TEHRAN (Reuters) – The storming of the British Embassy in Tehran has bared a rift in Iran’s ruling elite with conservative hardliners pushing Iran towards global isolation as they manoeuvre for the upper hand over President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad ahead of elections in 2012.

Britain closed its embassy after Tuesday’s incursion by hardline youth and expelled all Iranian diplomats from London. The fallout for Tehran spread when several other countries recalled their envoys, including France and Germany.

The assault occurred a few days after the hardline-dominated parliament passed a bill obliging the government to downgrade Britain’s diplomatic status and expel its ambassador in reprisal for fresh sanctions imposed on Tehran over its nuclear activity.

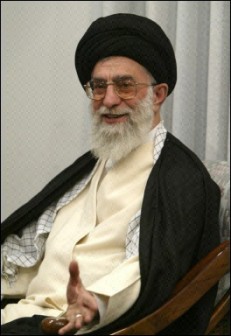

Western diplomats and some local analysts believe the embassy raid was quietly orchestrated by hardline isolationist elements of Iran’s factionalised power structure loyal to the clerical supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

The attack was led by members of the radical Islamic Basij militia and two hardline rivals of Ahmadinejad publicly endorsed it, comments that clashed with an apology by his foreign ministry.

Their vocal support reflected the loyalty of Tehran Mayor Mohammad Baqer Qalibaf and speaker of parliament Ali Larijani to Khamenei, who has not yet spoken about the events.

“The attack clearly displays the internal political rift … Foreign pressure has deepened the rift and there is no unity on the response,” said an Iranian analyst who asked not to be named due to security sensitivities.

High-level discord in Iran has never been so public but has little to do with its nuclear row with the West or with the pro-reform opposition, which rejected President Ahmadinejad’s 2009 re-election as rigged.

‘Taking off gloves’

Ahmadinejad has come under heavy criticism from hardline conservatives and powerful clerics for unorthodox economic policies seen as inflationary, including spending petrodollars.

Ahmadinejad has angered hardline elites further over his efforts to wrest more control of security and foreign affairs from the clerical establishment under Khamenei.

“Now the hardline rival camp has taken off the gloves … This [embassy] attack was a warning to Ahmadinejad’s government … He will be very busy with this created international crisis,” Sadeghi said.

It would help ruin the credibility of Ahmadinejad’s camp ahead of parliamentary elections in 2012, analysts say.

“Despite his harsh anti-Western rhetoric, Ahmadinejad is open to engagement with the West … He lost his legitimacy at home after the 2009 vote; by engaging with the West, he seeks international legitimacy,” said analyst Mohsen Sadeghi.

“A power struggle between top leaders could shake the Islamic Republic to its foundations… [and] weaken Ahmadinejad globally.”

Iran’s elite Revolutionary Guards and Basij militia have distanced themselves from Ahmadinejad and remain fiercely loyal to Khamenei.

Some analysts say Iran’s increasing isolation will have a negative impact on international efforts to push Tehran into suspending sensitive nuclear activity, which the United States and its allies say is aimed at building bombs.

Iran, the world’s fifth biggest oil exporter, says it only wants nuclear technology to generate more electricity for a rapidly growing population.

“This isolation will not help the West … Iranians will accuse the West of not wanting a political solution for the nuclear dispute,” said analyst Hamid Farahvashi.

The storming, analysts say, resembled the seizure of the US Embassy in Iran shortly after the 1979 Islamic Revolution when hardline students held 52 Americans hostage for 444 days – goading Washing-ton to sever diplomatic ties with Tehran.

Normally, the withdrawal of ambassadors is dramatic diplomatic move – but not for Iranian hardliners.

“Hawks in Iran and in the West favour tension and crisis … This could be a start,” said political analyst Ismail Boy at Turkey’s Kadir Has University.

Western powers have recalled ambassadors from Tehran on three previous occasions: in 1980, when US diplomats were held hostage in Tehran; in 1989, when Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini issued a fatwa calling for the death of author Salman Rushdie for alleged blasphemy of Islam; and 1997, when a Berlin court ruled that Iran’s top political leadership was involved in organising the 1992 murder of four Iranian exiles in Germany.

In all three instances, the envoys returned to Tehran within weeks and normal relations resumed. But there might be a different denouement this time.

Crisis, isolation

serves hardliners

“Some Iranian hardliners might even welcome such a crisis with the international community to unite the nation and divert attention from political infighting and the nuclear dispute,” said analyst Boy.

“More isolation and harsh responses gives an upper hand to hardliners… and [helps them] militarise the atmosphere.”

Iran however will want to avoid any escalation into a war with the West that could be difficult to win and might threaten the clerical establishment’s existence, analysts say.

“They do not want a confrontation … Iranians know that a serious confrontation would run counter to the establishment’s interests,” said Hamid Farahvashian. “In charting its next steps, Tehran must take into account the impact of such moves on its relations with its Gulf neighbours.”

“Iran’s muscle-flexing has limits, has a ceiling which it cannot go over,” said a senior Western diplomat in Tehran.

Many ordinary Iranians were shocked by the crisis with Britain and fear they will suffer. “It is not good to sever ties … More isolation means more economic pressure … We cannot tolerate it,” said housewife Maryam Shabani, 35.

Some analysts say the United States and its allies are worried about last-ditch Israeli military action against Iran in the absence of trouble-shooting diplomacy, and to ward off that risk they have resorted to stiffening sanctions.

“By putting more pressure on Iran, the West wants to avoid unilateral Israeli military action against Iranian nuclear sites,” said another analyst who asked not to be named.

“The British authorities were looking for an excuse to put more pressure on Iran. That is why their reaction was harsh.”

Analysts say Tehran is also nervous about a possible spillover of unrest from the Arab world. Iranian leaders have made clear they will not tolerate any renewal of anti-government protests, which died down a few months after the 2009 election.