Two related Caribbean festivals are again topical at this time of the year. It is the season of Diwali, one of the largest traditional festivals in both Guyana and Trinidad and Tobago. The annual Ramlila performances ended in Trinidad on Sunday, October 9, and Diwali will be celebrated in both countries on October 26. These are both religious festivals which are very important to sacred Hindu ritual and worship, but which also have a marked public outreach with highly spectacular performance.

They are closely related, so that Ramlila is part of the Diwali season in Trinidad and Tobago. While it is a significant event in itself, it heralds the larger festival, normally coming some three weeks before it and signaling the beginning of the ‘season’. But the festivals are related in a number of other ways within and without Hinduism. In their popular performance and outreach they both take the form of the Caribbean carnivalesque tradition since they utilise street theatre, costume construction, costumed masques and outdoor public performance.

They are closely related, so that Ramlila is part of the Diwali season in Trinidad and Tobago. While it is a significant event in itself, it heralds the larger festival, normally coming some three weeks before it and signaling the beginning of the ‘season’. But the festivals are related in a number of other ways within and without Hinduism. In their popular performance and outreach they both take the form of the Caribbean carnivalesque tradition since they utilise street theatre, costume construction, costumed masques and outdoor public performance.

They use these means to relate with and to appeal directly to the population at large since their purpose is deeply religious and they use these forms of public exhibition to broadcast their message. Ramlila and Diwali are conducted through religious devotion, worship and ritual among the believers and then extended into theatre and spectacle, public expression of Hindu mythology and belief through symbolism and spectacular exhibition. A very significant factor is the way Diwali has been affected by time, tradition, cultural change and the force of the popular culture.

In 2011, this ‘season’ started at the beginning of October with the Ramlila performances running in Trinidad from October 1 – 9. This epic drama, sometimes spelt “Ram-leela” and called “ramdilla” in Creole by the villagers, is the oldest surviving theatrical performance tradition of the Hindus in the Caribbean, having been brought over from India under indentureship. Unlike the public outreach of Diwali, however, it was designed and is performed for a Hindu audience who are believers and most likely already familiar with the doctrine. It reaches out to devotees, but its purpose is didactic, to teach the villagers about the principles of the religion and to dramatise the contents of the holy book, The Ramayana, for those who had not or could not read it.

It is the dramatisation of the story of Lord Ram, Ram-lila being translated as “Ram’s play” and tells the story of his life concentrating on the period of his exile from Ayodhya, detailing his epic battles with Rawan of Lanka, ending with his defeat of the demon king and his triumphant return to the kingdom in Ayodhya. While the tradition did not survive in Guyana, it is performed annually two to three weeks before Diwali at about 35 locations in Trinidad, mainly in Central and South, and highly concentrated around Chaguanas and Couva.

These performances are dated back to 1882 and Dow Village is credited as having the oldest surviving play. But the village of Felicity has risen to be the most famous site, no doubt aided by Derek Walcott’s tribute to it in his Nobel Lecture in 1992. Felicity can speak for itself, however, with three locations hosting simultaneous performances within walking distance of each other.

This cultural form is the greatest folk traditional theatre produced and performed by villagers in the Caribbean. It is a grand epic performed in an open field or the village playground, so it has a stage almost the size of a football field with the audience standing by the barriers around it. This is the longest play in the world, lasting for some 40 hours and taking 10 nights of performance. Its similarities with Diwali include its use of the same elements of drama, symbol, myth and theatrical spectacle. The high-point of the dramatisation comes at the end with the defeat of Rawan and the burning of his effigy. This is a huge image standing 30 feet high into which Ram and his soldiers shoot arrows and it is burned; the drama closing with the impact of this towering image engulfed in flames. That is a symbol of Ram’s triumph over evil, with the message of light overcoming darkness. Then the finale has a truck driving through the village streets followed by a joyous crowd, which then allows the audience to participate in the celebration of Ram’s return home as king.

While the similarities are in theatre and spectacle, one of the main differences is that Ramlila uses a written script while Diwali has none, depending instead on symbol and image. The script is read (or recited) by a knowledgeable narrator while the story is acted out by the villagers. It is taken from the text Ramcharitamanasa by Tulsidas (1543-1623) which is his translation of the original Ramayana by Valmiki. He adapted it from the original Sanskrit into a language that the general populace would understand for the purpose of teaching them. In this way it is also different from Diwali in that it is not aimed at non-Hindus, but to better inform those who already believe. For this purpose the narrator brings into his narrative text explanations and comments which include topical and local references to emphasise faith, virtue and the qualities of Ram.

The reasons for and the date when this folk drama became extinct in Guyana are still generally unknown and undocumented, while it flourishes in Trinidad. But despite this there is still much talk about additional efforts to sustain it in the island, including the building of new sites and the upgrading of the present ones. Recent speeches from politicians, Minister of Local Government Rudradath Indarsingh (Shastri Boodan, Guardian, Oct 14, 2011) and Prime Minister Kamla Persad-Bissessar included promises to upgrade facilities at California and to build a permanent Ramlila Centre on the grounds of the already existing Diwali Nagar in Chaguanas (Laura Dowrich-Phillips, Caribbean Beat, Sept-Oct, 2011). Meanwhile, Walcott’s Nobel remarks have helped to bring it to world attention and boost tourism.

