The sudden death of anyone in the prime of life is sad and shocking, more especially an international sportsman constantly in the public eye.

So it is with Runako Morton, a West Indies cricketer at various levels through all of his adult level, who died in a car crash in Trinidad on Sunday night, aged 33; so it was when Laurie Williams, a West Indies ODI player, perished in the same way in his native Jamaica in 2001, also aged 33, and when another Jamaican, Collie Smith, an all-rounder already rated one of cricket’s emerging greats at the age of 26, succumbed to injuries in a car accident in England in 1959.

The gloom that descended over the game, wherever it is played, was reflected yesterday in the immediate responses, through the internet’s several channels, of sorrowful teammates and one-time adversaries who knew him personally and of ordinary fans whose link was solely through his cricket.

The gloom that descended over the game, wherever it is played, was reflected yesterday in the immediate responses, through the internet’s several channels, of sorrowful teammates and one-time adversaries who knew him personally and of ordinary fans whose link was solely through his cricket.

From Nevis, which has rebutted its miniscule size to produce seven Test and ODI cricketers, Morton’s promise was initially recognized when picked for the West Indies under-19 in three matches against their Pakistani counterparts in the Caribbean in 1996.

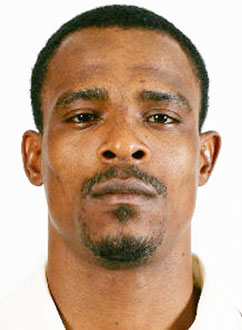

A strong, aggressive, almost entirely bottom-handed batsman, he proceeded to make heaps of runs for the Leeward Islands in the annual regional tournament (4,104 at an average of 44 with double hundreds in successive innings against Barbados and CCC in 2009 along with nine singles). But it was potential never fully fulfilled at the highest level, a failing of several others of the recent past.

The causes were a combination of problems of technique, the decline of the West Indies team itself and a volatile temperament that regularly led him into trouble. Yet his commitment and love of the game could not be queried.

The first of his run-ins with authority led to his expulsion from the West Indies Cricket Board’s Shell Academy, the first of its kind, in 2001. A year later, his fictitious claim of his grandmother’s death in Nevis so that he could exit the 2002 Champions Trophy early and indiscipline of an ‘A’ team tour of England, Ireland and Canada brought him a year-long ban.

There were later clashes with the law, the most recent a year ago when he and fellow Nevisian Tonito Willett were charged by the Trinidad & Tobago with possession of marijuana, an accusation to which they pleaded not guilty.

Reliable reports were that he had mellowed since marriage and a move three years ago to Trinidad. He piled up the runs in club cricket for Queen’s Park and became one of few players to represent two territories when picked for T&T in the 2011 regional first-class tournament.

The first of two strikes by senior players opened the way to his Test debut in Sri Lanka in 2005. Like many of the first-timers, he was embarrassed by the mesmerizing spin of Muttiah Muralither and and the swing of Chaminda Vaas. But his breath-taking catching in the slips moved Ian Chappell, commentating on the series, to rate him the best in the position at the time.

In 15 Tests between then and 2008, going in mostly at No.3 or No.4, he averaged just 22.03. The closest he came to a hundred was at Napier in 2006; unbeaten 70, he was denied the chance of the extra 30 runs by rain. His 67, against Australia at Sabina Park in 2008 in a fourth wicket partnership of 128 with Shivnarine Chanderpaul, was probably his best. The next Test was to be his last.

He was more at home in his 56 ODIs in which he averaged 33.75. Often opening with Chris Gayle, he hit hundreds against Zimbabwe and India but his unbeaten 90 in the West Indies victory over Australia in the 2006 Champions Trophy, adding 137 for the fourth wicket with Brian Lara, surpassed them for the aggression and grit that were the hallmarks of his cricket.

Yet it was in an ODI in Kuala Lumpur in 2006, also against Australia, that he struggled for 31 balls before he was out without scoring. It typified the contrasts that made him such an enigma.