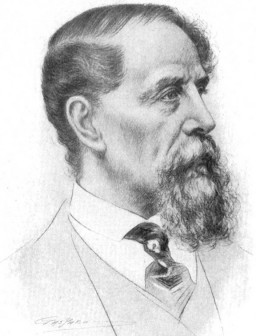

Dickens (February 1812-June 1870) is worth celebrating because of his achievements as the foremost Victorian novelist and one of the greatest of all English writers. His work is of universal and lasting relevance and is in demand today as much as it was during his lifetime. He is extremely popular and very well known and has the distinction of producing books that, according to the BBC, never went out of print from the time they were published to the present. Yet, these novels have been best-sellers because they mix popularity with high critical acclaim. Dickens is respected for the profound treatment of several issues in literature of considerable weight, demonstrating a command of the craft of fiction.

He enjoyed what some great writers of the past missed, viz, popularity, critical acclaim, wealth and celebrity status during his lifetime. That is testimony to his excellence, immediate relevance, and accessibility. The nineteenth century audience could identify with several appealing reference points as he reflected the Victorian society. However, as eloquently as he could speak to his own time, his preoccupations are timeless. The term ‘Dickensian‘ carries some meaning in literature today. It relates to his sharp sense of the grotesque, his memorable characterisation which has left English literature with a number of enduring archetypes and popular Dickensian characters. Also very strong among his attributes is the obvious fact that his work is exceptionally entertaining.

Dickens grew up mostly in London, surviving experiences of a struggle against poverty, working as a boy in testing conditions in the growing industrial city. He went to a good school which he had to leave prematurely to work to help bail his family out of debt. He variously worked in a factory, became a legal clerk and a reporter, experiences which vividly informed his presentation in fiction of the grime of London, the appalling conditions of child labour, crime, and the unending quagmire of litigation and injustice. His personal observations of these were fictionalised in Oliver Twist, David Copperfield, and Bleak House among others.

The nineteenth century in Europe was characterised by the forward march of industrialisation in its major cities, including Dickens’ London. That environment aptly illustrated the expansion of the working class on whom industrialisation depended for a source of cheap labour. Conditions and the quality of life worsened in the cities, which Romantic poets saw as hostile (William Blake) and a thing of beauty (William Wordsworth). Vict-orians continued the view of the urban environment as a battleground for “nature red in tooth and claw” (Tennyson), and the whole society as morally perplexing and socially unjust. Dickens was convinced of the truth of all of this as he lived through it as a boy and adolescent, thereafter creating fiction which warned readers against the society’s traps and dangers while entertaining them with the colourful characters that it created. He seems to have had particularly strong feelings about poverty, injustice and class, the law and a depressing judicial system, and a range of corrupting influences which he deals with in Great Expectations, David Copperfield, and quite bitterly in Bleak House. It appears Dickens had as many quarrels with the capitalist system as did Karl Marx who eventually released his monumental study of it in 1848.

Charles Dickens’ contribution to literature includes the way he brought that environment and all those issues to us in tragic as well as delightful fiction. His tragic sense and profound treatment are celebrated, but the commemoration is also worthy because of the way he entertains.

His strong awareness of an audience is worthy of celebration. He first began writing novels by serialising the stories in magazines, developing and releasing them chapter by chapter. That accounts for the high dramatic quality that is present in some works. Chapters end on a sharp dramatic note exploiting suspense and anticipation, since he had to sustain the interest of the readers in engaging the next episode. He created what became known as ‘cliff hangers.‘ Of equal relevance is the practice that he also developed of giving public readings. These were theatrical, and he even employed an actress to assist in the performances. The readings had a continued popular demand, so that even when he was ill late in his life he had a heavy performance schedule.

Some of the novels are included in the canon (a term that is somewhat discredited these days) – the all-time great works of literature. Novels like A Tale of Two Cities reflects historically on the French Revolution, perhaps the most ‘Romantic’ of his novels, linking Paris to London in an intertwining tale of politics, romance, terror, tragedy and rebirth. A Christmas Carol is the greatest literary work about Christmas and the spirit it is supposed to inspire is pitted against capitalist greed, exploitation and the suffering of low income families. It is a comedy of reformation, self knowledge and generosity. Great Expectations remains one of the most memorable works about the corrupting influence of wealth, class and snobbery, the worthlessness of glamour and appearances, and the criminal underworld. It leaves readers with a deep awareness of what are genuine human values.

Some of the best known archetypes are found in these novels. Ebenezer Scrooge the hero of A Christmas Carol placed a word in the common English language. ‘Scrooge‘ became the archetypal character for stinginess and joylessness and the word used to describe such a person. Equally identifiable is his dismissive phrase “bah, humbug!” Oliver Twist became an archetype for exploited orphans in a world of poverty, and so has his famous plea “may I have some more?” as an expression of hunger and ill treatment. The Artful Dodger from the same novel is an unforgettable character representing pick-pockets. Such other phrases as “Barkis is willing,” and the economics of Mr Micawber provide some of the most memorable words, sayings and archetypes in the English language.

These are also connected to the Dickensian grotesque in which many famous characters are caricatures, representing types. But at the same time they are very deep studies and evoke pathos because of what they reveal about the human condition. These are the cases found in such examples as Miss Havisham in Great Expectations, an archetype for women jilted at the altar, whose caricatured eccentricity provides humour but who invites a more sympathetic study of an embittered woman seeking revenge against men and the world. The convict Magwich in the same story seems a grotesque demon in the eyes of a small boy, and in the eyes of society is condemned and exiled from the human race. But Dickens enriches him with human values superior to many of the ‘better’ characters. He has good intentions of rewarding kindness and doing something constructive and helpful with his wealth.

The everlasting appeal of the novels is re-emphasised in the many conversions into musicals in the theatre and feature films. The musical Oliver took its place among the celebrated successes while the BBC announced that Great Expectations is to be filmed yet again. A Christmas Carol has been an inspiration for several versions and adaptations including dramatisation for the stage, while a number of notable actors such as Emlyn Williams have imitated the novelist in their performance around the world of dramatic readings from his works.

Charles Dickens’ work is naturalistic and studies Victorian society in a way that recommended it overwhelmingly to his contemporaries. But his themes, images and theatrical creations, his literary genius and narrative craftsmanship have endeared him to audiences and kept his works alive and relevant to the social and human consciousness of the entire two hundred years since he arrived on earth.