Although there have been occasional reports about a revival in Guyana, little is known of this. The most telling event where any revival is concerned was the stage version of Ramlila performed by the Nritya Sang of the Guyana Hindu Dharmic Sabha directed by Dr Vindhya Persaud in 2009. The dance drama was choreographed by Dr Persaud and Trishala Persaud and was one of the best theatrical productions in Guyana for that year.

While Diwali is a national festival in both Trinidad and Tobago and Guyana, the public impact in Guyana, where it tends to be much livelier and more popular, is greater. However, it has enough public outreach in Trinidad for the Prime Minister to have expressed regret (Express, October 18, 2011) that Diwali this year will be restrained by the imposed curfew now in force.

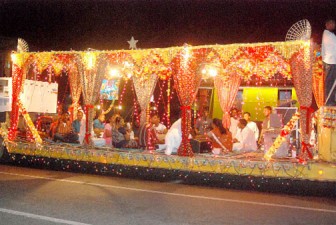

The grand annual Diwali motorcade in Georgetown surpasses anything else in the Caribbean as an event of street theatre to celebrate a religious festival. In Guyana its popular appeal is exceeded only by Christmas and Mashramani, and only the latter has a greater turnout of crowds on the streets. This motorcade is important as public outreach because it appeals to non-Hindus with exhibitions of symbols which express some of the messages of Hinduism in a popular way. Spectacle is employed in the display of lighted diyas, which are at the same time symbols and a ritual of religious faith. While for most Hindus the goddess Laxmi is invited to enter their homes and bring blessings of prosperity and enlightenment, for other viewers of the lights it is a sight of beauty and creativity.

As in Ramlila, the lights of Diwali also express mythology because they are used to dramatise the same story of Lord Ram. Almost in neat chronology, Diwali takes up the story where the village drama leaves it – the return of Ram home from exile. Because he returned on the darkest night of the year, the people lit rows of diyas to guide him home while celebrating his triumph and the conquest of good over evil and light over darkness.

The festival of lights is further driven by theatre because of the several stage performances across the country involving music, dance and small dramatisations in skits with topical and moral messages. Over the decades, Diwali has driven and sustained Indian dance and has been one of the greatest vehicles for its popularity and significance in communities around the country, as well as the overall strength of Indian dance nationally. There is now a grand annual show and public exhibition led by the Maha Sabha’s Nritya Sang at Guyana’s national stadium.

Creativity continues in other forms of public exhibitions than the designed lights of the motorcades. On a minor scale there is the Rangoli, which basically is the art of drawing images and motifs on the floor and walls of one’s home using different coloured powders. Designed with a beautiful combination of various colours, the Rangoli images create an enchanting piece of art and stands for a sign of welcome. The main purpose of making Rangolis in Diwali is to welcome Goddess Laxmi, the Goddess of wealth, to individual homes apart from warding off the evil eye.

The patterns are made with fingers using rice powder, crushed lime stone, or colored chalk. They may be topped with grains, pulses, beads, or flowers.

At the same time cultural change has had positive and what may be considered unwanted effects on the festival. Creativity has expanded in the motorcades including the resurrection in Georgetown of practices that had previously faded in Guyana or were confined only to the country areas.

Where the designs in the past were created purely out of arranged lights and lighting effects, the several tableaux now include live actresses riding on the vehicles in the motorcade. While lights predominated in the city, there were groups of persons in carts or on vehicles on the Essequibo Coast providing music, singing and live costumed figures representing the Hindu pantheon. These have now become common features in the capital where they were not in previous years. Actresses now play roles in the tableaux along with a vast increase in artistry employed to make larger images of the gods and symbols, thus moving closer to the costume creations of Trinidad. But while live singing is now mixed with recorded music, diyas are gradually being replaced by electric lighting.

On the other hand the vastly effective popular impact in Guyana has given rise to what many devout Hindus will regard as unwanted developments. These have included ugly, unruly and dangerous elements that escalate in Alexander Village with wild street revelry on Diwali night rudely disrupting worship at the mandir. However, these were not acts of anti-Hindu venom as the victims saw it, they were the effects of cultural change and the popular culture carelessly overdone in Alexander Village. While the acts in that area were more reckless, the phenomenon was not far removed from what happens today at Phagwah in Trinidad. The Holi celebrations in open fields and on the streets during the day turn into carnival-styled street fetes as the afternoon moves into evening with rum and beer drinking, quite contrary to the holy script.

That is the force of the popular culture in the Caribbean where street parties and limes are closely allied with street theatre. While the police have brought back peace and sanity to Alexander Village, elsewhere the revelry on Diwali night continues in less offensive fashion without the ugliness and rank indiscipline. These are marks of cultural change and contemporary cultural trends that cannot be prevented. They can be placed alongside the many other types of cultural change taking place even within accepted practice within the festival itself. Ironically, also, these marches of the popular culture are consequences of the successful public outreach long cultivated by Diwali.