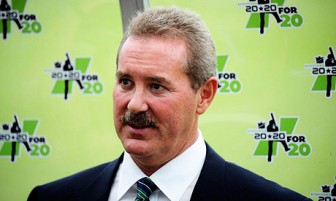

Allen Stanford’s attorneys on Wednesday began presenting their defence in his $7B fraud case and set about on Friday trying to blame his top deputy James Davis as around 40 investors listened intently and hoping that they would someday be able to retrieve their investments. The trial enters its fifth week on Tuesday.

Reuters reported on Friday that defence lawyers made a case for Stanford’s innocence in a courtroom filled with people who said he had stolen millions of dollars of their savings. During a break in the testimony, Angela Shaw, founder of the Stanford Victims Coalition, told Reuters that three years without restitution had made a mockery of those people. Prosecutors have been contending that Stanford stole money deposited at Stanford International Bank in Antigua and blew it on girlfriends, mansions, private jets and yachts. Stanford, 61, has pleaded not guilty to 14 counts, and his defence lawyers have argued that he was not responsible for any fraud because he left business decisions to his subordinates. Attorneys have said they will show that Stanford’s former top deputy Davis had oversight of funds invested in Stanford International Bank. Davis has pleaded guilty to fraud and testified against Stanford.

Reuters said that on Friday, former Stanford aide Linda Wingfield testified that Davis had fought her efforts to implement policies to control company expenses. ‘He would ignore the policies,’ she said. Testifying by video from Orlando, Florida, because she was unable to travel to Houston, Wingfield told the court that she had expressed concern at the time that Davis had sole responsibility for certain internal audits of operations at Stanford International Bank. Under cross examination by the US government, Wingfield said that when she emailed Stanford laying out concerns about Davis, Stanford said she should not have put them into writing. Davis was a star witness during the prosecution, which rested its case on Wednesday. He told the court that he and Stanford ‘cooked the books’ of Stanford’s bank and regularly withdrew millions of dollars from a secret Swiss bank account that comprised investor money. But, under cross-examination by Stanford lawyer Robert Scardino, Davis admitted that he was a liar and a serial adulterer and that he had committed fraud. Reuters said that the government also showed jurors numerous emails to and from Stanford authorizing transfers of money from a secret Swiss account. Former employees also testified that Stanford made all the key decisions.

Legal experts told Reuters that through the weight of its evidence, the government had set a high bar for Stanford’s defence team. ‘The defence has done a very good job of beating up Davis,’ said Wendell Odom, a criminal defence attorney based in Houston who has been monitoring the trial. But ‘it’s going to be difficult to prove that Stanford did not know what was going on,’ he said. Reuters said it is unclear if Stanford will testify. His legal team has said that he is not competent to aid his defence because of brain injuries from a jailhouse fight in 2009 and an addiction to anti-anxiety drugs. However, because the judge has ruled that Stanford is competent, the only way to reopen the issue would be for him to testify. Reuters said that such a move would be risky because it would give prosecutors a chance to question him. When they began their defence on Wednesday, Stanford’s attorneys gave the judge a list of 27 defence witnesses. Stanford was not among them, Reuters said.

From Friday’s hearing, the Associated Press related the views of some of the bilked investors. Retired IBM engineer Jim Eccles was eager to see the man accused of bilking thousands of investors in a $7 billion Ponzi scheme. Eccles, who lost his life savings, said he’d spent hours traveling on a bus for one reason.

“I wanted to see the guy that stole my money,” the 76-year-old Austin resident told AP, shortly before testimony resumed in the ongoing trial in Houston.

AP noted that three years have passed since Stanford’s business empire was dismantled in the hope that his companies, bank accounts and lavish assets could pay back the more than 21,000 people that prosecutors said were victimized. But so far, they’ve received nothing.

The recovery process has been complicated by conflicts in securing Stanford’s assets, which are spread across several countries, and a legal fight over whether some investors are entitled to a special fund that protects customers of failed brokerages.

According to AP, Paul Gallagher, from suburban Houston, said he lost $557,000 and now supports his 90-year-old mother-in-law, who lost $890,000. Gallagher, 64, said he still works as an engineering consultant and will “probably work forever now.”

For investors like Kate Freeman who live outside the U.S., their frustration is magnified. In a telephone interview from her home in Antigua, the British retiree told AP they feel “totally left out in the cold” when it comes to getting updates on the recovery process. She runs the Stanford International Victims Group.

“I live on charity. For somebody that’s never had to ask anyone for a penny, it’s very demeaning,” said Freeman, who is in her late 50s and lost $820,000.

AP said that as of the end of October, Ralph Janvey, the Dallas-based receiver, had collected nearly $217 million. Officials expect only about $500 million in assets will ultimately be recovered. This means investors would receive pennies on the dollar for their losses.

Bloomberg reported Wingfield as telling jurors she believed Stanford’s court- appointed receiver duplicated efforts and wasted money during the “chaotic” period after the businesses were seized by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission in February 2009.

Houston investor Cassie Wilkinson, 63, said in an interview with Bloomberg she lost $500,000 on Stanford CDs and has attended about 80 percent of the trial. A video shown to jurors yesterday, depicting a luxury Antigua resort Stanford was developing with investor money, was the toughest evidence she’s seen yet, she said.

‘Built Another Country’

“He took our money and built another country with it,” Wilkinson told Bloomberg during a break in testimony. “I was fighting back tears to see the lavish way he lived his life, and now we’re left to try to scrape through the rest of ours.”

Meanwhile, according to the Houston Chronicle, Wingfield described Stanford as both fixated on detail and distant, delegating more responsibilities to her and other lieutenants as his financial services empire grew.

“He was the type of person who had one main focus,” said Wingfield, a former vice president for Houston-based Stanford Financial Group. “Whatever was the pet project of the month, week, is what he would focus on.”

Wingfield worked as an assistant to Stanford and often acted as his delegate, traveling from Houston to Antigua, for example, to fix his money-bleeding newspaper, the Antigua Sun, or take a look at how to curb costs in other divisions, the Houston Chronicle reported.