effect was to pitch the Church and its apparent loss of Christian ethics into a moral confrontation with the protesters and raised questions about its role among the wider population. The Cathedral authority’s stance gave the impression of placing the clerics on the side of the much disliked banking community and others whom the Christian message might more usefully be directed. ‘What would Jesus do?’ one protestor’s hand-made banner asked the Church.

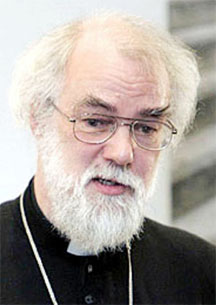

Finally, after resignations by leading churchmen and much searching of conscience, the Archbishop of Canterbury wrote an article for the Financial Times. What he suggested was thoughtful and measured, if poorly reported. He suggested four positive responses. He endorsed the position of the Vatican’s Pontifical Council which recently published a report on reforming the international financial system through regulation and incremental change. He called for the separation of routine banking from speculative transactions that risk the savings of individuals. He proposed that the recapitalisation of banks with public money should place obligations on them to reinvigorate the real economy. And he agreed with the Vatican that there should be a tax on financial transactions for reinvestment internationally and domestically also in the real economy.

If the demonstrators were the only manifestation of a growing concern the issue may fade quickly, but when the voices of some of the very wealthy such as Bill Gates, Warren Buffett or that of the German Finance Minister, Wolfgang Schäuble, are also to be heard expressing concern and similar solutions, then it is clear this is one that will not pass easily.

These are of course not just issues for the developed world. In the Caribbean, from Cuba to Barbados and beyond, young people and electorates want much more. It may be easy to attribute these problems to the seismic shift that is taking place in the world economic order, or ascribe them to globalisation and the homogenisation of politics, but this is to ignore that they require new thinking, new ideas and leadership if current manifestations of protest do not result in an absolute sense of disenfranchisement and alienation to the point of confrontation and conflict.

Many Caribbean people also feel that their politicians have parted ways with ethics and like their European and North American counterparts, they harbour a deep resentment that the rewards that are being received by an ever smaller group of individuals are unjustifiable, dangerous and undemocratic.

Many Caribbean political parties and politicians in the anglophone part of the region, whether from the centre right or centre left, still operate in the shadow of the post-Second World War thinking of the British Labour Party. This has a positive social value but less economic or political utility when it comes to addressing the practicalities of government, governance and implementation in nations that now have to depend on stimulating growth through encouraging private sector competitiveness.

The Caribbean has not experienced the intellectual and economic rebirth that has given confidence and growth to so much of Latin America. Instead it has failed to make regionalism work and seen this replaced by national and personal self interest and the absence of any significant growth. It is therefore unlikely to be immune from the sentiment for change that is arising in the cities and university campuses of Europe and North America.

Previous columns can be found at www.caribbean-council.org