Trending

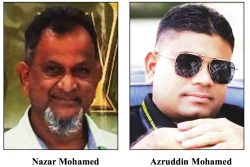

Roshan Khan says questioned in New York about Mohameds

Two bandits shot dead during attempted robbery at Chinese supermarket

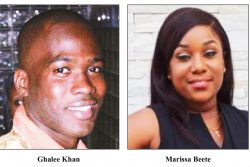

Ghalee Khan held over murder of ex-paramour

Killing of bystander by police triggers Linden protests

President denies gov’t targeting Mohameds

SOCU arrests two Essequibo gold miners in smuggling probe

Foreign Ministry rejects Maduro’s submission to UN Secretary General on border controversy

Protester shot dead in Linden, President appeals for calm

Contract of GECOM legal officer not renewed