Professor Neil Lancelot Whitehead, 3/19/56 – 3/22/2012- born Harrow, London died peacefully surrounded by family in Madison, Wisconsin – he was 56 years old. Educated in Philosophy, Psychology and Anthropology at Oxford, he took his D. Phil in 1984 in Anthropology. He was a devoted advocate of the Guyanese peoples and most especially the Amerindians of Guyana, whom he deeply respected. He dedicated his scholarly career to the interests and promotion of Amerindian peoples across Amazonia through his work on the history of peoples in lowland South America, tirelessly proving and underscoring their validity, their heritage, their rights to respect and their agency. In many ways a true voice of Guyana, for the people, to many parts of the world, his legacy can be perpetuated through following his example of fierce inquiry sometimes at a cost to the self and a generous scholarship meant to be shared with the rest of humankind. Dr. Whitehead was ill with a rare form of renal cancer, which was not curable. He lived the last few months of his life in the same pursuit of knowledge, experience and justice although his energies were ebbing. He was and will continue to be a prolific published scholar, with several works forthcoming within 2012 alone. His love for Guyana and the Guyanese people was lifelong and intense. His passing allowed him to be free of his tired body and roam free over the landscapes he admired, the rolling Pakaraimas and deep forest creeks and pathways of Guyana’s interior. If you have any remembrance of Neil, please share it with someone today in commemoration. May he be fulfilled in whatever he pursues in the next life…..

(From Stephanie Aleman. In the weeks to come, Stephanie and Terrence Roopnaraine will, in this column, offer words for Neil).

The dismissal of University of Guyana lecturer Freddie Kissoon earlier this year, triggered a series of actions that brought the ongoing crisis at the University of Guyana – the debilitating result of decades of politicization of the Council – to public attention. Since then, committed staff, students and faculty have launched Operation Rescue UG. An online petition calling for the replacement of non-academic members of the governing council, will I believe be submitted to all political parties this week. The urgency of this matter should not be underestimated, as the term of the current Council expires next Monday March 30th.

This column is written as a tribute to those who are standing their ground at the University of Guyana, and shares with the last two diaspora columns authored by Rory Fraser, the sense of hope, excitement and possibility for new beginnings.

This column is written as a tribute to those who are standing their ground at the University of Guyana, and shares with the last two diaspora columns authored by Rory Fraser, the sense of hope, excitement and possibility for new beginnings.

It has taken me longer than usual to write this column because I was trying to craft rational arguments about the importance of academic freedom and resources (which I believe in fully, don’t get me wrong), and finding myself turning to our poets and novelists to help me ‘language’ what I really wanted to say.

The crisis at UG is symptomatic of something gone terribly wrong.

We are awash in mediocrity, and I am not measuring it in terms of an obsession with qualifications (the farmer in a flooded village can tell us way more how to protect our fragile coast than the best paid consultant flown in to the country for the first time). No. What I mean is something deeper, a spiritual and psychic crisis that comes from participating in a system that bows down to petty power, that fears the uninhibited joy, endless curiosity and relentless inquiry that children display best and that we need in our everyday encounters with each other, because of the beauty and boundless horizons of political possibility that they manifest. This mediocrity, which has become our normal, is not all that we can or should aspire to, because it subscribes to the narrowest and most deforming notions of power. Power that rewards a few, that comes at the expense of others, that requires you always to have your foot on someone else’s neck.

I forget who it was (perhaps Frantz Fanon, but certainly inspired by him) that memorably said that at independence what we had in colonized countries the world over was an ex-change but not a real change. And in Guyana we might say that not just in relation to 1966, but 1992, though we thought differently at the time.

This point is captured near the beginning of the novel, Season of Adventure by Barbadian George Lamming, in the dialogue between two of the book’s characters, Crim and Powell:

Crim, “Is like how education wipe out everythin’…everythin’ wipe out, leavin’ only what they learn…I was thinkin’…how the Independence would change all that wipin’ out, change everythin’ that confuse.’

