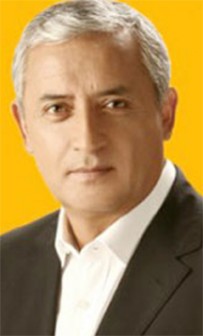

When I asked Guatemala’s new President Otto Perez Molina whether Central America is rapidly becoming a lawless place run by armed bands, much like Somalia, he shook his head and responded that any comparison with the African country is “exaggerated.”

Days earlier, on Feb 20, the Spanish daily El País had published an article by Salvadoran political analyst and former Marxist guerrilla leader Joaquin Villalobos, in which he has stated that Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras run a clear and present danger of becoming “a Latin American Somalia.”

Among his arguments: Honduras and El Salvador are already the world’s two most violent countries, with a murder rate of 81 and 66 people per 100,000 inhabitants a year, respectively, according to United Nations figures. Guatemala’s not too far behind with 41 homicides per 100,000 people.

Among his arguments: Honduras and El Salvador are already the world’s two most violent countries, with a murder rate of 81 and 66 people per 100,000 inhabitants a year, respectively, according to United Nations figures. Guatemala’s not too far behind with 41 homicides per 100,000 people.

By comparison, Mexico’s murder rate is of 18 people per 100,000 inhabitants, and that of the United States and most European countries is 5, or below.

“Central America is a compound of geological fault lines, drug trafficking routes, hurricane paths, historical grievances, insensitive oligarchies that resist paying taxes, irrational political polarization, states without natural resources, extreme poverty, high corruption rates, savage gangs, mighty drug kingpins, and a political class that is incapable of maintaining social cohesion,” Villalobos wrote.

Isn’t all of this true? I asked the Guatemalan President. Perez Molina conceded that some of these facts are undeniable, but added that he is confident that things will change for the better very soon.

He said that since he took office Jan 14, he has launched anti-crime and anti-poverty campaigns, and has started talks with colleagues in El Salvador and Honduras to jointly combat criminal organizations and gangs.

At the same time, he has launched a long-term regional campaign to decriminalize drugs and change the focus of the US-backed war on drugs to focus on education and reduction of drug use in consuming countries.

“It’s crazy to continue in the same path that we have been pursuing for the past thirty years,” Perez Molina told me. “We must find a new way.”

Regarding the region’s overall problems, he said, “All of these are serious, complicated problems that won’t be solved overnight. But I am confident that we will see signs of progress in 6 months, in one year.”

Some Central America watchers say they share Perez Molina’s optimism about the region. Manuel Orozco, a Central America expert with the Washington-based Inter American Dialogue think tank, says Central American economies have been growing slowly but consistently over the past two decades and are scheduled to grow by an average of 3.5 per cent this year. In addition, countries in the region have governments that, despite their problems, are functioning.

“Unlike in Somalia, in Central America you still have governments that have a monopoly of the use of force,” Orozco says. “They have been infiltrated by organized crime, but not taken over by it.”

Still, a United Nations International Narcotics Control Board (INCB) report released Tuesday says that violence in Central America has reached levels that are “alarming and without precedent.” It says that there are 900 maras — or criminal gangs — with more than 70,000 members in the five Central American countries.

And a survey released last week by the Chile-based Latinobarómetro polling firm shows that Central Americans have so little respect for police, that only 7 per cent of Hondurans and 11 per cent of Guatemalans and Salvadorans report crimes to police, a smaller percentage than in virtually all other Latin American countries.

My opinion: I don’t know whether Central America is about to become a Latin American Somalia, but Central American countries should do much more than they are doing to leave aside their petty internal disputes and drastically increase their security and intelligence cooperation. They should create, among other things, a regional anti-crime force.

As strange as it sounds, Central America’s tiny and poverty-ridden countries are still deeply distrustful of one another because of ancient territorial disputes that they are still keeping alive. Unless they create effective supra-national institutions, integrate their economies and forge regional anti-crime strategies, it’s hard to be optimistic about their future.

© The Miami Herald, 2012. Distributed by Knight Ridder/Tribune Media Services.