Mario is a pimp and a heroin addict in Rome. He regularly pays graft. While Mario’s services and his consumption and production are illegal, they are nonetheless marketed. Money changes hands. Mario’s activities are part of Italy’s hidden economy. In a nation’s bookkeeping, not all transactions are accounted for, but at the end of any year, it’s impossible to measure the black market. So many nations, including Italy, regularly impute the minimal value for the hidden economy in their national accounts. So Mario’s illegal services and production and consumption activities are recognised and recorded as work. That’s what the International Economic System says.

“Now Consider Tendai, a young girl in the Lowveld in Zimbabwe. Her day starts at 4.00 am when, to fetch water, she carries a 30-litre tin to a borehole about 11 kilometres from her home. She walks barefoot and is home by 9.00 am. She eats a little and proceeds to fetch firewood until midday. She cleans the utensils from the family’s morning meal and sits preparing a lunch of sadsa for the family. After lunch and the cleaning of the dishes, she walks in the hot sun until early evening, fetching wild vegetables for supper before making the evening trip for water. Her day ends at 9.00 pm after she’s prepared supper and put her younger brothers and sisters to sleep. Tendai is considered unproductive, unoccupied and economically inactive. According to the International Economic System, Tendai does not work and is not part of the labour force.”

The above are two typical examples found in gender literature to provide a graphic picture of how paid and unpaid, useful and antisocial work are treated in national accounts. But they are only two dimensions of the broader problem of gender and other biases associated with national resource allocations. On the face of it, in relation to gender, budgets may appear neutral instruments, but that they are not. For example, increased spending on water, child-care, education, health, unemployment benefits and pensions can reduce the burden of household work and free more women to engage in paid employment and this can lead not only to increased family incomes, women’s empowerment and more expenditure on children and their education but also to increases in general economic growth. So our general societal commitment to gender equity requires that since expenditures have different impacts on different sectors of the society including women and men, efforts be made to more efficaciously construct our reality.

The above are two typical examples found in gender literature to provide a graphic picture of how paid and unpaid, useful and antisocial work are treated in national accounts. But they are only two dimensions of the broader problem of gender and other biases associated with national resource allocations. On the face of it, in relation to gender, budgets may appear neutral instruments, but that they are not. For example, increased spending on water, child-care, education, health, unemployment benefits and pensions can reduce the burden of household work and free more women to engage in paid employment and this can lead not only to increased family incomes, women’s empowerment and more expenditure on children and their education but also to increases in general economic growth. So our general societal commitment to gender equity requires that since expenditures have different impacts on different sectors of the society including women and men, efforts be made to more efficaciously construct our reality.

Red Thread has been mounting a picketing exercise on the national assembly intended to raise awareness of the plight of women and particularly poor women. They have been calling on the parliament but particularly women MPs to pay more attention to and be more proactive in protecting the rights of women as the budget looms. This is admirable and here I seek to add to the discourse by bringing to the attention of the government, parliament and the nation that it is both possible and necessary for us to pay more attention to gender when planning and executing budget provisions.

Lest it be mistaken, gender-sensitive budgeting does not mean one budget for men and another for women. Indeed, the concept seeks “to ensure that budgets and economic policies address the needs of women and men, girls and boys of different backgrounds equitably, and attempts to close any social and economic gaps that exist between them … ensures allocation of adequate funds for achieving gender equality commitments and aids in avoiding a negative impact on women by assessing the impact of budgets on gender relations. Therefore, budget allocations by Government should be carefully determined and monitored.” (See “Parliament the Budget and Gender” 2004 Handbook of the Inter-Parliamentary Union, for a comprehensive discourse). The emphasis however tends to be upon women and girls, largely because they are usually more disadvantaged in the gender balance.

Lest it be mistaken, gender-sensitive budgeting does not mean one budget for men and another for women. Indeed, the concept seeks “to ensure that budgets and economic policies address the needs of women and men, girls and boys of different backgrounds equitably, and attempts to close any social and economic gaps that exist between them … ensures allocation of adequate funds for achieving gender equality commitments and aids in avoiding a negative impact on women by assessing the impact of budgets on gender relations. Therefore, budget allocations by Government should be carefully determined and monitored.” (See “Parliament the Budget and Gender” 2004 Handbook of the Inter-Parliamentary Union, for a comprehensive discourse). The emphasis however tends to be upon women and girls, largely because they are usually more disadvantaged in the gender balance.

Like most commitments to social equality, the obligation to gender-sensitive budgeting can remain insubstantial if stakeholders are not aware of the gravamen of the problems and the scope of their commitments. Gender budgeting is said to have begun in Australia but was abandoned at the federal level there in 1996. Over the years since then, more than fifty countries, some in our own region (Brazil, Chile, Peru and Bolivia), have attempted them. However, a UNIFEM review in 2003 identified only about twenty countries with ongoing programmes and South Africa’s is said to have one of the best documented budget-sensitive approaches which assesses the impact of both national and local budgets on women. The strong alliance between civil society and government departments is said to be one of the more important features of the South African approach.

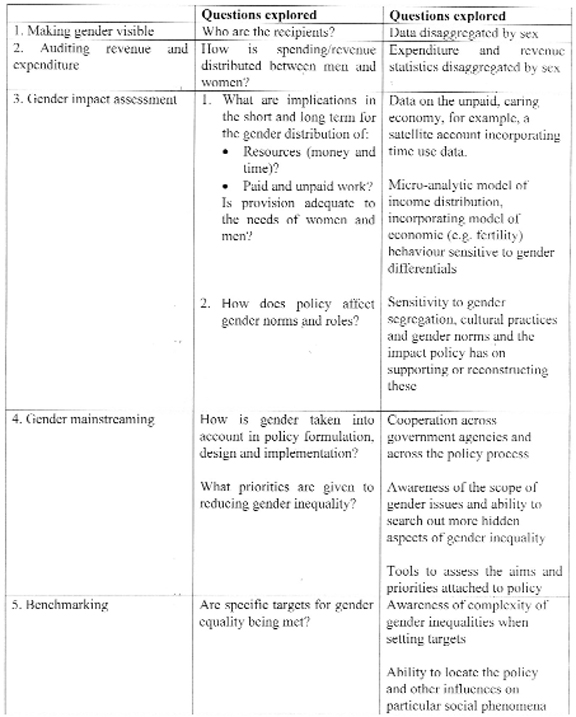

The following basic outline should serve to indicate what is involved in a comprehensive approach to gender-sensitive budgeting.

Gender-sensitive analysis in the UK budgetary process

The above model indicates that establishing a comprehensive gender-sensitive approach to budgeting would be complex and taxing for a decrepit bureaucracy such as ours. However, I believe that, even if they will bicker – as is normal and useful – about specific policy responses, this is one area in which the government and opposition could make a general commitment and a start. Of course, meaningful stakeholder participation in the process of budget formulation and monitoring is a sine qua non for the success of gender- sensitive budgeting.