Powell answers angrily, “What change that can change? Might as well call your dog a cat an’ hope to hear him mew. Is only words an’ names what don’ signify nothin’.”

In other words, we talk about independence, we talk about ‘free and fair elections’ since 1992, but all this surface talk masks how little has changed. In response to Crim’s suggestion that the colonizers (or their inheritors, our political classes today) have given us our freedom, Powell goes on: ‘It don have that kind o givin…is wrong to say that, ‘cause free is free an’ it don’t have no givin.’ Free is how you is from the start, an’ when it look different you got to move, just move, an’ when you movin’ say that is a natural freedom make you move. You can’t move to freedom…’cause freedom is what you is, an’ where you start an’ where you always got to stand…free is free, an’ it don’t have givin’ an’ it don’t have takin’…if ever I give you freedom…then all your future is mine, ‘cause whatever you do in freedom name is what I make happen. Seein’ that way is a blindness from the start.”

In other words, we talk about independence, we talk about ‘free and fair elections’ since 1992, but all this surface talk masks how little has changed. In response to Crim’s suggestion that the colonizers (or their inheritors, our political classes today) have given us our freedom, Powell goes on: ‘It don have that kind o givin…is wrong to say that, ‘cause free is free an’ it don’t have no givin.’ Free is how you is from the start, an’ when it look different you got to move, just move, an’ when you movin’ say that is a natural freedom make you move. You can’t move to freedom…’cause freedom is what you is, an’ where you start an’ where you always got to stand…free is free, an’ it don’t have givin’ an’ it don’t have takin’…if ever I give you freedom…then all your future is mine, ‘cause whatever you do in freedom name is what I make happen. Seein’ that way is a blindness from the start.”

I am reminded of this passage when I see Ministers of Government and other appointed apostles taking to the letters section of the daily newspapers to admonish, single out and discipline individuals and organizations because they have broken the rules (whose rules and whose interests do they serve?), or because they have lost their principles (because they dare to disagree with official positions and actions), or because they bite the hand that feeds them (as if the money the hand disburses belongs to those who now run things and not to the taxpayers who are all Guyanese).

Martin Carter explains this beautifully in a commencement address he gave in 1974, at the Eighth Convocation ceremony of the University of Guyana (I urge my colleagues to get hold of it, make it compulsory reading and discussion for everyone, especially now).

Carter opened his address by telling the audience of an aquatic creature native to Mexico, the AXOLOTL, which reaches sexual maturity in larval form and never goes on to transform into adult form (which is terrestrial) because the particular gland that would enable this change is suppressed. For Carter, we resembled AXOLOTL (it is sobering, really, to recognise with a jolt that he could have said the same words today to Guyanese, nearly forty years later):

“The truth is that every society is made of conflicting interests: the interests of the rulers and the interests of the ruled; competition within the ranks of the rulers and competition within the ranks of the ruled; and it is from the creative encounter of these interests, from the clash of all these forces that a valid hierarchy of values emerges to challenge the very premises that sponsored them. Nor can this encounter be abolished. It may be obscured and take perverse forms of expression, in which eventually the individual personality suffers erosion and ceases to function in a creative way, until, inevitably, general paralysis of the spirit overcomes. This is the war we have to fight, the war against paralysis of the spirit, for I am tempted to think in a metaphorical way, that just as the suppression of the thyroid gland in the AXOLOTL, could have halted that creature’s metamorphosis, just so this paralysis of spirit if not itself overcome, can delay, if not corrupt, our transformation into a free community of valid persons. Greater and greater daily seems to grow this paralysis as the individual person is confronted with the sometimes inscrutable workings of political and bureaucratic power…”

This is what makes Operation Rescue UG so potentially significant. We have to hold on to hope to defeat mediocrity, to struggle every day against the paralysis of the spirit, and to believe that we are poised on the cusp of something that has the potential to lift us all.

But Crim’s observation that education wiped out everything except for what people learned, is also a crucial one as we contemplate the foundations of this work being done. It is bigger than the technical reports and the funding and the equipping of labs and classrooms. All these matter, but there is more at stake, and it has to do with fashioning ourselves as a free community of valid persons, to work for change and not for an ex-change.

