This was no holiday trip. Terry basically rode each day until dark, often sleeping in a tent, got up the next day and rode again, on and on. He wasn’t out there to see the sights or to prove his endurance; propelled by the mental health problems of his brother, Terry’s mission on the ride was to draw attention to the myths and misunderstandings about the disease.

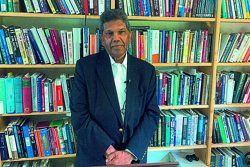

Living in New Jersey, he had created an organization called Quiet Noise to try and change negative attitudes to mental illness, and he was tackling this forbidding trip not as Terry Ferreira, but in his Quiet Noise persona. (See box)

Going back to March 1996, preparing for the ride and dealing with officialdom in Guyana, Terry had almost given up on the venture. “That’s impossible,” he was told in several quarters. “The terrain doesn’t exist that would allow you to do that journey riding a bicycle. No way.” But an enterprising cousin, nature photographer Bobby Fernandes, figured out the route for him and the game was on. Ferreira, by then living in the USA, was on this “impossible” ride with no entourage and no support group.

“He would ultimately ride alone, but for the first part of his trip he was accompanied by his younger sister Jackie. They flew to Kaieteur, camped overnight and then started a four-day trek to the Brazilian border near Orinduik from where they eventually reached the first proper roadway. But on only the ninth day of the ride, disaster struck. Negotiating a rickety bridge over a dry Brazilian river bed, Terry’s front wheel caught in a crack in the planking and he fell, 15 feet, breaking his left arm close to his wrist. It appeared Terry’s ride was over; a broken wrist meant weeks of recovery.

With no medical facilities nearby, a place was found to store Terry’s bike and an ambulance took him to the Santa Elena Public Hospital in Venezuela to have his arm set. But at the hospital, a young Venezuelan, Enrique Ramirez, hearing Terry’s story, came to his aid. Said Terry, “I’ll never forget Enrique.

He played a huge part in getting us out of the Amazon the next day, a Sunday, seeing us off to Caracas, and then Jackie to Miami and me to Trinidad to recuperate at my sister’s house. Not only that; he told me, ‘When you return I’ll ride across the country with you.’” Sitting in Venezuela, with his arm in a cast, Terry, the eternal optimist, was already thinking of resuming the Quiet Noise ride.

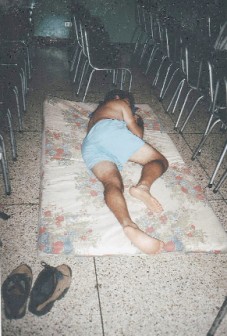

In Trinidad, Terry was in the care of his sister Julia Ann. “She was wonderful, but with this huge cast, up to my shoulder, I began to suffer terribly from panic attacks,” he said. “It became difficult to stay indoors, or even to have a barber’s cloth placed around my neck, or to pull shut a shower curtain to shower.

“Sleeping was difficult; my sister Julia Ann must have thought I was going crazy; she lectured me into not returning to the ride after my rehab. However, I always kept Enrique’s positive approach in mind; ‘when’ you return.” Six weeks after he crashed, Terry hooked up with Enrique in Venezuela, at the very hospital where they had met. It was an emotional time: “Enrique was a man of his word.

Until that day he hadn’t done any serious biking, yet in less than a month we rode completely across Venezuela. In that time, I was able to pick up some Spanish and to regain control of my ego; we laughed a lot, although riding with a soft cast on my left forearm was never going to be easy.”

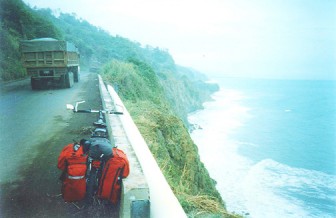

With Venezuela under his belt, Terry waved goodbye to Enrique and veered north, riding through Colombia, Panama, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Honduras, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Mexico. In the USA, his wheels turned through Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Florida, Georgia, South and North Carolina, Virginia, DC, Delaware, New Jersey, and New York, then across the Thousand Islands Bridge into Ontario, and down to Niagara Falls. Although this ride is not widely known, it was a tremendous display of perseverance, physical endurance and mental persistence, never done before and not since. It is a singular achievement, and it was done by a singular Guyanese.

In all that time, close to 7 months on the ride, Terry never got ill and never felt threatened. He said, “I had an ATM card but very little cash – food in Central America was extremely cheap – and I never had any sense of danger. Mind you, I took precautions.

“When I slept in my tent, I would have a string on my toe connected to my bike outside. Also, I stayed away from exotic food; I ate a lot of fruits and fried chicken for protein, and I filled up on coconut water and fresh fruit juice all the time.” However, he recalls one occasion when a group of heavily-armed soldiers in Colombia had him a bit nervous. “Late one day, they stopped me at a road block and sent me down this little trail to God knows where – not much conversation; getting dark; I was wondering if this was it. As it turned out, the road led to a nice hotel; quick time, I was kicked back watching CNN.”

The Latin people he met along the way were sometimes shy, then curious, then friendly. He would frequently end up being interviewed for radio and newspapers, and people would often ride along with him briefly for company. Said Terry, “The difference between the people in Central America and those in the US was that the Latin people would give of themselves, or their time – they would interact. The people in the US would give you money.

A guy in a Benz drove up to me one day – he had heard about the ride on the radio – and said he wanted to support me and offered to buy me lunch. Mind you, the Americans would support you strongly in other ways, such as backing your organization publicly.”

What did he travel with? “In Guyana and Brazil where the passage was mostly jungle, Jackie and I carried dehydrated meals, a tiny water purifier, a single-burner stove, a change of clothing, a pair of clip-on bike shoes and a pair of hiking shoes each, two spare tyres, five tubes, a spare chain, patches, a plastic bowl and a spoon each, a small First Aid kit, and two single-person tents.

Her load was nearly 20 pounds, and mine almost 40. When I restarted in June, and you could say in civilization, I was able to get rid of a lot of stuff and my load was now 15 pounds – no stove, no purifier, etc. Of course I always carried my tent.”

How did he persevere? “Every day brought its own set of hardships, and those hardships would trump all other hardships. It was always about what was pressing at the time. One would assume that riding in the tropical heat or rain, or the mountains, or the snow in North America, would be the hardest.

Not so; the hardest thing to do was not quit. The rest of the problems came and went, but quitting while in Central America always harassed me. Every day that thought rode with me as sure as my name did. I had a credit card. I could go to the nearest airport, and two hours later I would be in Miami sitting with Jackie in a nice restaurant. That option to quit; I had to fight that every day.”

Apart from the attention to Quiet Noise, what did he get from that long grind? “The ride taught me plenty about myself; like how to traverse my fears; how to say goodbye to what was once my normal life; how to consider myself already dead thereby allowing me to see my current life as a privilege.

Furthermore I realized if I looked people in the eye and paid them due respect, that nine out of ten times they would respect me, perhaps befriend me, and even offer me their nicest bed to rest my battered bones. I learned that there isn’t a devil; just egos gone astray. I learned, too, that it is possible to travel on a bicycle from Guyana to Canada without being robbed.

I know that people are mostly good, at least those living between Kaieteur Falls and Niagara Falls. I know how marvellous a bicycle is, and that I should never pee uphill.”