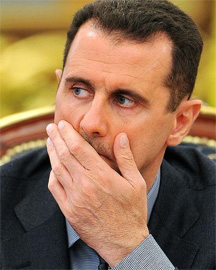

LONDON (Reuters) – Growing Syrian army defections do not yet pose a mortal threat to President Bashar al-Assad, but outside support could turn the dissidents into a national insurgency able to harass and exhaust his military.

As the country apparently slides further towards civil war, analysts say Assad will seek to deny nascent armed opposition groups sufficient territory to organise a guerrilla campaign.

His task will be the easier if the former soldiers are unable to obtain sustained expert help from abroad in organising their logistics and training recruits.

It is not yet clear if the defectors have forged such a network, either from the Syrian diaspora or foreign powers.

“If they get help from Turkey or certain Arab countries it could take maybe 5, 6 or 8 months to win against the regime,” British-based opposition activist Samer Afndi told Reuters.

“If no help will come, it will take a longer time,” said Afndi, a former Syrian state security official.

He said morale among many in the opposition was boosted by a raid by army defectors on an air force intelligence complex in Harasta near Damascus on Wednesday that had killed or wounded 20 policemen.

It was the first of its kind in an eight-month revolt against Assad’s rule by protesters inspired by uprisings which toppled the leaders of Tunisia, Egypt and Libya.

Turning point

But Afndi said the guerrillas, estimated by some analysts at several thousand, needed safe liberated areas in which to train and obtain logistical support.

“In truth, the armed insurgency is not strong enough to significantly threaten the regime at present,” Alan Fraser, Middle East analyst for risk consultancy AKE, told Reuters.

“However, with support from elsewhere, it may become more organised and capable of inflicting damage.”

“The turning point will come when it has the ability to control ground in the face of a regime counter-offensive.”

The exact strength of the dissident soldiers is not known and Syria’s ban on most foreign media makes it hard to verify events on the ground.

Colonel Riad al-As’aad of the Free Syrian Army told Reuters in Turkey last month that 10-15,000 soldiers, out of the roughly 200,000-strong military, had defected all over the country and that desertions were continuing every day.

Syria’s military is controlled by the president’s brother Maher and members of their minority Alawite sect, while the army is comprised mostly of Sunni Muslims, who also form the majority of Syria’s population.

Diplomatically Assad looks increasingly isolated, a factor that may eventually affect the military equation on the ground.

The Arab League agreed on Saturday to start talks with Syrian dissidents after a majority of its 22 members voted to suspend Syria’s membership of the pan-Arab body from Wednesday over its violent response to protests.

Regional powers may get sucked in

The rebellion has been met by a military crackdown that has killed more than 3,500 people, according to a UN count.

Syria blames the violence on foreign-backed armed groups who it says have killed more than 1,100 soldiers and police.

In a note to clients, London’s Exclusive Analysis consultancy said the attack in Harasta had likely dealt a psychological blow to the political elite around Assad.

“Further attacks of this kind would likely encourage further defections in the Syrian Army, sensing that it might be on a losing side.

“Along with implied Turkish support for armed opposition, this suggests that the Assad government will struggle to contain protests in major cities in the 3-6 month outlook and increases the risk of a civil war beyond that timeframe.

A Syria expert at Exclusive Analysis who declined to be identified due to the sensitivity of the topic said he expected “a steady erosion of the power of the Syrian army and a steady limiting of the territory that it can access.”

“The way it’s heading is more towards full-scale civil war which draws in the intervention of regional actors.”

But Shashank Joshi, an associate fellow at Britain’s Royal United Services Institute, told Reuters “the army has a lot left in it. It still has enough elite units and has enough size and capability to still mount severe violence.”

“The question is, the bits that it can’t hold, are they ever going to be retaken by the government? And my suspicion is, they are not,” he said, referring to areas around the southern city of Deraa and the central city of Homs.

Joshi expects “a stalemate” between the two sides where the government cannot retake land it has lost but the insurgents cannot challenge the army in areas they would like to take.