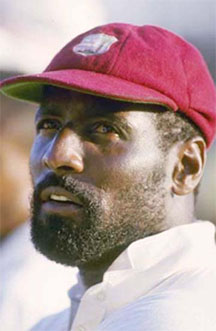

THE chiseled physique of the heavyweight champion who gave him the early nickname of “Smokin’ Joe” remained unmistakable. So was the self-confident swagger and the “Master Blaster” thwack of the stroke.

From half-mile away there could be no doubt that Isaac Vivian Alexander Richards (there was even a daunting ring to his full name, gradually and incongruously contracted to Viv) was still addressing his energy to a ball. Yet, when I last saw him in action last June during Pakistan’s tour of the West Indies, he was then in his 60th year and the sport that occupied his attention that day was not that on which his formidable reputation is made.

If golf at the Cedar Valley course in his native Antigua has become an almost daily hobby rather than the mission that was his cricket, those who play with him report there is the same competitive intensity as he aims to drag his handicap down to scratch. They still speak of the withering stare of annoyance that made him the most intimidating player of his generation, perhaps of any generation

Now Sir Viv and a National Hero after honours from his grateful government, he is as relaxed among old friends, as he is in his official capacity as ambassador, promoting Antigua and Barbuda as a holiday destination and an investment opportunity, and in heading a campaign for responsible drinking for Johnnie Walker whisky.

Sadly, in these deeply depressing days for West Indies cricket, his passion has been diminished as administrators, players and, now inevitably, the several governments unashamedly and destructively fight for its control.

Sadly, in these deeply depressing days for West Indies cricket, his passion has been diminished as administrators, players and, now inevitably, the several governments unashamedly and destructively fight for its control.

Nostalgia, fueled by recollections in the media and in documentaries such as the recent “Fire in Babylon”, has become the convenient salve for those who yearn for a return to earlier, happier days that were driven by a host of exceptional players and, in the case of Frank Worrell and Clive Lloyd, outstanding leaders. Twenty-one years after he played the last of his 121 Tests, Richards is its focal point for it was his overwhelming self-belief and enthusiasm that most epitomized West Indies’ excellence in their decade of dominance in the 1980s.

As he marks his 60th birthday today (Wednesday, March 7), the presence in Antigua of a host of the past greats, from generations before, during and after his, for the special, week-long celebrations is a tribute to the esteem in which he is held.

Described by Lloyd during his heyday as “an integrated West Indian, an excellent example of the role that cricket plays in promoting regional participation at the expense of regional isolation”, his name and others of his rank should be to the forefront in seeking to revive the game he ruled for so long. Instead, the majority of those in positions of leadership while West Indies cricket has been brought to its knees lack cricketing pedigree.

Richards once attributed the West Indies’ prolonged success in his time to team unity and pride, two attributes glaringly absent since. According to him, the teams in which he featured were “like a band of brothers coming together at a time when the Caribbean needed some upliftment, needed some folks to feel pretty proud about”.

No one fit the bill better than Richards himself.

From the start, his passion was fired by the bias that kept the smaller islands, such as Antigua, out of the mainstream of West Indies cricket until 1966. It denied his father, Malcolm, a fine fast bowler, even the chance of Test cricket. When Viv joined Andy Roberts in 1974 as the second Test player from among the island’s 70,000 population, he was determined to right the wrong and was equipped with the requisite physical and mental strength, talent and attitude to ensure that he did.

David Gower noted another, perhaps even stronger motivation. He was “a black man proving that race and skin colour count for nothing in terms of genuine sporting competition”. If Gower sensed it, it was even clearer to black men everywhere.

They were powerful dynamics that Richards carried with him every time he entered the fray. The stronger the bowling, the bigger the event, the more he reveled in the challenge. To back down would be a betrayal of everything he stood for. To accentuate the point, he refused to seek the protection of a helmet, defying the army of bowlers seeking to knock his block off.

Like all true champions, he often kept his best for the grand occasion.

In the West Indies’ triumph in the first World Cup final at Lord’s, his swooping fielding and pin-point throwing ambushed three Australians, among them the dangerous Chappell brothers.

In the second World Cup final, his Man of the Match, unbeaten 138 so unnerved England that the 92-runs victory was the certain consequence.

He marked the inaugural Test on home turf with his wedding two days earlier and an inevitable hundred against England at the Antigua Recreation Ground, the ARG, where he first revealed his rare skills as a boy.

Five years later, he reeled off Test cricket’s fastest 100, off 56 balls, in what was his first Test at the ARG as West Indies captain. The opponents were again England for whom he seemed to specifically reserve something exceptional. There were 35 hundreds in all, 24 in Tests, 11 in ODIS. All bore the unmistakable stamp of Richards’ supremacy. For me, the most special was his first, 192 not out against India at Delhi in his second Test. It was immediate evidence of the Richards the cricket world would come to know and admire.

Baffled by Chandrasekhar in the first Test, he twice fell cheaply to the leg-spinner (he still made a mark with two breathtaking catches at short-leg). Two weeks later, Chandra was absent with an injury. The potent spin trio of Bedi, Prasanna and Venkataraghavan remained but it was the cue for Richards to smash six sixes and 20 fours on his way to his big maiden hundred. It was the sign of things to come.

By the time Lloyd retired in 1985 and the captaincy passed to him, the team was beginning to fragment. It became increasingly difficult to maintain the unbeaten streak yet it was still intact by the time he bowed out after the series in England in 1991, aged 39. Even then, he could see problems ahead. West Indies cricket had become “too much of a cat-and mouse type of game”, he told me at the time. There was “a lot of jealousy around, a lot that is not genuine”.

Insularity was again to the fore and there was no longer “that sense of unity and loyalty among our people of getting behind the team and supporting it right to the end”.

Such talk might have been dismissed as bitterness by the powers that were. Instead, it proved a forewarning of the ever increasing troubles to follow. Nor did Richards find much comfort when he became involved again a decade after his retirement.

His stints as coach and chief selector were short-lived. The West Indies Players Association (WIPA) complained to the West Indies Cricket Board (WICB) that he and other selectors “verbally belittled and threatened” some of its members in public. It reflected his frustrations at the way West Indies was going and the sensitivities of players who did not appreciate what it took to create West Indies cricket’s enviable legacy.

Nothing infuriated him more than the shambles that led to the abandonment of the 2009 Test against England at the impressive new stadium in Antigua named in his honour and the failure of anyone from the WICB to accept responsibility or even to apologise to its embarrassed public.

Except for a stint as one of Allen Stanford’s “legends” in the disgraced Texan’s ill-starred Twenty20 venture and the rare comment on a particular issue, Richards has stayed clear of the “cat-and-mouse type of game” West Indies cricket has become.

His sporting enjoyment now comes from a game involving a smaller ball in which he is his own opponent.

Like so many of those who have built on the cherished legacy of West Indies cricket, he has been marginalized. Still, there are the present birthday celebrations and all that footage of his finest deeds to stir emotions and raise hopes that it just might inspire the present generation into an overdue revival.