CHICAGO (Reuters) – A U.S. scientific advisory board yesterday asked two scientific journals to leave out data from research studies on a lab-made version of bird flu that could spread more easily to humans, fearing it could be used as a potential weapon.

The U.S. National Science Advisory Board for Biosecurity has asked the journals Nature and Science to publish redacted versions of the studies by two research groups that reportedly created forms of the H5N1 avian flu that could easily jump between ferrets — typically considered a sign that the virus could spread quickly among humans.

Both journals said in separate statements they are working with the advisory board and taking the matter seriously, but they chafed at the notion of scientific censorship.

The bird flu virus is extremely deadly in people who are directly exposed to infected birds, but so far, it has not mutated into a form that can pass easily from person to person.

According to the journals, two research labs have submitted papers showing how to make the virus more transmissible in humans, and the NSABB, an independent expert committee that advises the Department of Health and Human Services and other federal agencies, wants to keep this information from falling into the wrong hands.

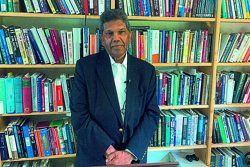

The articles involved work done by Yoshihiro Kawaoka, a University of Wisconsin-Madison scientist, and Dr. Ron Fouchier and colleagues from the Erasmus Medical Center in Rotterdam.

The National Institutes of Health said in a statement the HHS agreed with the panel’s assessment and provided the journals with non-binding recommendations to withhold key elements of the studies, but said the government is working out a system to allow secure access to the information to those with a legitimate need to see it.

The journals are objecting to the request, saying it would restrict public access to information that might advance the cause of public health.

“It is essential for public health that the full details of any scientific analysis of flu viruses be available to researchers,” according to a statement issued by Dr. Philip Campbell, editor in chief of Nature.

“We are discussing with interested parties how, within the scenario recommended by NSABB, appropriate access to the scientific methods and data could be enabled.”

Dr. Bruce Alberts, editor in chief of Science magazine, said in a statement the advisory board asked the journal to delete details on the scientific methods and specific mutations of the virus before publishing an article by Fouchier and colleagues.

“The NSABB has emphasized the need to prevent the details of the research from falling into the wrong hands,” Alberts said in a statement.

He said many scientists who study influenza have a need to know the details of the research in order to protect the public. He said the editors at Science are evaluating how best to proceed.

“Our response will be heavily dependent upon the further steps taken by the U.S. government to set forth a written, transparent plan to ensure that any information that is omitted from the publication will be provided to all those responsible scientists who request it, as part of their legitimate efforts to improve public health and safety.”

Other researchers said the mutations described in the papers were not unusual or unexpected, and several voiced concerned over government-imposed censorship on science.

“It is a very worrying idea that information from this type of work may be restricted to those that ‘qualify’ in some way to be allowed to share it,” Professor Wendy Barclay, chairwoman in influenza virology at Imperial College London, said in an e-mailed statement.

“Who will qualify? How will this be decided? In the end is the likelihood of misuse outweighed by the danger of beginning a Big Brother society?”