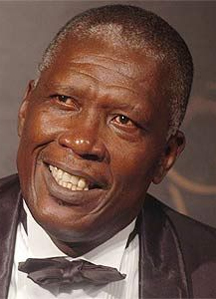

To the multitude of troubles that undermine West Indies cricket on an almost daily basis, Joel Garner highlighted another last week. It is the standard of umpiring.

Delivering his comments with the same devastating directness he did with the ball 30 years ago as the game’s tallest and most imposing fast bowler, the Barbados Cricket Association (BCA) president and West Indies Cricket Board (WICB) director said: “The time is right when we should get the people who cannot give good decisions out of the cricket.”

He was specifically against “a lot of ageing umpires who do not see very well and do not give proper decisions.”

This “plays on the confidence of the players” who, he said, are “not very comfortable when they see some umpires” officiating. It is a situation, he maintained, that leads to “bad cricket.”

It also brings on the unsavoury, orchestrated tantrums by players that have become common place following umpiring errors – or what, in the absence of the close scrutiny of television replays, are often no more than cons deserving of the referee’s attention.

Garner’s censure was prompted by what he termed some “funny decisions” that went against Barbados in their loss to Jamaica in the opening match of the season. Yet umpiring at regional level has been under the microscope for some time;

Garner noted that the WICB has been “talking about it” for the last three to four years. He made it plain as to where it should go next: “I think we’re going to come to that position where we’re going to have to take a stand in terms of who is sent out to do a job in the middle.”

Garner noted that the WICB has been “talking about it” for the last three to four years. He made it plain as to where it should go next: “I think we’re going to come to that position where we’re going to have to take a stand in terms of who is sent out to do a job in the middle.”

At present, the cricket umpires’ body in each territory submits two choices to the WICB to stand in regional matches, the relevant board two.

Aware of the need to search for, and groom, new recruits, the WICB, on the advice of its affiliate associations, has sought to introduce younger officials.

There is the feeling that, like the hierarchy of the WICB itself, umpires who hold positions in their domestic associations are not inclined to make way for others.

It is an unappreciated but, these days, not financially unrewarding job. The pay for each regional four-day match is US$1,000 and US$500 for a One-Day International with the prospect for the best to move onto the International Cricket Council (ICC) panel, with its annual contracts of US$100,000 and above, plus business class flights to wherever they are scheduled and accommodation in five-star hotels.

It is a path successfully taken to the ICC elite panel by Billy Doctrove whose 36 Tests since his first in 2000 have covered every Test-playing country. But the 57-year-old Dominican is the only West Indian at the highest level.

Significantly, the ICC has now replaced the West Indies four umpires at the lower level with younger men, all in their 40s. Joel Wilson and Peter Nero (on-field) have come in for Norman Malcolm and the late Clyde Duncan, Gregory Brathwaite and Nigel Duguid, third man, for Goaland Greaves and Clancy Mack.

Mack, 57, stood in his first regional first-class match as long ago as 1984; Malcolm, also 57, did his first 10 years later. Both remain on the regional panel for the current season, as do others if not as prominent. It is a situation that highlights Garner’s point.

It is not to say that the comparatively youthful umpires now being tried will develop into new Doctroves. Only regular assessments will tell. Quite apart from the comparative fame and fortune, their main motivation should be standards reached by those West Indians rated as among the best in their time.

The two most eminent are from the recent past.

Australia’s straight-talking captain Ian Chappell called Douglas Sang Hue, the little Chinese-Jamaican, the best in the game following their 1973 tour of the Caribbean. Others corroborated the assessment.

In the days before umps were debarred from standing in home series, Sang Hue did all five Tests in 1973 (Australia) and 1974 (England); he was the only foreigner chosen to officiate in Kerry Packer’s World Series Cricket. Now 80, his last international assignment was the 1981 Test against England at Sabina Park.

The most famous of all West Indian umpires was Steve Bucknor, the tall, slim Jamaican from Montego Bay. His 128 Tests and five consecutive World Cup finals are both records; his method of giving decisions with a nod of the head before the slow raising of the index finger were trademarks than earned him the nickname “Slow Death Bucknor”.

A fit 65, his knowledge is available as a mentor for his potential successors.

Like the game itself, umpiring has changed appreciably over the years. How much is evident in a story told by Learie Constantine in his book, “Cricketer’s Carnival”.

The highlight of regional cricket until the late 1930s was the inter-colonial tournament, involving Barbados, British Guiana (as it then was) and Trinidad and staged on rotation each year in the same territory.

Rivalry was so intense and public interest so passionate that Constantine said he knew of several players who “regularly carried revolvers” in case of “serious trouble”.

In the circumstances, the system of each team nominating its own umpire was bound to have sorry consequences. So it was in Georgetown in 1922.

“That night,” the Daily Chronicle reported, “an angry crowd collected about the Victoria Hotel, bent on rushing the car bringing the offending Trinidad umpire. Eventually, strong police patrols had to be requisitioned to clear the sidewalks and prevent what, at one time, looked like a rush at the hotel.”

Five times since, Tests (once a Packer SuperTest) have been interrupted following umpiring-induced riots – against England in 1954 at Bourda, 1960 at the Queen’s Park Oval and 1968 at Sabina Park, against Australia in 1978 at Sabina Park and the Packer match against Australia in 1978 at Kensington Oval.

With the dwindling crowds and the heavy security presence at all international matches, Garner should have no fears about a recurrence. Standards are what bother him.