The Darking Thrush

I leant upon a coppice gate

When Frost was spectre-gray,

And Winter’s dregs made desolate

The weakening eye of day

The tangled bine-stems scored the sky

Like strings of broken lyres,

And all mankind that haunted nigh

Had sought their household fires.

The land’s sharp features seemed to be

The Century’s corpse outleant,

His crypt the cloudy canopy,

The wind his death-lament.

The ancient pulse of germ and birth

Was shrunken hard and dry,

And every spirit upon earth

Seemed fervourless as I.

At once a voice arose among

The bleak twigs overhead

In a full-hearted evensong

Of joy illimited;

An aged thrush, frail, gaunt, and small,

In blast-beruffled plume,

Had chosen thus to fling his soul

Upon the growing gloom.

So little cause for carolings

Of such ecstatic sound

Was written on terrestrial things

Afar or nigh around,

That I could think there trembled

through

His happy good-night air

Some blessed Hope, whereof he knew

And I was unaware.

Thomas Hardy

We have previously observed that the great poems identified as belonging to and identified with ‘seasons’ such as New Years or Christmas are memorable because they do much more than celebrate the season. Some of them do not even do that. They endure because they introduce some profound meaning or use the season as an artistic base from which to engage issues of social, political or human importance.

Thomas Hardy’s The Darkling Thrush (1900-01) is such a poem. We made reference to it in 2011 as a New Year‘s poem with deeper meaning. It might not be in the same bracket as TS Eliot’s Journey of the Magi, the best so-called Christmas poem, or Robert Burns’ Auld Lang Syne, but, like Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s I Heard the Bells on Christmas Day, it introduces a discordant note into the celebration of a seasonal event.

Thomas Hardy’s The Darkling Thrush (1900-01) is such a poem. We made reference to it in 2011 as a New Year‘s poem with deeper meaning. It might not be in the same bracket as TS Eliot’s Journey of the Magi, the best so-called Christmas poem, or Robert Burns’ Auld Lang Syne, but, like Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s I Heard the Bells on Christmas Day, it introduces a discordant note into the celebration of a seasonal event.

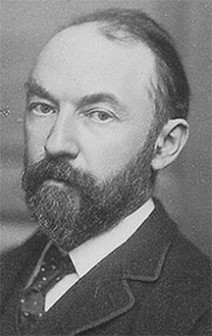

It was written by Thomas Hardy (1840-1928), English novelist and poet, known for his rather tragic disposition exhibited in many of his novels. Two of these tragedies, Tess of the D’Urbevilles and Jude The Obscure generated a great deal of controversy and moral indignation in his time because they offended the Victorian sense of modesty and propriety. Tess is the tragedy of a wronged woman which defended its heroine against the conventional morality, sensitivities and Christianity. Jude is the pessimistic tragedy of an “obscure” country artisan doomed to defeat and non-achievement. Its sexuality and seeming positions against the Christian church and marriage offended. It was renamed ‘Jude the Obscene‘ by its critics according to Wikipedia.

Yet Hardy celebrates the English Wessex country, its provincial life and traditions, immortalising them in literature. A good example of this is found in another novel with a bleak, deterministic outlook, The Return of the Native, which pits the individual against a seemingly hostile social environment that works against the protagonists. Yet it documents interesting customs and traditions in Wessex. He gave up fiction writing after the controversies and focused his attention on poetry. But, although trained in architecture, he gave it up to become a professional writer because of the success, including financial success, of his novels, many of which were first serialised in a magazine, after the fashion of the great Charles Dickens.

The Darkling Thrush is Victorian but steeped in the Romantic Age that went before. Like the Romantics, the poet is influenced by nature which serves as spiritual guidance and inspiration. He takes some heart from the singing of a bird (as in Keats’ Nightingale) which is able to transform his mood from depression to hope. The poet looks out in the ‘dead’ of winter and sees a landscape that reflects gloom and bitterness, but is moved by the joyful singing of a thrush which resists the darkness.

The poem is linked to the New Year because Hardy wrote it on December 31, 1900 and first titled it By The Century’s Deathbed. It was published on January 1, 1901 as a New Years Day poem. Further to that, it describes the severe winter landscape covered by a sheet of snow, the skeletal trees like “tangled bine-stems” and the frost as “the Century’s corpse outleant.” The poem is describing the turn of the century; the end of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth, and it is as if the corpse of the old century is stretched out. The description abounds in images of death: the frost is “spectre-gray,” the day’s “eye” is “weakening” (it is afternoon and getting dark), the people are “mankind that haunted nigh,” the cloudy canopy is a “crypt” and the eerie howling wind a “death lament.”

Everything around, both human and natural, is “fervourless” and gloomy. The bird with his spirited song is the only thing with a positive glimmer of “Hope.” Yet this is a very lyrical poem, against the grain of Hardy’s usual pessimism. It is so because of the Romanticism and the bird’s influence expressed in the remarkable images of “joy illimited” and the “blast-beruffled plume” of the thrush’s effort. But the lyricism is also in the even and lively metre.

Note, however, that the poet still does not quite share the bird’s ecstasy. He sees “little cause for carollings” in all “terrestrial things” and is “unaware” of the “blessed Hope” that the bird seems to know about. He sees a very bleak prospect dominated by the death of a century, not by any bright spirit in the new one. This is where Hardy falls in line with the rise of Modern Poetry following the Victorian. At that time the poets saw the age as lacking in spiritual strength. This drove themes and preoccupations for the whole first quarter of the twentieth century and was partly responsible for the new poetic forms that brought in “modern” and “modernist” verse. Poets, led by TS Eliot, sought new ways of bringing these out.

That is what makes The Darkling Thrush stand out. Its style is Victorian, not modern, its philosophy Romantic, but clearly drawn to the modernist concerns about spiritless, directionless, frail and hopeless mankind. This mix of the old and the new help to make it a memorable poem about the changing of the year.