In his 1974 address, Martin Carter cautions that a necessary emphasis on systems or institutions should not supplant or perhaps even precede an engagement with “informal social and psychological elements, elements that defy codification, like commitment to the name but not the substance of some one or other political ideology; or the prejudices associated with skin colour; or the failure of communication that accompanies racial cleavage; or, most important of all, the exercise of state power which brooks little interference and distorts men and laws in the overt and covert processes of its consolidation and hegemony. It is the action of these informal elements in their many combinations, which can and does bring about the perversion of creative strategies and exacerbates those very ills these strategies were originally planned to control.”

As the process unfolds, it provides an opportunity to think deeply and carefully about the way the University is positioned – and sees itself – in relation to communities of knowledge practitioners outside its gates. Caribbean-American feminist and poet Audre Lorde once said, “Some women wait for something to change and nothing does change. So they change themselves.” This is not simply or even about UG leading by example, but about looking elsewhere for how example is being multiplied. In the last weeks alone there have been so many signs: the letter from Help and Shelter stating that because a group gets government funding should not mean that one has “no right to criticize or question the government when we see gaps or deficiencies in areas that fall within our mandate”; the letter by UG lecturer C.R. Bernard insisting on his right to state his opinion without being placed into some racial or political box; the statement by the Society Against Sexual Orientation Discrimination questioning the government’s sincerity in relation to a recent announcement that it will be running a public consultation on repealing anti-gay laws; the courageous public statement from Assistant Police Commission-er David Ramnarine on the allocation of the $90M election fund; the picketing of parliament by Red Thread activists. In other words, the staff, faculty and students at the University of Guyana are not alone, once we open our senses to the motion around us. This is what solidarity looks like, and connecting the dots, seeing the links, forging the relations, is also part of the work.

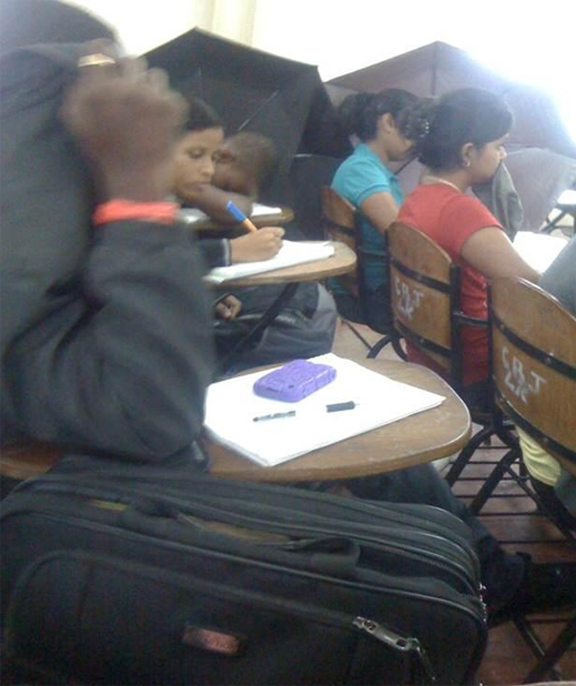

Over the weekend someone sent me a shocking image that had been posted on facebook by UG students, of students in a lecture theatre taking notes with one hand while balancing an umbrella against the rain in the other because the roofs were in such disrepair. I asked myself how much had changed from the mid 1980s when I attended UG amidst broken down classrooms and toilets, lecturers moonlighting as taxi drivers and market vendors, people missing classes and work to sit in gas lines for hours and even days? But Martin Carter reminds us that in situations of such deprivation, “such concern can be manipulated and used, if not to justify, then at least to conceal transgression. On the other hand, it is precisely in times of crisis that we must re-examine our lives and bring to that re-examination contempt for the trivial, and respect of the riskers who go forward boldly to participate in the building of a free community of valid persons.”

A salute to our friends at the University of Guyana for what they are working towards, a tomorrow that belongs to all of us.